15.7. Shadow of a flame 1#

Spectral lines

| Author: | Wouter Spaan |

| Time: | 5 - 15 minutes |

| Age group: | 16-18 |

| Concepts: | absorption spectra, emission spectra, formation of Fraunhofer lines, stellar atmospheres |

Introduction#

This demonstration is highly suitable for clarifying the paradox surrounding the formation of absorption spectra: a gas indeed absorbs certain radiation, but then emits exactly the same wavelength. So how do the dark Fraunhofer lines arise? This demonstration clarifies that those lines arise due to scattering.

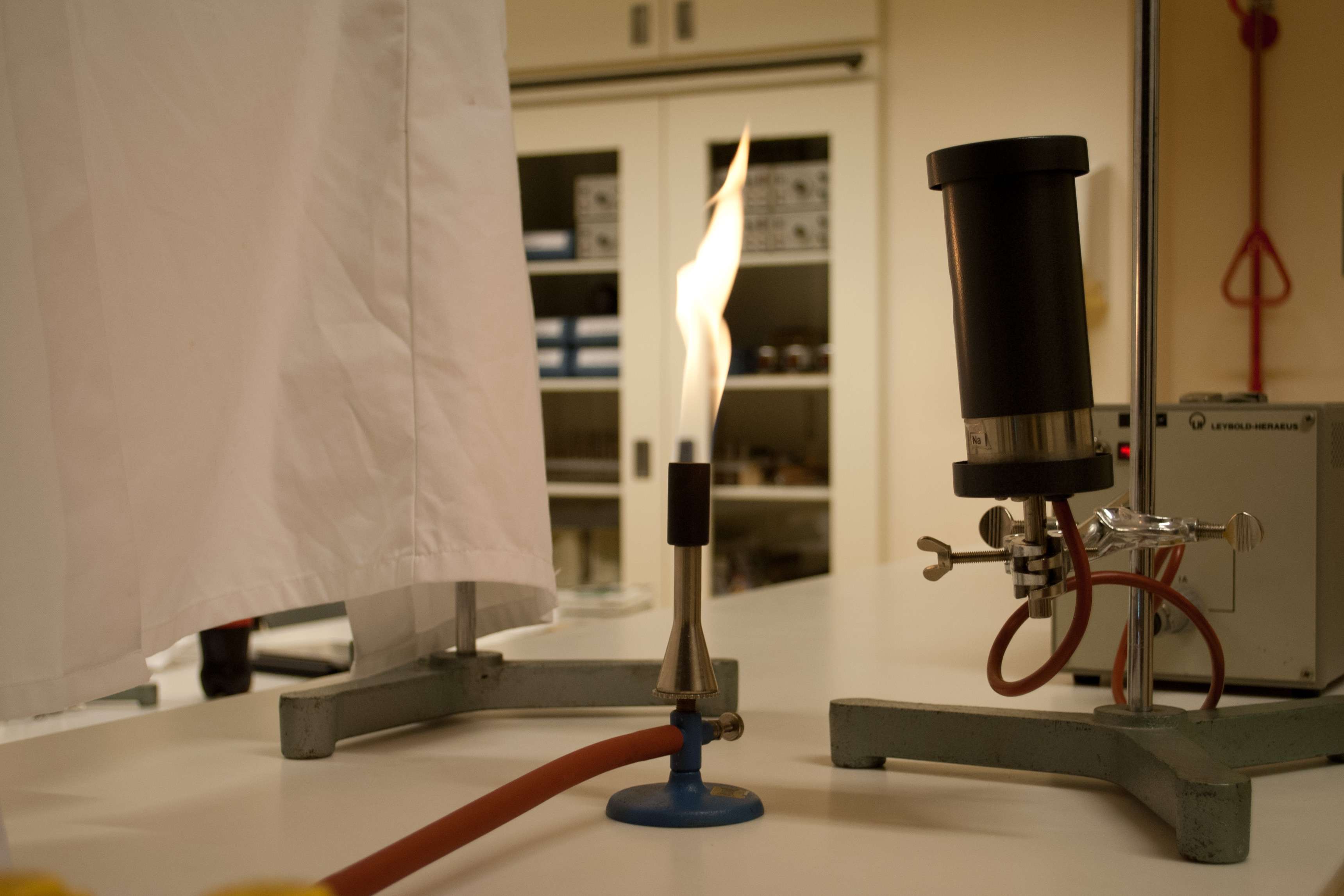

Fig. 15.19 Scattering, emission, and resulting absorption are visible.#

Equipment#

Sodium lamp

Bunsen burner

Transparent screen large enough to conceal the flame from view

Table salt (potassium salt can also be used)

Preferably a handheld spectroscope

Warning

Small amounts of sodium oxide and sodium peroxide can be formed. Both are irritating.

Preparation#

The setup is best built during the lesson. This to emphasize the sequence of events: first emission, then absorption, then observation. Turn on the sodium lamp in advance or utilize the warm-up time by discussing why the lamp needs to warm up. The classroom should be darkened for maximum effect, but the phenomenon is also visible in a non-darkened classroom.

Fig. 15.20 The setup: a sodium lamp, a blue flame, and a semi-translucent screen (a lab coat was used here).#

Procedure#

You explain the setup and places the screen between the flame and the class, completely obscuring the flame from view. It is intended that the students only see the shadow at first, without being able to observe the emission of the salt. Be mindful of reflective surfaces behind the flame (such as a whiteboard). By sprinkling table salt into the blue flame, you can make the flame cast a clear shadow.

Tip

Instead of sprinkling salt, you can also dip a paperclip bent into an eyelet and cleaned in a salt solution and hold it in the flame. You will have no mess this way.

The didactic value lies primarily in the follow-up: you ask for an explanation for the formation of the shadow, preferably with a schematic drawing of the setup and the process. You can also have the students predict the color of the flame. If desired, this can be done in multiple-choice form (transparent blue, opaque blue, transparent yellow, opaque yellow, transparent dark, opaque dark). Despite the fact that many students have seen sodium in a flame before, a reasonable number may choose ‘opaque black’ or ‘opaque dark’, apparently shadows are created by dark materials…

The setup can now be rotated 90 degrees to see for themselves. A number of students will be surprised when the flame becomes bright and opaque yellow. Now the class can come to the correct explanation and sketch, with some help from you.

The connection to the formation of the absorption spectrum in stellar atmospheres can now be quickly made.

Fig. 15.21 The shadow on the other side of the screen.#

Physics background#

The shadow arises because photons from the sodium lamp are scattered by the sodium in the flame. Photons are effectively absorbed by the sodium in the flame and then emitted again in a random direction. This causes the flame to be bright yellow in all directions. Only in the original direction of the photons are there fewer after the flame than before, while that effect does not occur for photons passing alongside the flame. We observe a shadow on the screen.

Note that the emission spectrum you observe in the flame consists partly of a true emission spectrum, because an electron will recombine with the sodium ion. The other part is a scattering spectrum, due to the absorption and re-emission of light from the sodium lamp.

Follow-up#

With a spectroscope, you can measure that the emission line of the lamp is the same as the emission line of the flame with table salt.

When using potassium salt, you will not get a shadow. Let students first predict whether a shadow will be formed.