22. Mechanics#

22.1. Free fall and independence of mass#

Break a piece of chalk into a small and a big piece and keep them between thumb and index finger such that the lowest ends are at the same level. Ask students to predict which one will hit the floor first if released simultaneously. Discuss predictions and reasons. Then let go, repeat until all observers agree. Explain. Alternatively use big and small coins or stones on your hand and pull your hand away from under the stones.

22.2. Can we accelerate our hands more than g? Proof it!#

Ask the question, let students answer, good chance they come up with a matching experiment. Easy actually, hold your hand flat with a stone or anything on it, then move the hand quickly down. The stone or other objects will be slower, there will be space between the objects and your hand. Students can do this in their seats. Make sure the hands are only accelerated down and not first up.

22.3. Fall and Air Drag#

Now let a sheet of paper drop. It swirls and drops slowly. Then crumple it, it drops almost as fast as a coin. Then take ½ A4 and put it on top of a book and drop the book. Paper and book will reach the floor at the same time! This happens even if you fold the paper in a tent shape so there is some air between the middle of the paper and the book. No need for the awkward vacuum tube to show that feather and lead ball fall equally fast.

Fig. 22.1 What will happen if you drop a paper on top of a book?#

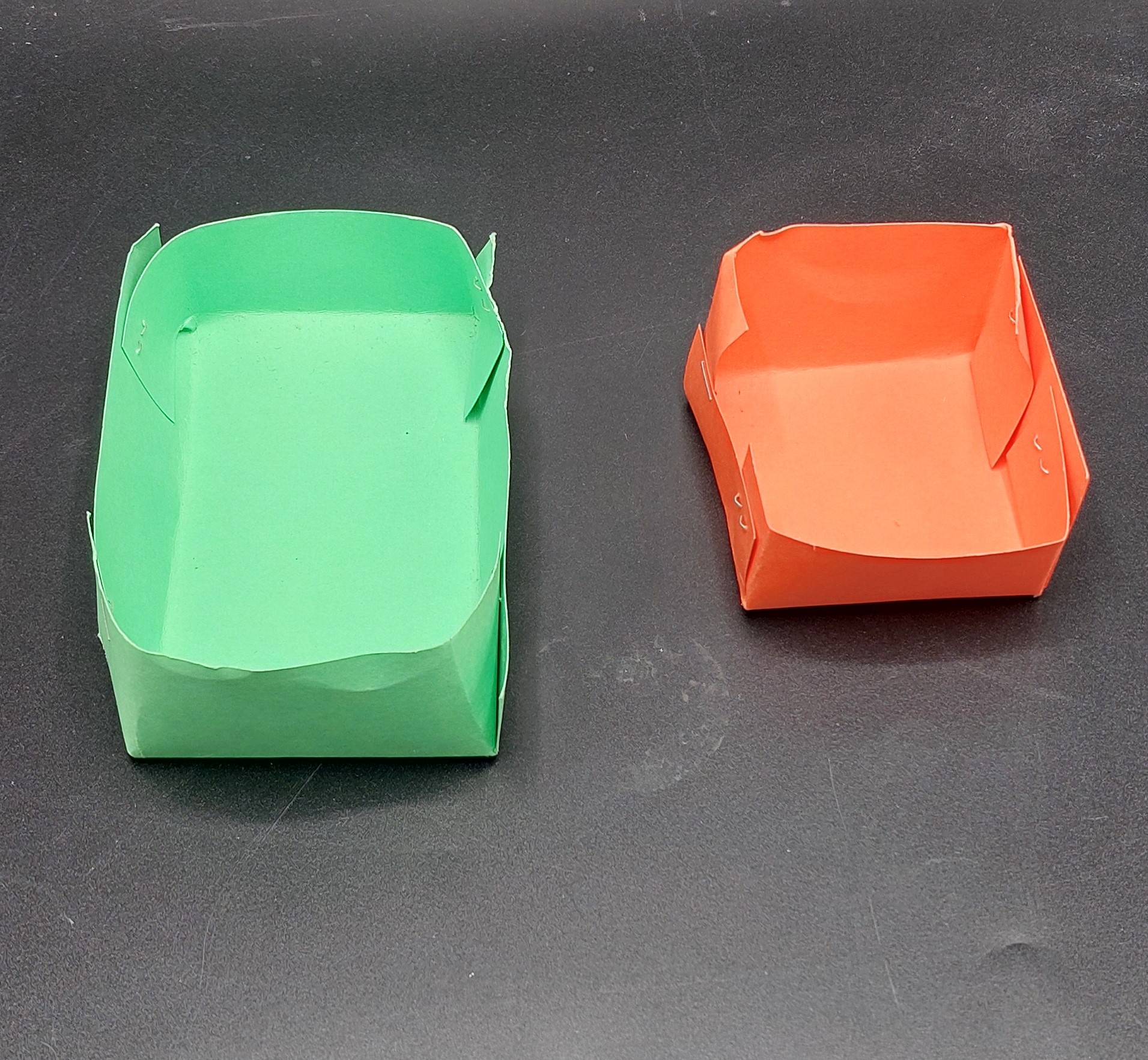

22.4. Paper baskets#

From one half A4, it is easy to fold a rectangular basket and staple it and add unused parts of the half A4 into the basket. A sheet of paper swirls down. However, the basket falls with an almost constant velocity. It is possible to convert this demonstration into a laboratory investigation in which students could investigate the influence of area and mass of the paper basket on the time it needs to fall from a certain height. A first approximation could be the formula \(t = \frac{h\cdot A}{m}\), so one would predict that doubling height \(h\) or doubling area \(A\) would result in doubling the fall time \(t\). These predictions can be checked by holding an area \(2A\) basket at half the height of the area \(A\) basket, release them and they should reach the floor at about the same time if the model is correct. For area it appears to fit, or would the air friction scale with \(v^2\) rather than \(v\)? However, for mass \(t\) scales with \(m^{-½}\) No stopwatch needed. An early version of this experiment can be found in @rogers2011physics [pg.167] famous book Physics for the Inquiring Mind.

