13.1. The returning can#

| Author: | Peter Dekkers |

| Time: | 5-15 minutes |

| Age group: | 14 - 18 |

| Concepts: | Torque, spring energy, kinetic energy, equilibrium |

Introduction#

This demonstration is meant to evoke fascination and amazement while simultaneously illustrating aspects of nature of science. Physics in school may seem like a subject where all the answers are already known, and where imagination or creativity have little relevance. But in this ‘black box’ demonstration, it’s about the suggestions, ideas, and solutions that the students come up with. The correct answer is less important.

Equipment#

Empty can with opaque lid;

Some rubber bands;

A heavy, small object;

Awl or sharp screwdriver.

Fig. 13.1 This can comes back when rolled away.#

Preparation#

Punch two holes about ½ cm apart in the center of the lid and also in the center of the bottom of the can.

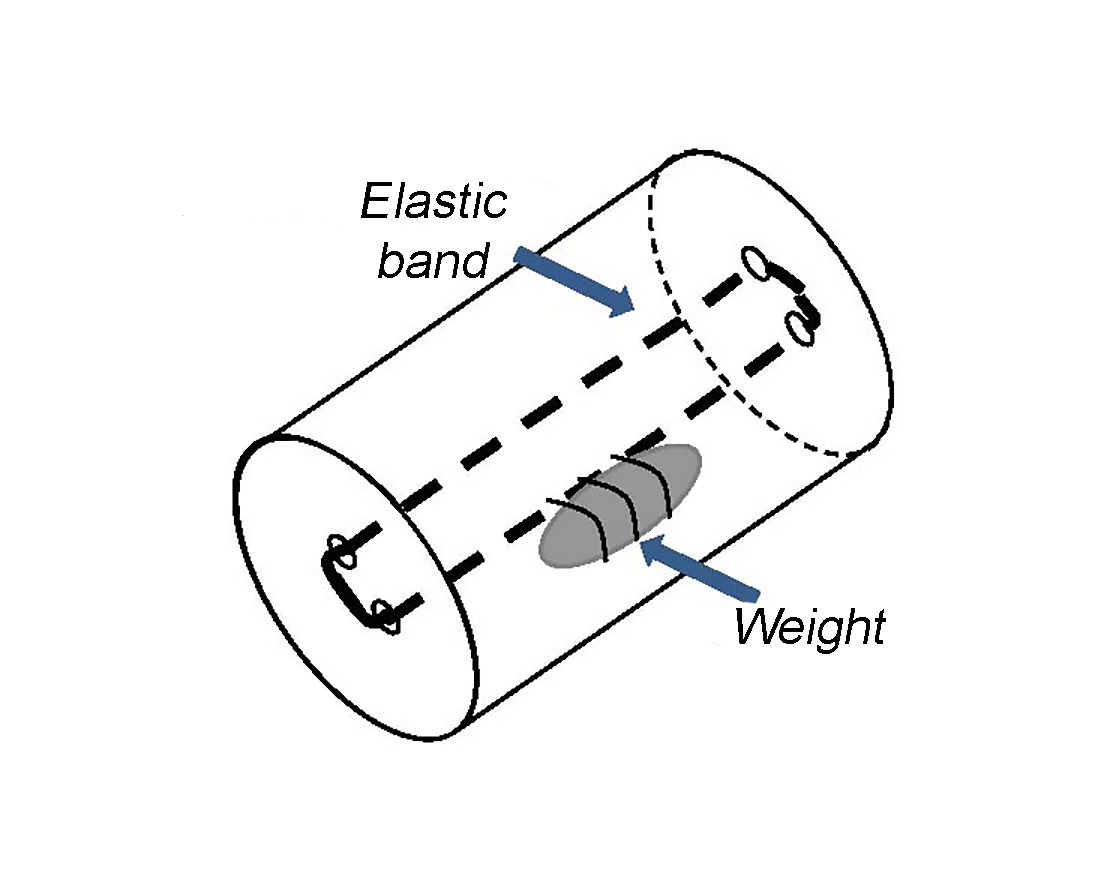

Cut one or two rubber bands, thread them through the holes, and tie them tightly to create a taut elastic ring: see Figure 13.2.

