9. Nature of Science#

As a physics teacher, you are responsible for imparting knowledge to your students, but also for conveying an idea of what natural sciences are and what scientists are trying to accomplish. In an era when (social) media sometimes spread nonsense about science, it is important that as a teacher you counterbalance that. Indeed, wrong ideas about science carry risks, as we saw during the recent corona crisis in which science was sometimes dismissed as “just another opinion” and scientists were even threatened. A good understanding of Ohm’s law is important for passing a test, but a correct understanding of the meaning and purpose of science are just as important.

But what image of the natural sciences should you convey as a physics teacher? What characterizes science? How is science different from art or religion, for example? And how do you handle that in your physics lesson? Such questions are discussed in the professional literature under the label “Nature of Science” (NoS).

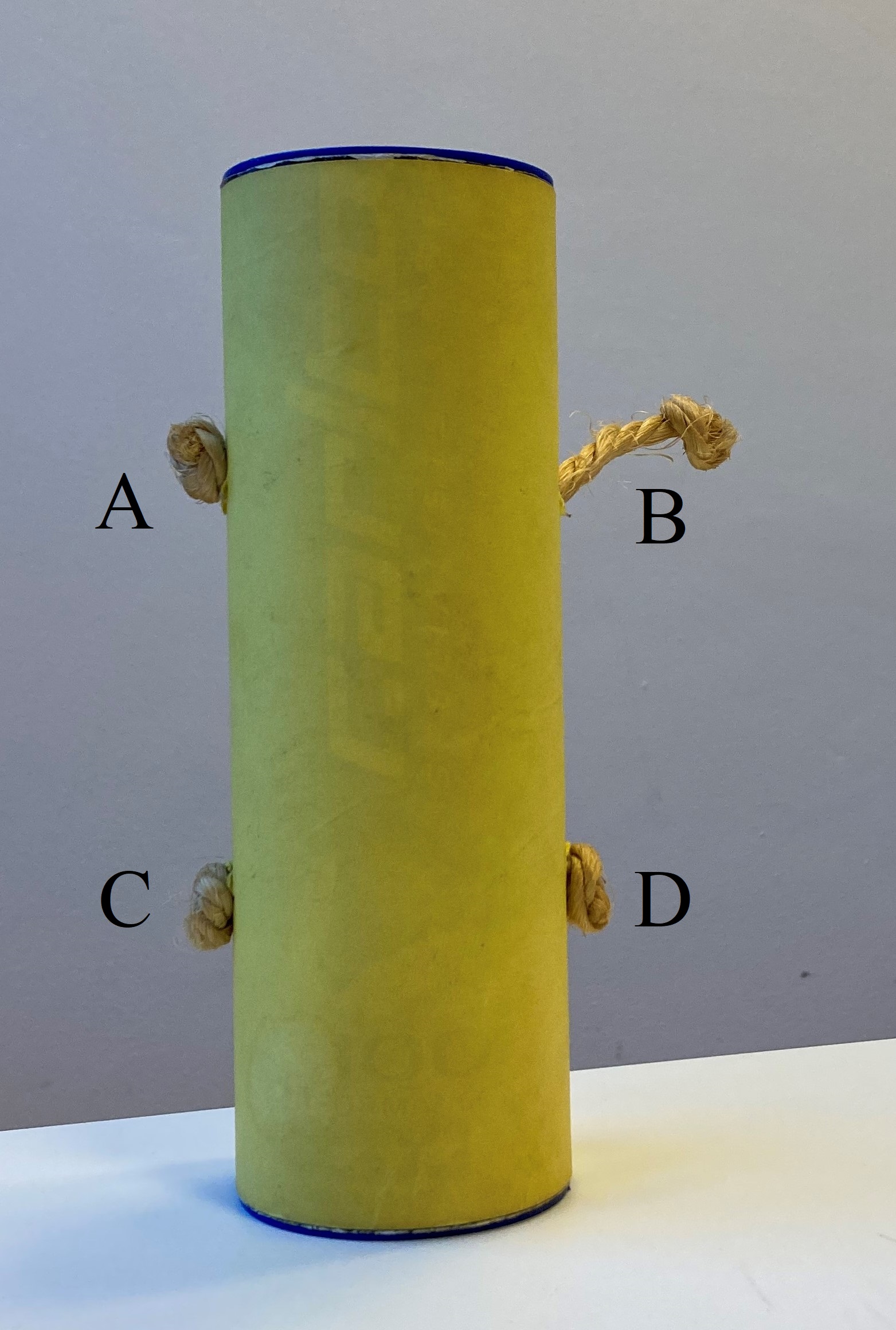

Fig. 9.1 Nature of Science activities often include decontextualised Black Box experiments []. ‘What is inside?’ is then the central question, addressing learning goals like ‘our knowledge is limited and we cannot always be certain about everything’ []. Figure created with AI.#

9.1. Why focus on NoS in physics class?#

The question of what natural science is -philosophically speaking- can perhaps never be answered satisfactorily for everyone. But for school purposes there is no need for that kind of answer. It is sufficient to teach students important features of natural science on which there is general agreement. When you do so successfully, your students understand what natural science is, what to expect from it and what should not be expected. This should enable students to participate as empowered citizens in societal discussions about issues with a scientific background and to make decisions in their personal lives, for example about vaccinations or environmental issues.

