17.1. Newton’s First Law#

Sustain constant speed with Newton’s first law

| Author: | Peter Dekkers |

| Time: | 15-45 minutes |

| Age group: | 25 - 16 |

| Concepts: | Force, speed, acceleration, Newton’s first lawS |

Introduction#

In their own practical work students may easily overlook the details in the phenomena. This demonstration on Newton’s First Law is meant to direct their thoughts and observations to such details. Invite students to express their expectations and predictions, compare these amongst each other and then test them in observations. This is meant to help you direct how students adjust and shape their concepts and beliefs in the context of Newton’s First Law. Differently from most demonstrations of Newton’s First Law, no attempt is made to reduce friction to zero. It is merely made negligible.

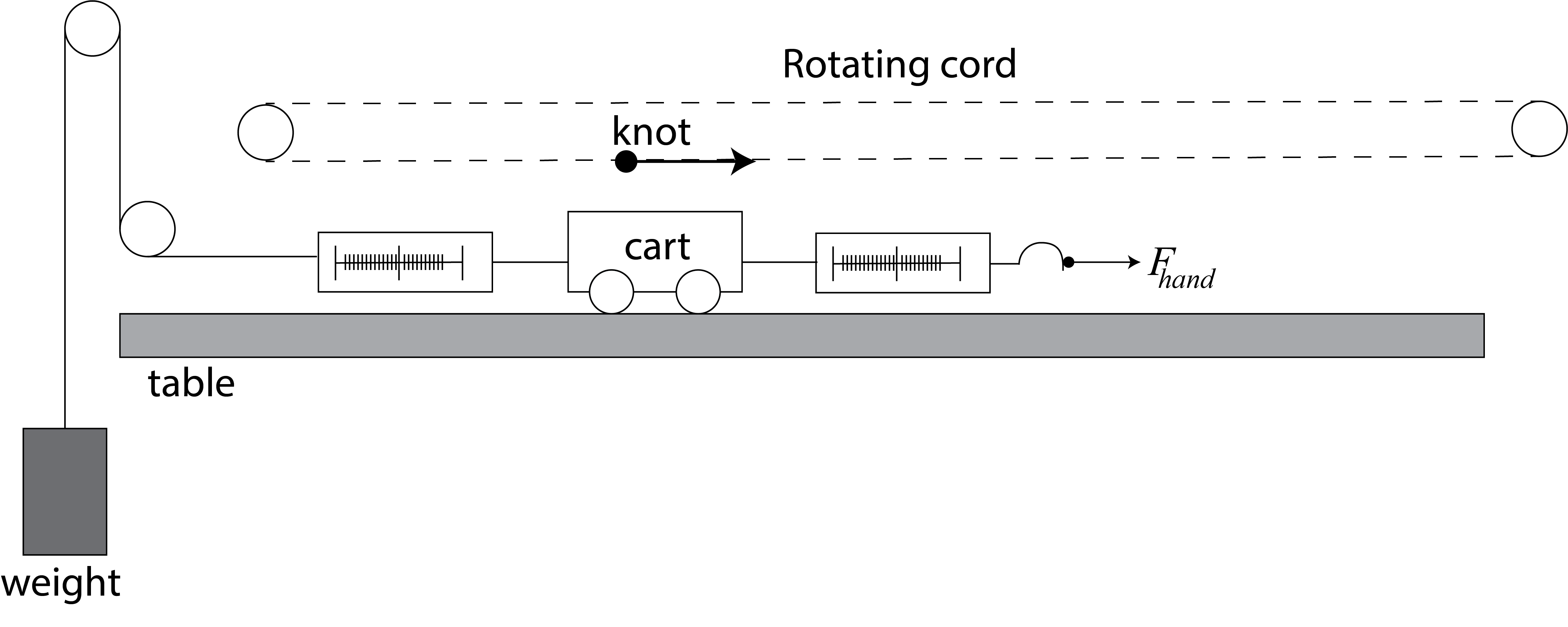

Fig. 17.1 A schematic of the experimental setup#

Equipment#

A smooth, flat table that is as long as possible

A retort stand that is as high as possible, with clamps and two pulleys

A hanger with slotted masses

A thin cord that is twice as long as the table

Two spring-balances

A cart

Power source and electromotor

Two more retort stands each with a clamp and a pulley

Preparation#

Build the set-up, see Figure 17.1. Pull the cart toward the right by hand. A mass, attached to the cart by a cord running along pulleys, creates an opposing force. The table is as long as possible, the top pulley is positioned as high as possible, so as to create a long runway. An electric motor (not shown) propels the revolving cord. Select slotted masses and matching spring-balance so that friction is negligible up to speeds of about 1 m/s.

Procedure#

The cord, with a knot in it, is revolving uniformly (at constant speed). If you pull the cart with your hand along with the knot, the cart has the same constant speed as the knot. Note that it takes a moment to attain that speed, but then the spring-balances can be read. The following questions can now be raised and are meant to be answered in the demonstration that follows:

How does the pulling force compare to the opposing force, during the part of movement where the speed is constant?

What changes if we select a greater constant speed?

A Predict-Observe-Explain approach is appropriate here. An example is presented in this worksheet. Students do predictions by writing up the answers they think will be found to the two questions above. Then the experiment is carried out. A somewhat larger speed is realized by (slightly) increasing the voltage across the electric motor. A conclusion is formulated on the basis of the observations. The worksheet questions direct students to apply the gained knowledge in similar contexts, with the goal of exploring whether Newton’s first law is generally applicable.