Fig. 22.2 Which basket is faster?#

Fig. 22.3 Would the air friction scale with \(v^2\) rather than \(v\)?#

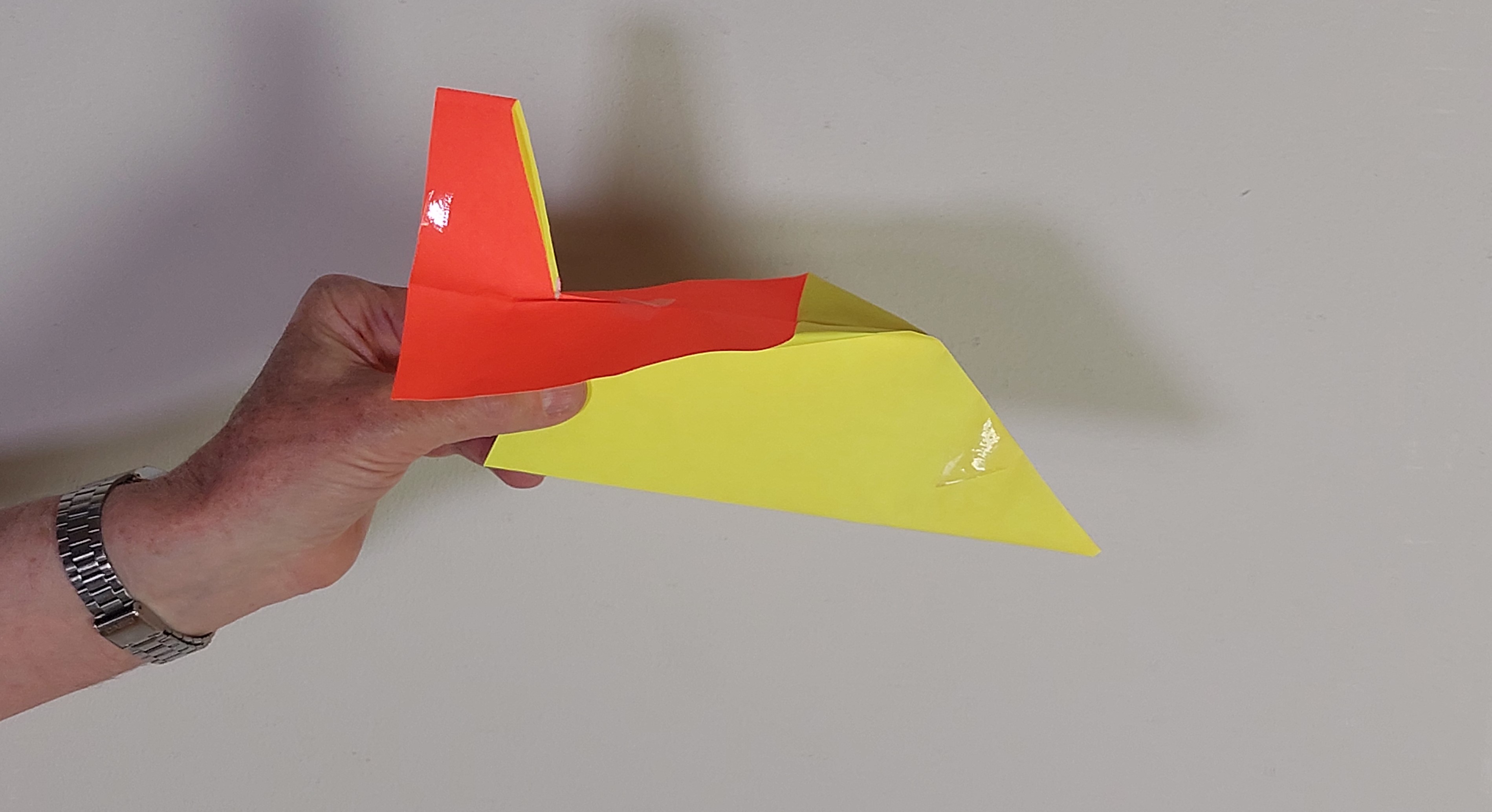

22.5. Flying is playing with air resistance#

There is always paper in the room or in the notebooks of students. Fold various shapes and drop them. Fold paper airplanes, there are many suggestions for paper airplane activities on internet. Including a vertical tail piece sticking out above the wings can greatly improve the range when thrown.

Fig. 22.4 Flying is playing with air resistance#

22.6. Kinematics#

Walk across the front of the room

at constant speed,

at a higher speed,

accelerated and decelerated,

stopping and going.