For the vast majority of students, this “scientific literacy” is more important for their future lives than substantive physics knowledge is. In addition, paying attention to NoS can make education more interesting, engaging and motivating for many students. Teaching NoS is worthwhile for that reason alone.

Teaching with attention for NoS may be easier than you think. It often merely requires that you avoid doing things you are used to doing. For example, one thing to put off for as long as possible is to give the “right answer”. At school ‘knowing the right answer’ often seems to be what is most important, and “wrong answers” are quickly dismissed. In science, however, scientists are constantly searching for possible explanations and seek to convince others of the correctness of their methods and answers. ‘Having’ correct answers when doing science is less important than being able to search for answers and to defend the ones you find. To clarify this to students it is better to delay giving the “right answer” at first and focus instead on the process of searching for the most acceptable or best defensible answer.

9.2. Thoughts and insights#

Customary education often produces conceptions of science that are unrealistic or even detrimental for how students view and value science [McComas, 2020]. Including NoS in education is meant to address this problem. Table 9.1 provides some examples of messages that customary education may convey and the undesirable conceptions of science that may ensue.

Messages that physics classes can unintentionally convey |

Unwanted conclusions students may draw from it |

|---|---|

Scientists are not creative: they just follow set rules and methods. |

Physics and other natural sciences are boring. |

Carefully collected evidence leads to unambiguous and certain knowledge |

Scientists cannot interpret data in various ways. |

Scientific models represent reality in the best possible way. |

If several models exist, only one can be the right one. |

Science is universal and scientists are absolutely objective. Therefore, good scientists always agree with each other. |

If scientists disagree, we cannot trust them. |

While the above views of science are clearly not desirable, it is not easy to find a suitable alternative in your lesson. It is important, of course, to show that scientists work in a systematic and structured way and that this has enormous advantages. Students also need to know that there are reliable models for carefully describing, explaining and predicting processes and events. There is no need to hide scientists’ commitment to consensus and objectivity. But it is truly a shame if we do not also show students that science is, in principle, always open to criticism and improvement. This is not a weakness, but a strength! It is precisely this that makes the growth and development of scientific knowledge possible, and distinguishes the natural sciences from dogmatic and rigid explanatory models.

Table 9.2 shows examples of some of the characteristics of NoS about which much has been written in the science educational literature. It includes examples of desired and undesired views for each characteristic. The desirable views reflect the current state of the scientific literature on NoS. The table is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to be given to students, but it is very suitable for reflecting on your own view of NoS.

Nature of Science aspect |

Example of common view |

Example of desired view |

|---|---|---|

The role of observations, experiments and consistency with scientific theories |

The only way to gain knowledge is to do experiments. Observations and experiments can prove scientific theories. |

Scientists use various methods (including experiments) and mutual exchange to develop scientific knowledge. Observations can support or refute scientific theories, but not prove them. |

Scientific theory |

Theories are vague conjectures. (In colloquial language the term is often used in this way). |

A scientific theory - for example, the theory of relativity - is a coherent structure of validated and generalized accepted explanations of phenomena. (Make students aware of the difference between everyday language and professional language.) |

The role of scientific models |

Scientific models are faithful copies of reality. |

Models are representations designed to explain or predict certain aspects of phenomena. Therefore, different scientific models relating to the same phenomenon exist. |

Provisionality of scientific knowledge |

Scientific knowledge is certain and immutable. |

Scientific knowledge is enduring and reliable but is fundamentally always open to development, change and improvement. |

Creativity in science |

There is only one step-by-step way for doing scientific inquiry (the scientific method). |

There is no such thing as “the scientific method”. On the contrary, scientists try to increase scientific knowledge in different ways. This often requires creativity. |

Subjectivity in science |

Scientists are objective and therefore only one correct interpretation of observations is possible. |

Although scientific research strives for independent knowledge, it remains a human product. This means that science is influenced by historical, cultural, social and economic conditions and by personal preferences of researchers. There is a difference between observation and interpretation. |

Controversies in science |

Fellow researchers immediately recognize and accept new scientific knowledge. |

Discussions and disagreements about scientific ideas are essential to scientific development. Different interpretations can coexist. |

