13.4. Cylinder Puzzle#

Exploring the Nature of Science

| Author: | Peter Dekkers |

| Time: | 15-30 minutes |

| Age group: | 14 - 18 |

| Concepts: | Nature of Science |

Introduction#

This activity involves no physics but demonstrates a model of how physicists (and other scientists) work and what they try to achieve. Students take on the role of scientists to describe and explain confusing and astonishing observations. Then, they reflect on them.

This demonstration is described earlier in .

Equipment#

Opaque cylinder with opaque lids on both sides;

about 50 cm of sturdy rope or cord.

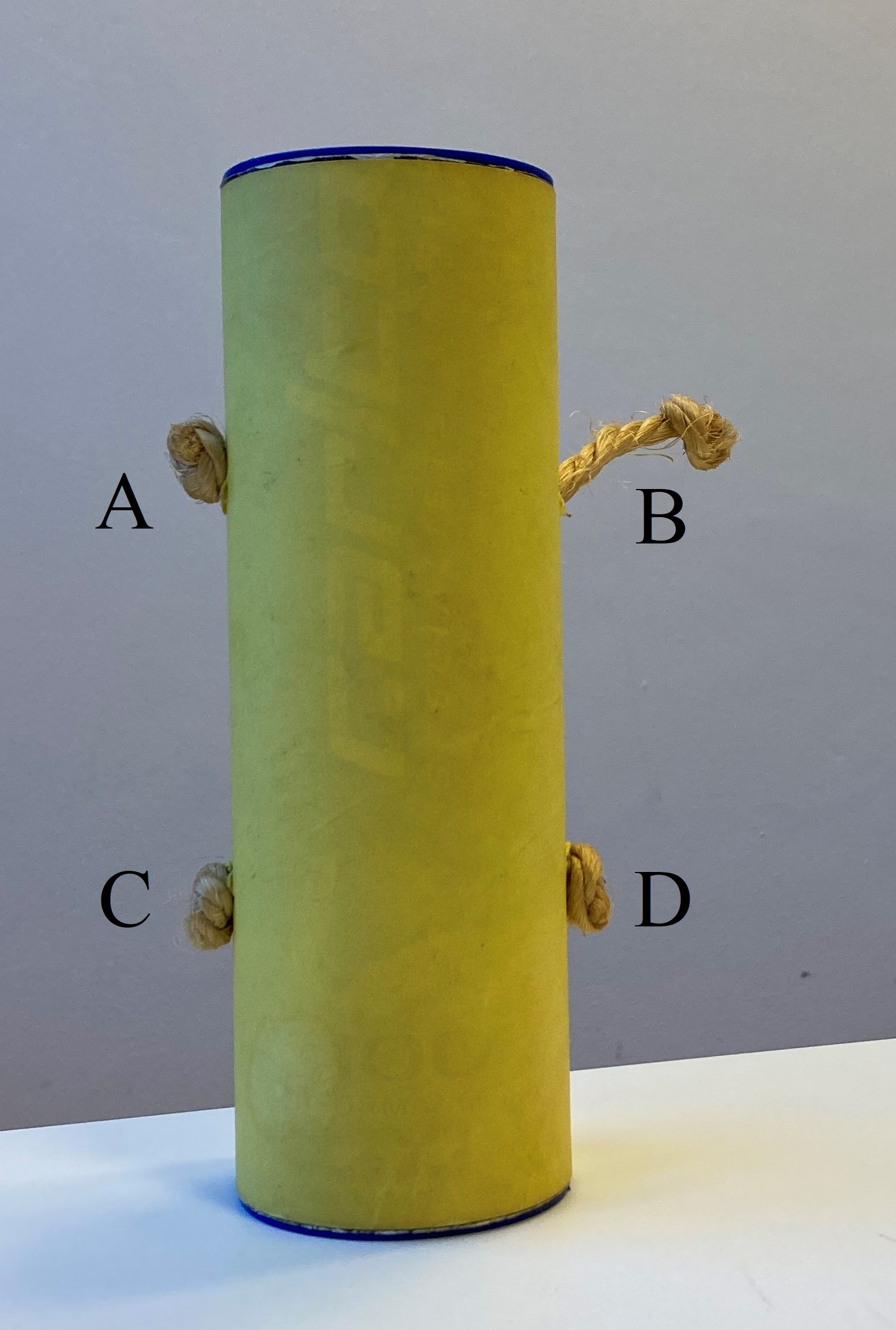

Fig. 13.8 The cylinder puzzle - A model of the universe#

Preparation#

Make four holes in the cylinder. Use two pieces of cord, thread them through the holes, with one passing over the other inside the cylinder, for example as shown at the top left of Figure 13.9. Adjust them: both strings should loosely fit inside the cylinder. Tie knots at the ends and cut to size. Then, pull on one of the knots: this should result in something like Figure 13.8. Each time a knot is pulled, a few centimeters of rope should come out there, while the protruding piece is pulled inward.