Let students draw distance vs. time and velocity vs. time graphs for each motion. Of course, you should have brought a motion sensor, but you were late or found the equipment room closed. The walking will do just as well or even better. Make sure to look at the resulting student graphs, discover conceptual errors, and react, typical student mistakes are well known and useful to confront [].

22.7. Relative motion#

Student A walks with a low constant velocity in front of the class from left to right. student B starts later, walks faster and overtakes student A. At the moment that B is next to A, are the velocities the same or different?

Strange question you will think, but some people will answer equal (misconception). In a traffic court case in the USA this opinion was even espoused by a judge. If none of your students go wrong here, then never do this demo again. Have your students draw position time diagrams for A and B in the same graph (see the previous demo).

22.8. Action versus reaction visualization exercise#

To point out the relevant forces and show what is meant by action = - reaction, not to proof it: a rubber band or piece of elastic band can always be found even in a bare classroom. A student may have a rubber band around a lunch box. Stretch it with your finger. The force of the finger on the elastic band equals the force of the elastic band on the finger. Point out that action and reaction always work on different objects. That’s why we want students to properly name forces as \(F_{finger on elastic band}\) and \(F_{elastic band on finger}\). The teacher can also put two students in front of the class, each with one hand pushing the hand of the other student but not moving. Then one student will push so hard that the other has to move back. Is now still \(action = - reaction\) or \(F _{student_A on student_B} = -F_{student_B on student_A}\)? Yes it is, but to understand why student B is moving backwards, one has to add the forces on student B only: > \(F_{student_A on student_B} + F_{friction floor on student_B}\)

22.9. Linear inertia 1, Newton’s First Law with a glass of water#

Take a glass of water (or a coin, or another object, breakable objects are preferred) and put it on top of a dry A4 sheet of paper. Pull the paper slowly with a constant velocity to the edge of the table. Then suddenly jerk the paper. The glass stops. What students feared, does not happen, unless the teacher is clumsy or the bottom of the glass was wet. The glass of water resists the sudden acceleration …. inertia!