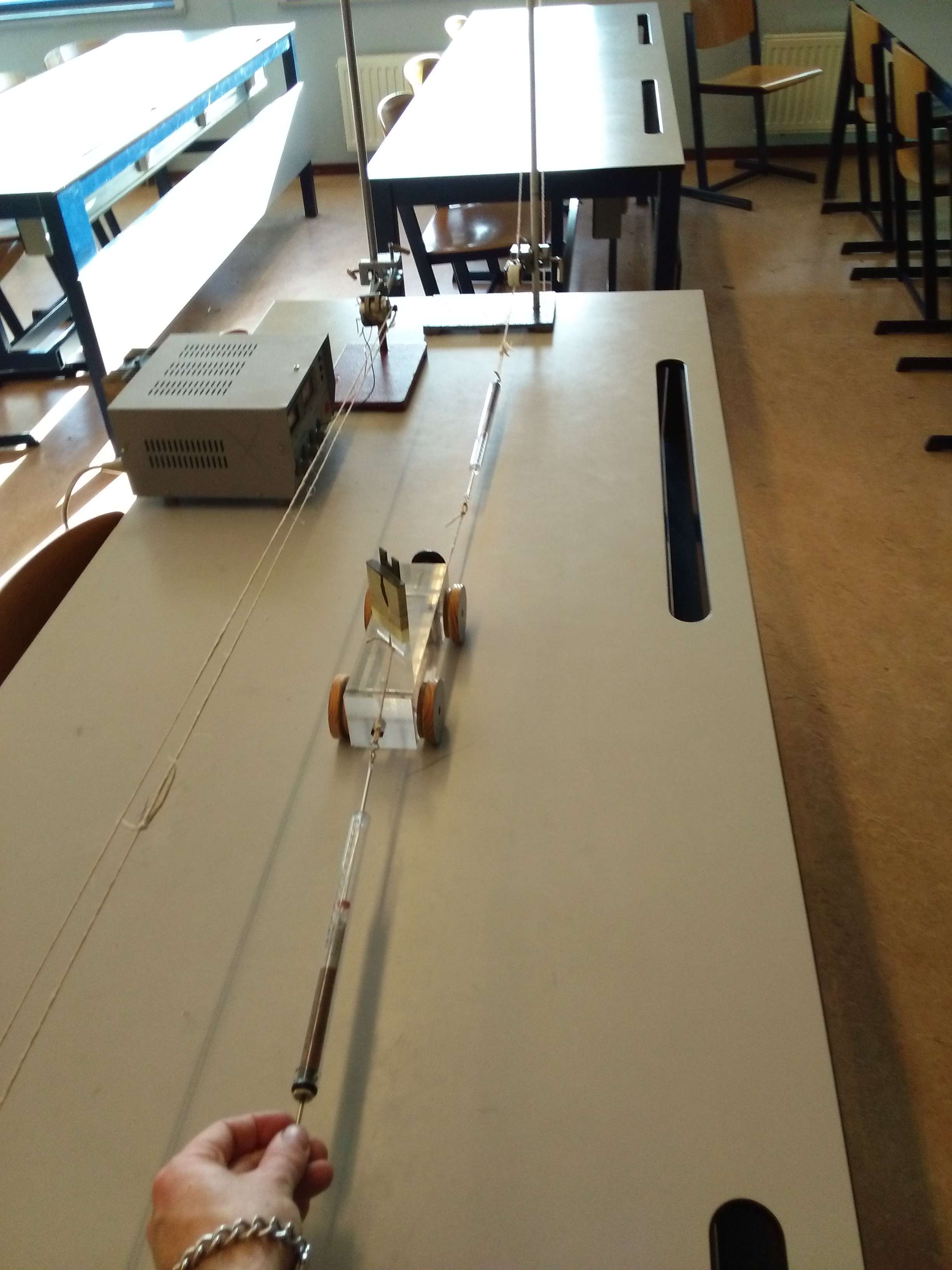

Fig. 17.2 The actual setup#

Physics background#

If an object moves at constant speed, the propelling and counteracting forces are equal, irrespective of the speed of the object. Furthermore, maintaining a larger speed does not require a larger propelling force, if friction is negligible. To maintain the speed, it is enough for propelling force and counteracting force to be equal in size. All of the forces measured in this set-up, if it functions properly, will be of the same value (equal to the weight of the hanging mass), independently of speed and direction. It is sometimes claimed that Newton’s First Law can be verified only in these idealized, frictionless circumstances. But here we see that also in ordinary situations, the net force is zero if the velocity is constant.

Tip

Teachers sometimes tend to omit the revolving cord, but then how do you know or verify that the speed is constant?

The electric motor might be attached directly to the cart, to pull it along. However, especially if you involve students in carrying out the measurements, there is added value in students feeling directly that maintaining a higher speed does not require a greater pull.

The pulling force and counteracting forces must act at the same height on the cart, or torque may affect and disturb the measurements. If during testing the forward force turns out to be greater than the opposing force, check if the pulling cord did not fall off a pulley. If not, increase the hanging mass. Using about 0.3 kg is normally enough to make friction negligible.