Scientists |

Only in Western culture does one practice physics. It is only for boys. |

People (women and men) from all cultures contribute to science. (Two reasons why we know mostly white men as scientists: Other groups of people were denied access to education, and textbooks usually say little about the influence of scientists from other cultures.) |

9.3. How can you pay attention to NoS in your teaching?#

An excellent start are Black-Box activities, especially if they evoke immediate surprise and confusion. In these, you perform some small experiments with a certain object (the Black- box). The result is some kind of output produced by the Black-Box. But the mechanism that produces that output remains hidden. Students should feel that they ought to understand “how it works” and immediately feel the urge to investigate. In a demonstration, you then have excellent opportunities to direct their inquiry and explore together. See for example the NoS activities ‘Cylinder puzzle’ and Magic, trick or physics? in this book (both adapted from ), or check out this English-language website of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Fig. 9.2 Cylinder puzzle as an example of a model of the universe.#

Students get a feel for “doing science” when conducting their own inquiry, but tend not to learn NoS directly from their experience; messages about ‘what science (or scientific knowledge) is’ need to be made explicit. The same is true of student practicals, and even when students participate in real research projects - for example, during internships - they do not automatically and spontaneously develop understanding of the nature of the natural sciences. That development requires that you help students reflect on what they were thinking and doing during the investigation, and to compare that with how scientists think and work. For example, discuss with students why one particular explanation is inferior to or better than another. Discuss, in retrospect, how they made decisions during their investigations. So reflect with students on what they themselves experienced and draw explicit conclusions from that about what science is and how scientists work. Students’ own experiences from research then help them give content and meaning to NoS. If you teach NoS as “dry” text to memorize it is soon forgotten.

9.4. Demonstrations as a NoS activity#

Any demonstration and experiment can in principle be made into a NoS activity. There are stable elements that fit into almost all demonstrations. For example, you can ask the following questions about their statements:

Did you actually see it and really observe it, or infer it from what you saw?

Especially young students tend not to distinguish between observation and interpretation: what you see, what you think it is and what it actually is are not differentiated. In the demonstration called “Magic”, you pour a transparent liquid into a funnel and then collect about the same amount of transparent liquid in a beaker. Is that the same liquid? Is it water? The rest of the demonstration shows that you can’t just assume that it is. What you see may not be what you get.What did you observe? Did others notice that too? Was there anything else you noticed?

Perception is not automatic. It is influenced by your knowledge and expectations. When you know what to look for you see more, and that is true also in science. Fleming’s discovery of the effect of penicillin based on some forgotten bacterial cultures is certainly no exception. If you don’t tell students what you want them to see but leave that up to them, the variety of observations turns out to be enormous. This is not always desirable, but can help if you want to demonstrate the importance of focused observation in research.How did that come about? Can you explain how that happened? Are there any other possible explanations?

In the “Cylinder Puzzle,” use students’ own descriptions and explanations to discuss NoS. It is important to use a demonstration that is simple enough to allow for students to compare the quality of their explanations.What can we do to see if your explanation could be correct? How can we test your hypothesis?

An explanation has no value unless it fits the observations. It is stronger if it fits better and excludes more alternatives. Coming up with your own tests for explanations is important and instructive. This is another reason for not forwarding the “right answer” too soon.Have we now proved with this research that our conclusion is true? (For example, have we proved Hooke’s law?)

The concept of scientific proof is tricky. You cannot prove Hooke’s law in the same way as the Pythagorean theorem: the latter requires no observations. Moreover, from a finite number of observations you can never logically draw an inference about all the observations yet to come: this is called the ‘problem of induction’. Nevertheless, the validity and reliability of the observations in a study contribute to the quality of the conclusion.

As a teacher, the art is in properly assessing when and with which students you can go deeper into a particular feature of NoS. If you are open to it, very useful conversations can arise. For example, discuss that an “experiment” is by definition an investigation in which variables are controlled (i.e., held constant). Such experiments are crucial in physics and chemistry, but in astronomy or paleontology there are other methods of investigation as well. Students may think that scientific knowledge can only be gained from experimental research, but there are all kinds of acceptable scientific research, experiments are only one form. Especially for those who command Dutch: For more engaging and often philosophical questions about NoS that you can use directly in the classroom, check out the Flemish website http://www.wetenschapsreflex.be.

And if you want to talk to your students about stereotypes (Why do so many people think science is mainly for white men?), Margriet van der Heijden’s book “Ongekend” gives fascinating insights into how women were often systematically opposed and how their important contributions to science were forgotten.

9.5. References#

William F McComas. Principal elements of nature of science: informing science teaching while dispelling the myths. Nature of science in science instruction: Rationales and strategies, pages 35–65, 2020. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-57239-6_3.