13.8. Magic Memory Balls#

Density of solids and floating and sinking

| Author: | Bart van Dalen |

| Time: | 10 minutes |

| Age group: | 11-18 |

| Concepts: | Density, floating, sinking, buoyant force (Archimedes Law) |

Introduction#

In this demonstration metal balls change into ping-pong balls. Of course that is impossible, but the initial explanation of the presenter also does not make sense. So how does it work? A very simple demonstration that where the observations challenge the students to find explanations and engage them in reasoning with concepts as density, floating, and sinking.

Equipment#

Three metal balls

Three pingpong balls

Corn used for making popcorn

Small box or container

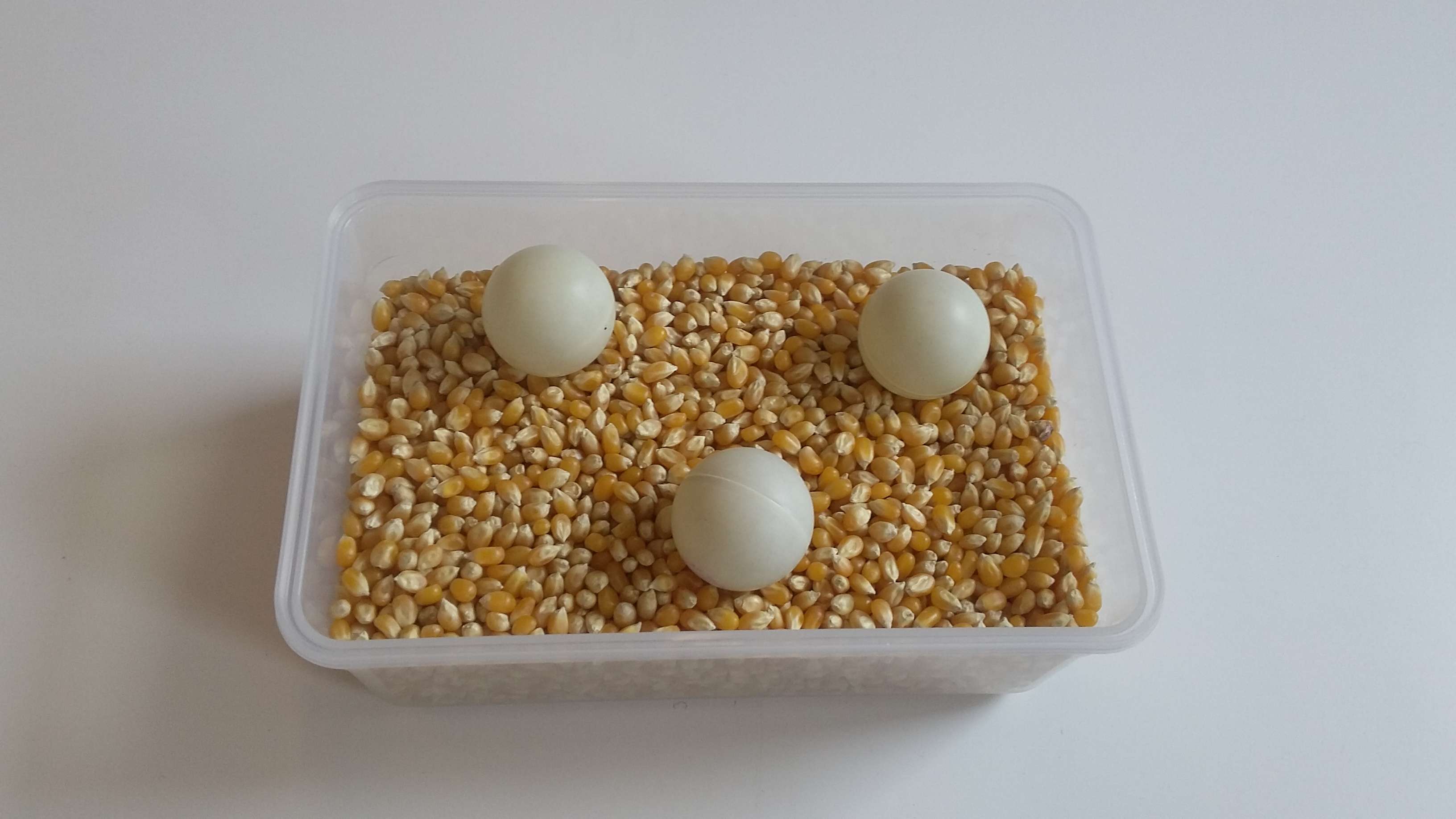

Fig. 13.16 Balls before the transformation#

Preparation#

Fill the container with the corn. Push the pingpong balls to the bottom of the container. They should not be visible. Keep the metal balls separate.