Fig. 13.2 Inside of the can: schematic.#

Attach the weight or stone to one side of the ring.

Close the lid.

Test your setup by carefully but firmly rolling the can away. It should roll a few meters, then stop and return.

If needed, try it with a smaller or larger weight and a tighter or looser elastic band until you get the optimal effect. Make sure the weight is hanging in the middle of the can. In the shown example Figure 13.1, the weight is the heaviest cap from my socket wrench set.

Procedure#

Roll the can forward on a horizontal, smooth surface. Catch it upon return. Repeat this a few times. Also, start from the other end to show that there is no slope to cause the rolling back. Or use a spirit level to show the floor is level if your students are as critical as those of tester Karin Zeeuwen: standing at the other end doesn’t prove anything “because then you also turn the can around.”

Also let it roll without catching it: if configured well the can will roll back and forth several times before stopping. If you roll it away too hard, you usually hear a few bangs inside the can, and it doesn’t come back.

The next step is about student thinking - do not yet open the can but ask:

What do you think is inside this can? Make a drawing of its insides.

Explain (to each other) how you think it works, or what makes the can come back.

Next discuss the solutions students came up with. Some solutions will be creative, some simpler, others more technical. Which solution is the best from a scientific point of view? It’s likely that each student thinks his or her own solution is the best. But what makes it better, objectively? Which arguments count? Students are often much better at judging the quality of someone else’s solution than at judging their own - but in the end it’s the arguments that count.

Next, you may want to address the role of amazement, imagination, and creativity in science. It’s quite strange that the can comes back. Scientists get excited when something odd happens because that means they don’t understand it, so there’s something to be learned! That’s why research is done, which starts with coming up with all sorts of solutions and ideas about how things might work. Scientists usually think their own solutions are the best ones too, and they evaluate each others’ work to find the best solutions. Often, they conduct new research as a result of that as well.

The best solutions fit what is observable and measurable. For example, it would be odd if the explanation involved an electric motor since the can has no on/off switch or plug. It also helps if the solution is familiar somehow. Are there situations similar to this one, and does the solution resemble what happens there? For example, there might be something like a spring in the can that gets wound up and then unwinds. An explanation that makes use of an elf living in the can is unlikely to be taken serious - most of us have never seen one. The solution can also be built as a model to see if it works. Scientists use these and other methods to find the best solutions.

Scientists are never entirely sure of their solutions. Your class can be sure of the correct solution when you open the can and see the mechanism that is behind it. But, for example, you can’t open up the Earth to see how gravity works or an electron to see what electricity really is. In general, the world is often like a returning can that can never be opened. Therefore physics knowledge is never absolutely true and certain; in principle, someone can always come up with a better solution to replace the old one. For example, because it describes observations of gravitational or electric phenomena more precisely.