Fig. 22.5 A piece of paper and a coffee mug, is always at hand#

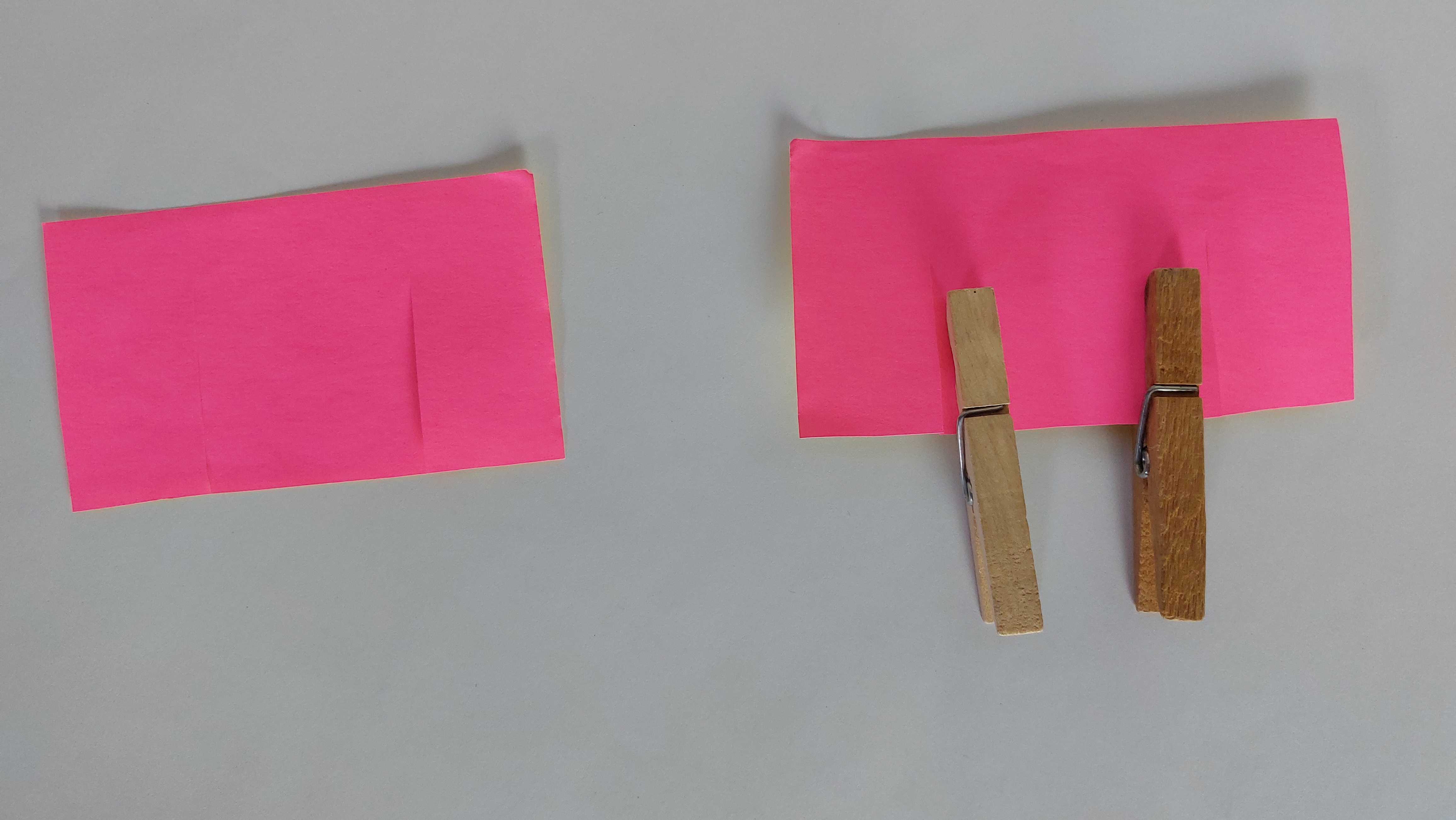

22.10. Linear inertia 2 with clothes pegs#

Tear a piece of paper as in Fig. 22.6. Can I tear both sides of the middle part in one jerk? No, does not work. What should I change in order to be able to tear the two sides off in one jerk? It turns out that if you make the middle part just a bit heavier by putting on a few paper clips, it will work (source: my former student Ruud Brouwer).

Fig. 22.6 Some additional mass in the middle makes sure the paper rips at both ends.#

22.11. Linear inertia 3 knife and apple#

Stick a knife in an apple, hold it up so the apple is suspended from the knife. Then start hammering. The apple resists acceleration and the knife goes farther and farther into the apple. If you use a big bread knife, it will come out at the other end. To make it more spectacular, use a bigger knife and use a melon or other big fruit, any relatively heavy fruit will do.

22.12. Rotational inertia with sticks, brooms, or a hammer#

Put a ballpoint straight up on your hand and try to balance it. You may invite the audience to do the same. It is impossible, it will tip over immediately. Now find somewhere in the classroom a meter stick, or a broom, or any stick longer than the ballpoint. Put it straight up on the hand and try to balance it. That works quite well. The object resists rotational acceleration ….. rotational inertia! The longer the object, the greater the rotational inertia, the easier it is to balance it. If then on top of the object there is an extra weight, like with a broom upside down, then it becomes easier yet. If you can find a hammer, you can show that it is easy to balance if the weight is up and difficult if the weight is down (metal top part on your finger). The taller the object and the farther the center of mass is from the pivot point on the hand, the greater the rotational inertia. Rotational inertia is often not included in high school physics, but that is no reason not to demonstrate it! Source: my former student Alfredo Guirit, from Tagbilaran, Bohol, Philippines.

22.13. Rotational inertia 2 with toilet rolls#

With a full roll just prepare the length you need then a jerk will suffice to get your piece of paper, see Fig. 22.7. If you do that with an almost empty roll, then the remaining part will unwind and give you much more than you need. The full roll has a higher resistance to acceleration, thus a greater rotational inertia. For a demo in the classroom, just borrow the rolls from the school and put them back later.

Fig. 22.7 What happens if you pull either of the toilet rolls?#

22.14. Rotational inertia 3 with string and breakables#

Now make the set-up of Fig. 22.8, preferably with a breakable object on one side of the string such as a porcelain cup instead of the keys, but any object will do. At the other end of the string an object such as a bolt or a screw or a key, whatever. There is a pen or pencil in the left hand as a kind of pulley. Then let students predict, If I let go of the string, what will happen? The teacher shows some uncertainty or even fear, would this go alright? Let go! The weight will be greatly accelerated and wind itself very quickly around the pencil. That will increase the friction so much that the cup (or keys) will stop falling. For an explanation try to link with the results of demonstration 13. A nice discussion of this experiment is on this Harvard site and this includes references to the American Journal of Physics [].