It is not so easy to maintain a constant speed, practice a few times before measuring. In a prototype version of the demonstration, studying the at-rest situation was included. This turned out to be (1) distracting, because friction can no longer be neglected, and (2) unnecessary, because students are well aware that the forces should be equal in that case.

Follow-up#

Students often start raising objections after a short while: “Yes but, surely the forces are not equal at the beginning, when the cart starts to move?” Be alert to note and respond to these remarks, because this is precisely where students’ views do accord with Newton’s. From a science educational perspective, our aim is that students come to distinguish conceptually between situations where the cart is accelerating, and those where the speed is constant. Rather than exposing ‘misconceptions’, pay a great deal of attention to this conceptual differentiation, especially when students themselves express it. Encourage the idea that physics does accord with what they already know about motion and its causes. But expresses that knowledge more precisely and accurately.

Obviously, a single experiment will not cause students to expand and differentiate their understandings of force and motion to become fully Newtonian. Many students will still speak of the ‘force of motion’ when they explain why a skater or cyclist keep on moving beyond the finish line, after they stop propelling themselves. In developing Newtonian descriptions and explanations, students need to know when and why something is called a force in physics, and develop the concept of ‘interaction’ and distinguish force from momentum (Dekkers and Thijs [1998]).

References#

Peter Dekkers and Gerard Thijs. Making productive use of students' initial conceptions in developing the concept of force. Science education, 82(1):31–51, 1998.