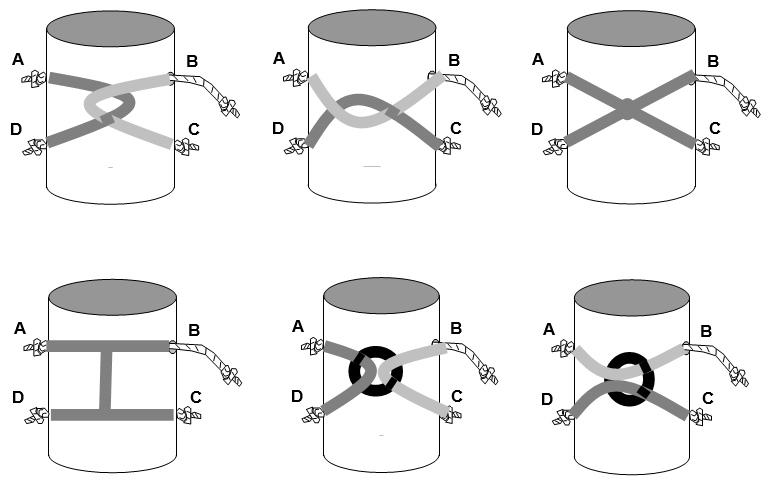

Fig. 13.9 All these models of the contents of the cylinder are consistent with all observations.#

Procedure#

Explain that the cylinder you have is a model of the universe in tha sense that it can help you to understand how scientists study that universe. Studying this universe in a scientific manner is what this activity is about. So, observing carefully what happens is important! Next pull on three knots successively with a short, firm tug, for example, A-B-D-B. Repeat it a few times. Also, try A-D-B-D-A-B. For now leave knot C alone. Meanwhile students carry out the following tasks and answer these questions:

Observing and recording. Carefully and systematically document your observations.

Explaining. What do you think is inside the cylinder and can explain that the strings behave as we have seen? Give a possible explanation, use a sketch. An explanation that could be correct but still needs testing is called a hypothesis.

Predicting. What do you think will happen if knot C is pulled? Collect predictions. Then, pull knot C. You may want students to compare their drawings of what may be inside the cylinder. Students may suggest further actions to explore and test their hypotheses; carry these out unless they involve opening the cylinder. They may adjust their hypotheses to match the new observations.

Comparing answers. Discuss the results together.

Did you manage to come up with a good explanation? Why do you believe it to be good?

‘Good’ explanations match the observations, and with them you can make accurate predictions. (But several explanations may be equally good.)Are you sure now what’s inside the cylinder? Why?

Coming up with a good explanation is an excellent achievement. But you still don’t know for sure what’s inside: you would have to look.Do you think everyone found the same solution? Compare the solutions.

There are many possible solutions: Figure 13.9 shows a few. This also indicates that we still don’t know for sure what’s inside the cylinder.How certain are you of your model? Does it need further testing? What would you do? How much more work is needed?

You’re only really finished testing when you know what’s really inside the cylinder. If your predictions keep turning out to be correct, you may claim that your model is very good. But all models in the figure predict the same things, so which one is the one that shows the real inside?

Reflection. Is this science?

Why didn’t you all find the same answer?

It depends on your imagination and ideas, which are different for everyone. The same goes for scientists. Scientists also can’t always open things up to see how they work inside and often only see the outside. If you try to “open” it, it often won’t work anymore.

Opening the cylinder? Let whoever really wants to open the cylinder do so now. Real scientists would also look inside the cylinder if they could because they are terribly curious. But very often in science, there is no way to ‘open’ what is being studied.

Physics background#

Many of the things you do to solve the cylinder puzzle resemble what scientists do during research:

You collect data (observe what happens when you pull the knots and then write it down).

You draw conclusions from the data (for example: it doesn’t matter which string you pull, a piece always comes out while the protruding piece goes in).

You make a model (you use your knowledge, imagination and creativity to think about what could be inside the cylinder, perhaps make a diagram).

You use your model to make predictions and test those predictions.

Maybe you refine your model during or after testing the predictions.

There are also differences with the work of scientists. In the universe that scientists study, you often can’t open things up to see the inside. It is impossible to open Earth and see how gravity really works, or what the inside of a molecule really looks like, or how evaluation really operates. Theories can be used to describe observations and make predictions perfectly. By making more observations and adjusting their models, scientists gain more insight into what happens and how it works. They use their creativity and imagination, and while they strive for a single correct solution, often come up with different, contended answers and predictions. They can test these and improve their explanations and models. But they are never completely finished, and what they know is never absolute and completely certain.