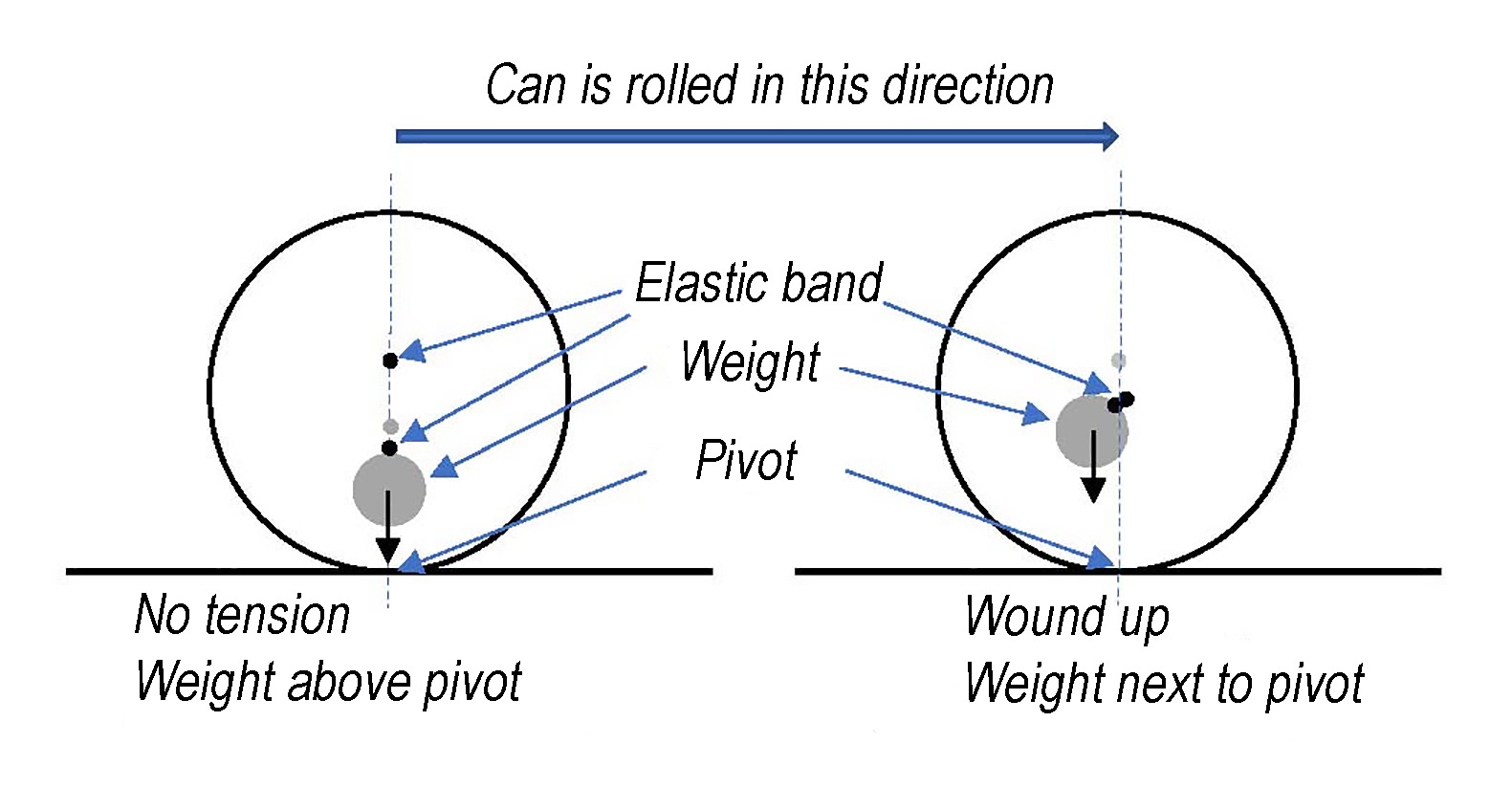

Fig. 13.3 Explanation - torque explains the return.#

Physics background#

Inside the can an elastic band is suspended with a weight attached to one side (on the left in Figure 13.3). When rolling the can forward, the two sides of the elastic band wind up around each other because the weight doesn’t rotate along but remains hanging in the middle. The elastic band tightens, causing the weight to be pulled upward and backward. When the can reaches the farthest point, the elastic band is wound up, and the weight hangs behind the point where the can touches the ground (on the right in Figure 13.3). This creates a backward torque relative to that pivot point. Thus, the can begins to roll back.

If you don’t catch the can, this process repeats in the opposite direction. If you roll it away too hard, the weight will be pulled over the elastic band a couple of times (banging against the can’s sides), the elastic band unwinds partially, and the can won’t roll back (completely).

Tip

Store the can for reuse. Releasing the tension from the elastic band slows its deterioration.

Follow-up#

Possible homework assignment before discussing the actual solution: try by yourself or as a group to make a can that rolls back on its own. It’s advisable to provide cans with holes for that.