Fig. 22.8 Daday ready to drop her coffee mug, safely.#

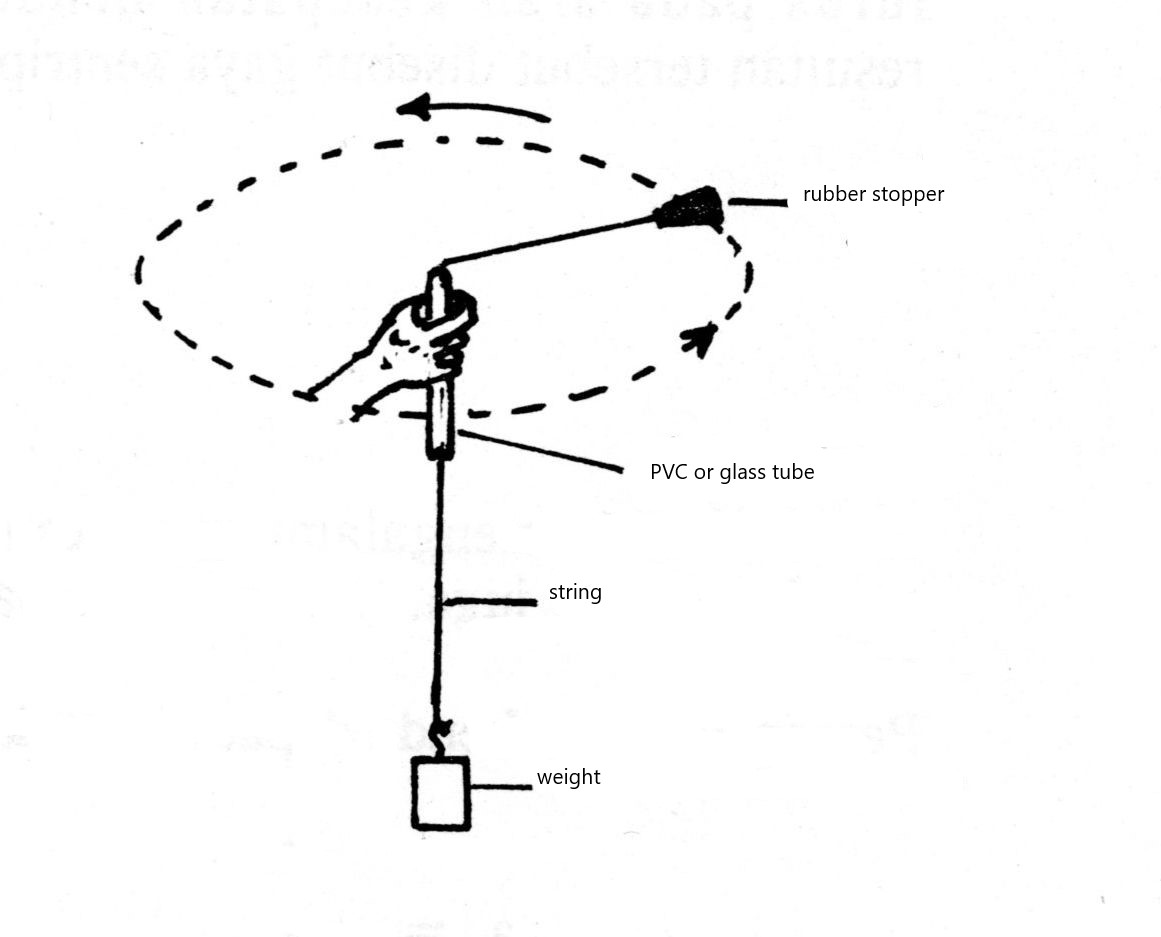

22.15. Circular motion 1 with string and stopper#

Now that we have the nice set-up of Fig. 22.9, we better also use it to demonstrate properties of circular motion. While the stopper is moving, you will cut the string with scissors just above the weight. Draw a circle on the board and let students predict whether the stopper will fly off radially or tangentially (draw the two possibilities). Let students write a prediction with a reason. Then cut the string when the stopper is moving away from the students.

Fig. 22.9 Demonstrating circular motion using a rope, pvc tube and some small weights.#

22.16. Circular motion 2 with string and stopper#

Just like in the earlier rotational inertia experiment, show what happens to the velocity when reducing or increasing the radius by pulling or releasing the string in the set-up of Fig. 22.9. Show also what happens to the velocity when you add weights while trying to keep the radius constant.

22.17. Circular motion 3 quantitative#

It is possible to make this into a quantitative demonstration supporting the formula \(F = \frac{mv^2}{r}\) by computing the velocity from measurement of the period T with a stopwatch or video from a mobile phone. Make sure to independently vary F and r while controlling for respectively r and F.

Fig. 22.10 Freek Pols performing the demonstration#

22.18. Projectile motion 1 with water#

Throw anything away from you, its path looks like a parabola. Now display it all at the same time, ask a plastic water bottle from one of the students, make a hole near the bottom on the side and squeeze it, nice parabola. Better visible if you use ice tea or other colored drinks instead of plain water. Compensate the student for the loss of the bottle and clean up if you forgot to bring a basin.

