13.5. Magic, trick or physics?#

Nature of Science with a siphon

| Author: | Peter Dekkers |

| Time: | 30 minutes |

| Age group: | 14 - 18 |

| Concepts: | Nature of Science, siphon |

Note

The video is a little different from the performance described below. In the actual demonstration pouring the fluid collected on the right in the funnel on the left should start the water flow. Moreover, the larger the bottle inside, the longer the water keeps coming and the more surprising the phenomenon!

Introduction#

Demonstrate a surprising phenomenon and use it to develop understanding of the Nature of Science. It’s about the journey, not the destination.

This demonstration is an idea from and further described in.

Fig. 13.10 The Magic box.#

Equipment#

2 large beakers

1 small beaker

Food coloring

Water

Box

About 1.5 m of water tubes;

2 funnels

Double-sided tape or tape

Water-resistant caulk or glue

Empty bottle

Overflow vessel

Preparation#

Place the box on a short side, lid at the back. Drill two holes on top, place the funnels in them. Drill a hole on each side of the box. Attach a tube to the first funnel (on the right), feed it into the overflow vessel, and lead the overflow tube to the outside through a hole on the side. Place the overflow vessel so that the overflow point is above the lowest point of the outflow tube. Place a large beaker underneath.

Fig. 13.11 The Magic box (see Figure 13.12 for a schematic of the left side).#

Do the same for the second funnel, except that now there is a siphon between the inlet and outlet. Make the siphon by removing the bottom from a water bottle. Drill a hole in the cap of the bottle, attach a long piece of tube, glue the tube securely, and put the cap back on the bottle. Now invert the bottle and suspend it inside the box, below the second funnel. The outlet of the second funnel should let the water enter the inverted bottle: make sure there is no leakage.

Guide the tube coming out of the cap to go up, and let it turn back down just below the top edge of the inverted bottle. Then lead it out of the second hole on the side. The outlet of this tube should be situated lower than the lowest point of the inverted bottle (so that it empties all the way). Place a large beaker also below the second outlet.

Secure everything well. Make the tubes on the outside of equal length. Ideally, the box looks symmetrical from the outside. Finally prepare a small beaker with some water in it.

Fill the overflow vessel entirely with tap water.

Fill the siphon with water and some food coloring up to a point just below the point where the tube turns back down. The amount of water in the small beaker must be enough to make the level in the siphon rise and the water to go ‘over the top’ in the tube, and start the siphoning process.

Procedure#

Ask students to pay close attention so they can later describe exactly what they saw. Then pour the water from the small beaker carefully into the first funnel. Collect the outflow in the large beaker and pour it back into the small one. Have students write down their observations.

Expected statements: you pour water into the funnel on one side and it flows out through the hose on that side.

Next, pour the contents of the small beaker into the second funnel. If properly tuned, nothing will happen at first, but then liquid will start flowing out of the tube. Soon students will notice that the color is different. Then they’ll see that the outflow goes on for a long time, filling the large beaker almost completely. Does it ever stop? Yes, eventually it does. What’s in the box? Ask the students to come up with an explanation and make a sketch of what they think is in the box so as to explain what they saw. Make sure they also include the initial observations involving the first funnel. Let them discuss with each other: do their sketches explain all the observations?

Tip

To help students make a sketch, you can provide a sketch of the outside of the box.

After the sketches have been made and discussed, ask students if they are sure about what they have sketched below the first funnel. They have probably predicted that the water that was poured in is the water that came out, and that ‘nothing happens’. So what if we pour colored water into the first funnel? After students have made their predictions, pour the same amount of water as you started with, but now colored, from the small beaker into the first funnel. The liquid that comes out will be colorless (or much lighter than what you pour in). Ask students if they want to revise their sketch, and if so, allow them to do so.

Select questions for the follow-up discussion:

You’ve come up with an explanation, but where did it come from? What did you use to find it? (Creativity, imagination, experience, knowledge.) Scientists depend on the same traits.

If you have figured out an explanation, is it necessary to test if it’s correct? Why, or why not? In what ways could you test your explanation? Do scientists also test their explanations, and if so, how?

Different explanations have been suggested in class. Which explanations are better? What makes one explanation better than another?

Did you change your sketch of what is below the first funnel? If so, why? In science, can explanations also change, if more data become available? But if scientific knowledge can change, is it reliable?

Are we sure that our best explanation describes what is actually in the box? Can scientists be sure that their best explanations describe the world as it really is? Why do you think so?

On the side#

The following aspects of Nature of Science can be clarified based on discussing these questions. See also the introduction on NoS.

Curiosity is a key driving force for scientists. If they don’t understand something, they don’t become disappointed but interested and excited.

If you need to explain something you don’t understand, you start by using knowledge you already have. Scientists do the same. For example, water is a clear liquid whose color and quantity do not change on their own. So you probably did not find the first event surprising. There was nothing to explain, what happened fit in with what you already knew.