Procedure#

Show the metal balls to the audience, pass them along. Meanwhile tell them that they look like normal metal balls, but that they are made of a special memory metal. Put the balls on top of the corn and tell the audience they should assume these balls have similar properties as corn. Let the audience tell you what happens to corn when you make popcorn. Seduce the audience to use the terms “greater” and “white”.

Put the metal balls on top of the corn, then put the lid on the container and “heat” the corn by shaking the container. The metal balls will sink while the Ping-Pong balls will rise. Open the container: no more metal balls, but instead Ping-Pong balls (Figure 13.16)!

Fig. 13.17 Balls after the transformation#

Everyone can see with their own eyes that the steel balls ‘pop’ into ping-pong balls and yet no one believes that it is really so. Lively discussions can be started using the following ideas:

Is something true if you can observe it? Do observations provide a basis for absolute certainty? (A piece on empiricism, positivism and the theory-ladenness of observation. Optical illusions?)

What makes you believe someone or not? For example, no one believes the teacher in this demonstration, but many people do believe in horoscopes. Plenty of people believe that vaccines are harmful based on much less visible evidence than the teacher just gave of the ‘popping’. No one believes that ‘popping’ - rightly so, but how come? (A piece on conspiracy theories, the idea that new knowledge must fit with what you already know, the reliability of sources. The properties of ‘evidence’.)

What exactly have we observed? What changes have we made? Do you want to revise them? (First: the box contains corn and steel balls. Later: objects do not just come into being and disappear; metal does not just turn into plastic; all the balls must have been in the box. Conclusion: they are all still in there. Have students say as carefully and precisely as possible what they observed, what was surprising about it and why, exactly. Make it explicit that this is what you are doing with the class, as step 1 in finding a plausible explanation.)

If the conclusion is correct, the steel balls have sunk under the corn and the ping-pong balls have floated on top. Can you find an explanation based on that? (It is as if shaking the box is comparable to what happens when you put steel balls and ping-pong balls in water. Only you do not have to shake it. A bit about how logical reasoning and analogies are methods that scientists use in the construction of possible explanations.)

How would you test the assumptions and the possible explanation? (Two ways: explain from theory how corn kernels, water droplets and balls can move up or down using the concept of upward force, and for example perform measurements of that force on objects in water, or qualitative experiments.)

What have we not yet explained? (For example, in what way water droplets and corn kernels resemble and do not resemble each other, how shaking exactly explains how situations of ‘popping’ and sinking/floating differ and correspond.)

What does that have to do with science? (Summary, e.g.: in science, the idea is to find answers to questions about what you don’t know yet. Observations are very important in this, but not always reliable. The knowledge you already have is often also very important and useful: the analogy with floating and sinking in water helps, as does the idea that things don’t just come into being and disappear or change from metal to plastic. But that knowledge wasn’t enough: we’ve learned that corn kernels and water droplets sometimes apparently behave in a similar way. The concept of buoyancy shows how that works. But all sorts of questions remain: how exactly do those forces come about, what other situations can we understand with this approach? There are always things that scientists don’t know yet, and every answer they find raises new questions.

So science is producing more and more knowledge, but also more and more questions that haven’t been answered yet.

Physics background#

You will only understand the experiment when you become aware that there are two forces (neglecting friction!) acting on a metal ball and on a Ping-Pong ball. You have to compare these forces before you can predict what will happen. The corn exerts a buoyant force upward which for the metal ball is smaller than gravity but for the Ping-Pong ball greater than gravity. So the metal balls sink while the Ping-Pong balls will float on the corn.