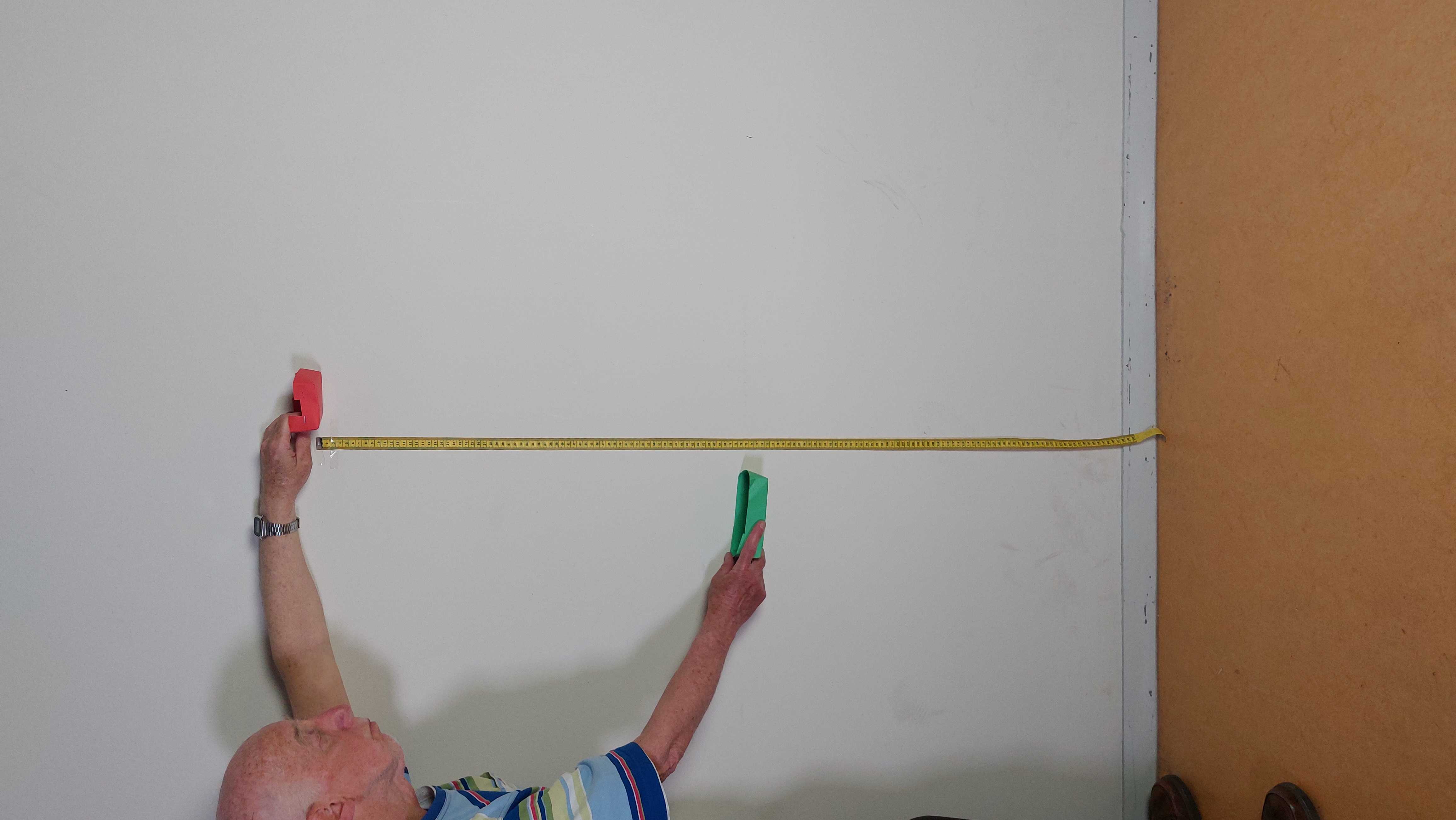

22.19. Projectile motion 2 independence of horizontal and vertical motion#

My wife Daday, also a physics teacher, made a clever device to show that the vertical motion and the parabolic motion of a projectile experience the same vertical acceleration, a free-falling coin and a simultaneously horizontally launched coin from the same height, will reach the floor at the same time. Just listen. To construct the launcher, just fold a piece of thin metal from a can over the end of a ruler.

Warning

better picture!

22.20. Projectile motion and relative motion#

Walk with constant velocity while throwing a piece of chalk or a coin or a tennis ball straight up. It lands in your hand, not behind you. So it had the same horizontal velocity as you when launched!

22.21. Air pressure with newspaper and ruler#

Did any student bring a newspaper to class? Or take one from the faculty room. Is there a ruler or thin piece of wood that could be broken? Have the piece of wood sticking partly over the table edge, put a few newspaper pages over it like a blanket and push out the air underneath. Then hit the part of the wood sticking out quite hard (let a karate student do this). The paper will not tear but the wood will break. Consider the piece of wood like a see-saw pivoting at the edge of the table. The force of air pressure on the newspaper competes with the force of the hand hitting the wood.

22.22. Static and kinetic friction and center of mass with a stick#

Take a ruler, meter stick, or any other long object available. Balance it horizontally on top of your left and right index fingers. Then start moving the fingers towards each other. Without any control by the instructor, the fingers will only slide against the ruler one at a time and the two fingers will meet under the center of mass. You can make it more spectacular by blindfolding the instructor, same result. The experiment could easily be repeated by the students in their seats, they can try their rulers or other objects from their bags. Explanation: when one finger moves, an increasing part of the weight will be supported by that finger as it gets closer to the center of mass, so friction increases, and the other finger will start moving until it stops and the process repeats itself. Also see the 34 experiments with rulers in the American Journal of Physics [@Ehrlig1994]. An interesting variation is to add an object on one side of the stick, for example a blackboard eraser or hang a bag, then using the above procedure you will find that the center of mass has shifted.

Fig. 22.11 Finding the center of mass can be done (and predicted) using various materials.#

22.23. Static and kinetic friction with stick and scarf#

Take a meterstick, or pvc tube, or any other rod such as the end of a broom. Keep it horizontal and hang over it a piece of cloth (towel, hand kerchief, scarf) such that one end is much longer than the other end but it does not move because of static friction. Then slowly tip the rod downward a bit until the cloth starts moving. It will then not just move downward, but also sideways. Friction has now become kinetic and kinetic friction is smaller than static friction thus insufficient to prevent sliding sideways (source: Ineke Frederik, Dutch physics teacher educator).

22.24. Friction 1 of paper and books#

Take one half A4 and put it between the pages of a closed book, pull it. It is easy to pull it out. Now take 10 of these half A4 pieces of paper and put them each between different pages. Try to pull out all 10 at once. That is difficult. Source: Leisink, 2006

22.25. Friction 2#

When students really need a time-out, let them then interleave the pages of two books. The books cannot be pulled apart. Well-known is of course the ideal version of this experiment where two traditional telephone directories are interleaved and handles are attached to the books. Two strong people cannot pull them apart, but that is not a pocket demo anymore, but it would fit in 2 minutes if the teacher shows a YouTube version.

22.26. Friction and heat#

Students rub their hands and feel the heat. Work converted into heat, or in a perhaps better formulation: work increases the thermal energy (or internal energy) of the skin.

22.27. Friction and normal force 1#

Put a book on the table, try to push it across the table. Have a student try. Then make a pile of books (borrowed from students) and try to push. It is much more difficult; the pushing force has to be greater. So friction has something to do with the total mass of the books, or, if the normal force has been discussed, friction is proportional to the normal force exerted by the table on the books. One can have students participate and feel it themselves by having them make their own pile of notebooks or textbooks on their tables or on the writing boards of their seats.