But then the amount and color changed. To explain that, you used your knowledge and experience, but also your creativity and imagination. Scientists also use creativity and imagination when inventing explanations!

Explanations are not simply accepted by other scientists, they will be thoroughly tested first. There are various ways to do this. For example, a powerful explanation will enable you to make correct predictions of what will happen if you repeat the experiment, or if you change it a little bit.

Did you correctly predict what happened when pouring colored water into the first funnel? Do you think scientists too can make incorrect predictions if they use scientific knowledge?

Scientific theories and models allow scientists to make incredibly many predictions that are enormously precise and accurate. In very many cases their knowledge is trustworthy and useful. But not always, it is in principle always possible that reality turns out to be different. But when that happens that is also an opportunity to improve the theories and models, and learn new things.

Physics background#

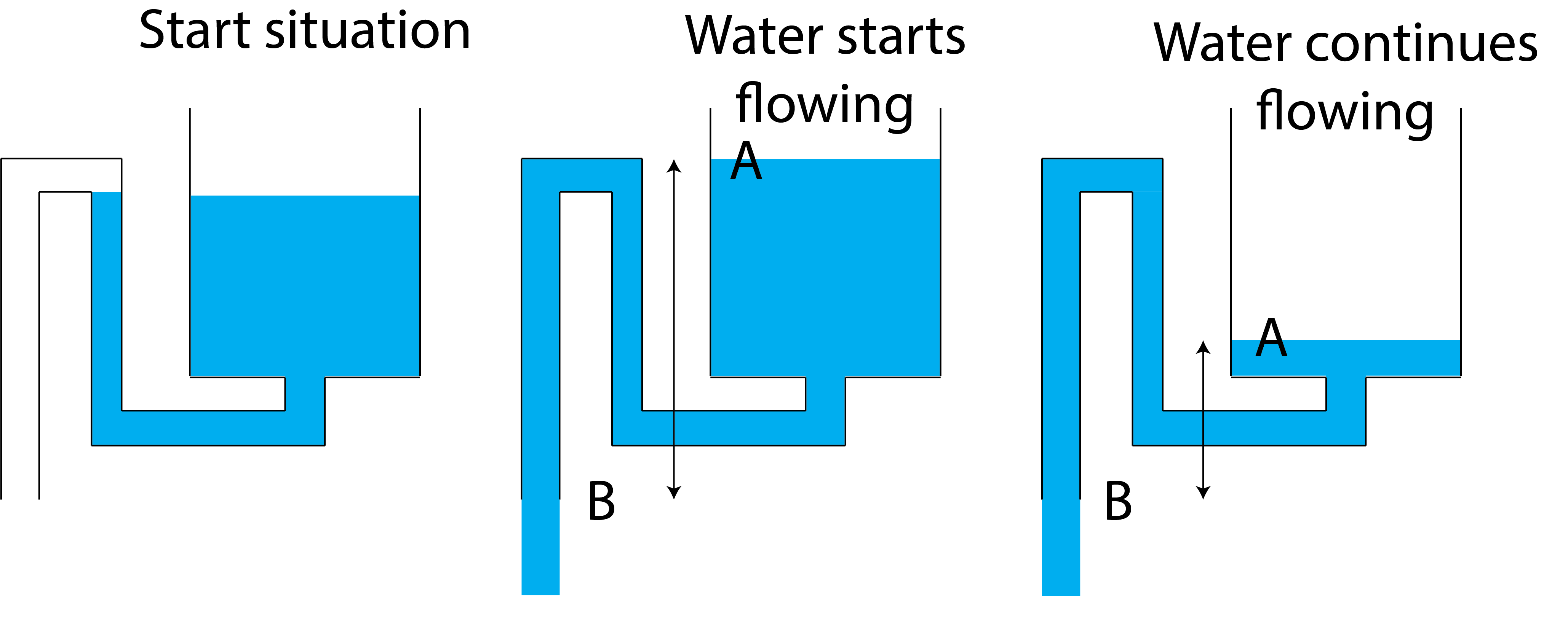

Looking at Figure 13.12, initially, the siphon is almost filled to the top (left). With the little extra liquid from the small beaker, the liquid at A turns the corner. The upward and downward parts of the tube remains completely filled throughout the process. The force that drives the water out of the siphon and into the tube is due to the pressure difference between A (1 bar) and B (liquid pressure at depth AB). This becomes smaller as it empties, but is zero only when the siphon is completely empty (if the set-up accords with the diagram).

Fig. 13.12 Diagram of the siphon, connected to one of the funnels. At the start, the siphon is almost completely filled with water and some dye.#

Tip

Completely emptying a siphon remains peculiar, of course. Feel free to turn the box around, show the inside after the discussion and show how it works. Perhaps searching for good explanations is just as important as having them.