Fig. 22.12 What happens if you push one of the books? Does it matter where it is in the pile?#

22.28. Friction and normal force 2#

Take three textbooks and pile them flat on your hand and hold them up. Then with a finger of the other hand you are going to push the top book. Ask for a prediction, if you push the top book, will only the top book slide, or will two or three books slide? Why? Then show, only the top book will slide. Friction between the 2\(^{\text{nd}}\) and 3\(^{\text{rd}}\) book is 2x friction between 1\(^{\text{st}}\) (top) and 2\(^{\text{nd}}\) as friction is proportional to the normal force.

22.29. Friction and inclined plane#

Tilt the instructor’s table using an object under one of the legs or using a student to hold one side of the table up. Put anything round on the table (borrow some candy from students, instructor can eat it after use). The round object will accelerate down the table surface. Put a book on the table. What keeps it there? Friction. Increase the tilt, the book does not move yet. Is the magnitude of the friction still the same? Tilt more yet, the book starts moving. Why? Make sure to distinguish between actual friction (\(mg \sin(\alpha)\)) and maximum friction (\(μ_N = μ_s~mg \cos(\alpha)\)). The instructor can even illustrate how friction coefficients are determined by taking the static friction coefficient equal to: \(μ_{static} = \tan(\alpha_s)\) where \(\alpha_s\) is the tilt angle when the book is just about to slide. Dynamic friction occurs at an angle where the books once moving, keep sliding at constant speed \(μ_{dynamic} = \tan(\alpha_d)\).

22.30. Difference between static and kinetic friction#

Pull a student bag across the table with a piece of elastic band or a weak spring. Movement will be kind of jerky: stick-slip movement. The elastic band or spring will be longer when the bag is not moving and shorter when it moves, showing that static friction is greater than kinetic friction.

22.31. Strength of profiles#

Put a banknote on two markers. How can you fold the banknote such that it can carry a load of many coins? Two folds already helps a lot. If you pile more banknotes on top of each other, then they can carry many coins! Then try more folds, corrugated banknotes are very strong. Think also about all the roofing materials that have corrugated shapes rather than being flat, for example rooftiles and metal roof sheeting. A nice series of demos and comparison with carton and other materials can be seen here.

Fig. 22.13 How can you fold the banknote such that it can carry a load of many coins?#

22.32. Center of mass 1: make your students feel it#

Show with a stick or a ruler or a meter stick or even a broom stick what is the center of mass. Put the stick on the table, pull it slowly outwards over the edge. At a certain point it will start to tip over. If you support the stick at that point with your finger, the two sides will balance. That is the center of mass, it is as if all the mass is concentrated there. Human bodies also have a center of mass.

Stand up all of you. Lean forward. What do you feel? Cramp in your toes? Lean more forward yet, eventually you will have to take a step forward in order not to fall. The center of mass of our body is somewhere in the belly. If that center of mass goes over the toes, then we have to take this step forward to prevent tipping over. Could you lean forward more if you were standing on skies? Stand up again, lift your leg up (forward), your shoulders will go backward to balance, so that the center of mass is still above your feet. Lift your right leg sideways, now your shoulders will move in opposite direction. Sink through your knees, your brain already knows how to compensate, some parts of the body go forward, some parts go backward.

Every time your brain knows automatically how to compensate, that is built-in physics! A longer series of demo’s on center of mass along with some spectacular powerpoint pictures is available from the author.

22.33. Center of mass 2: students picking up money from their toes#

Line up some students with their back and particularly their heels against the wall of the classroom. Then put some money in front of their toes. If they can pick it up without falling, they may keep it. This is impossible to do without their center of mass going beyond their toes and falling.

Fig. 22.14 Impossible to pick up the money when heels at the wall.#

22.34. Center of mass 3: unequal student pair#

Take two students of unequal size next to each other facing the other students in front of the classroom. They hold each other. Then let them lift their outer legs. Total instability! Same problem, their common center of mass should be above their standing legs in the middle, but lifting their outer legs will disturb the equilibrium.

22.35. Center of mass 4: hammer and ruler#

Borrow a hammer and a stick and some rope or rubber bands and make the set-up of Fig. 22.15. Teacher education student David constructed and explained it perfectly.

Fig. 22.15 Balancing hammer#

22.36. Rotation, center of mass, stability#

Tilt a chair, tilt it more, there is a point where the chair will tip over. Take a simpler object, a book or a piece of wood. Try to link the position of the center of mass to the point where the book or block of wood will tip over. Take any other object in the room. When picking up a chair, boys tip over more easily than girls as their center of mass tends to be higher in the body. Instructions can be found in [@Liem1987, p326].

22.37. Pressure and surface area#

Take a pencil or ballpoint, press the tip (small surface area) on the inside of your hand, now press the opposite end on your hand (large surface area). The force could be the same, but the pressure is definitely different.

22.38. Simple machines: meter sticks and rulers as crowbars#

Usually there is a meter stick or something similar in the room. Use it as a crowbar and stick the end under a table leg or under a pile of books and pull the other end up. At a much reduced force, but increased distance, the weight can be lifted. Students can feel it themselves using their own rulers or even ballpoints and their usually heavy physics book which they should take to all class sessions anyway. Let them feel the difference by pulling on the middle part of the ballpoint and pulling at the end (much lighter).

Warning

FOTO

22.39. Torque of doors and door handles#

Illustrate torque opening the door, turning a doorknob, or tilting the chair. With torque we make things turn around an axis.

22.40. Torque and distance from axis#

Again, use the door. Push with your finger at the end, the door moves easily but the finger has to move a great distance to turn the door through 90\(^o\). Now push close to the hinges. The force needed to move the door is much greater, but the finger only has to move a short distance to move the door 90\(^o\).

22.41. Moment of force 1 stretched arm and bag of books#

Take a student’s bag with books, hold it at arm’s length and then hold it next to your body. Which one is easier? The moment of force, the product of force times arm, is greatest at arm’s length and we can feel that very well. Let the students do this themselves with their bags.

22.42. Moment of force 2 lifting bend and stretched legs while sitting#

All students sit on their chair. Lift one knee a bit up from the chair. No problem. Now stretch the leg and again try to lift the knee from the chair. It is a lot more difficult this time. The moment of force (force times distance from hip to center of mass of the leg) is much greater now.

22.43. Springs parallel and in series#

Collect some rubber bands from your students and arrange them parallel and in series and let students feel. This is like springs parallel and this is like springs in series. This can also be done with the springs from several ballpoints. In which situation, parallel or series, can one add up the spring constants? Just use logic first using Hooke’s Law \(F=Cu\) with \(C\) as the spring constant.

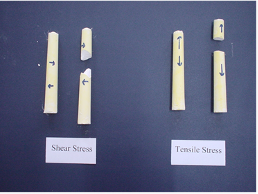

22.44. Tensile and shear stress with a piece of chalk#

Take a piece of chalk. Pull on the two sides, that creates tensile stress. The chalk breaks with a very nice flat break surface perpendicular to the length of the chalk. Now take another piece of chalk and twist the ends in opposite directions. We now have shear stress. The chalk breaks with a very different break surface. Try it, the effect is crystal clear and can be found Feynman’s Lectures of Physics II p39-9.

Fig. 22.16 The difference between tensile and shear stress#

22.45. Collisions and preventing damage: egg throw#

Anybody has a raw (unboiled) egg? Now this is something you might not have in a bare classroom, but then bring it from home. Have students hold up a towel, a coat, or any piece of textile, or the curtains of the classroom window. Then throw the egg full force into that. It will survive, it will not break. There are two principles at work. The force that decelerates the egg is spread over the surface of the egg, rather than applied at one point. Furthermore, the decelerating force is spread in time as the towel or curtain moves along with the egg. The spreading of forces also applies to seatbelts in cars and protective helmets, they spread the force over the body or over the head. Seatbelts also illustrate both the spreading in time and in area of the decelerating force as the belt is wide moves along with the body, thus lowering the force by spreading it in time and across a wide surface.

Fig. 22.17 Throw an unboiled egg without breaking it.#

22.46. Breaking or not? Protecting delicate objects#

Look around for something that can break if dropped on a stone floor. Then look for things that can prevent that using the two principles. For example, pillows, not part of a bare classroom, but perhaps available in the school. Or make a pile of some student coats or other clothing. There may be some foam somewhere. Then drop a glass or an egg. How are breakable objects usually packages in stores? Students will give examples and even may have some in their bags. How do girls make sure their cosmetic flasks do not break in their bags?

22.47. Bernoulli 1 with a piece of paper#

Hold a sheet of paper as shown in Fig. 22.17. The top end will be hanging down a bit. Blow across the paper. The top end will then move upward. A simple way of explaining is that you blow some of the air above the paper away, creating a pressure difference with lower pressure above the paper while having the normal atmospheric pressure below. A more correct explanation is that moving air has a lower pressure than air standing still. This pressure difference pushes the paper up. Instruments based on this principle are used to measure an airplane’s speed relative to the surrounding air.

Fig. 22.18 Bernoulli shown#

22.48. Bernoulli 2 with two leaves of paper#

(Before or after the previous demo) Continue the demonstration, tear another page from a student’s notebook, hold the two pages on the bottom end while the top ends of the paper are pointing parallel towards the students. Then ask students what will happen when you blow in between the pieces of paper and why. Then blow, the papers are moving towards each other rather than away from each other…..Bernoulli! Now of course you should have brought one of those toy helicopters to class as the climax to your Bernoulli demos. However, do not forget that it is not only the Bernoulli principle which makes airplanes fly, the reaction force on the wings due to downward deflection of air currents is a major force & .

22.49. Bernoulli 3 with straw and candle#

Light a candle. If I blow through a straw on the window side of the candle, will the flame move? Which way? Why? Answer: the flame will bend to the window side, the burning gases of the flame will point towards the area with lowest density/lowest pressure. In faster moving fluids the pressure is lower than in slower moving fluids (Bernoulli). For a younger audience: I blow some air away, the burning gas moves to the place with least air. For figures, see the chapter on Heat and Temperature.

Fig. 22.19 Bernoulli shown#

22.50. Energy conversions#

Drop anything and you get conversion from potential into kinetic energy, rub your hands (mechanical into thermal energy), clap your hands (mechanical into sound), point to the lights in the room (electrical energy into light and heat), etc.

22.51. Work and kinetic energy#

There are rulers with a gutter. Let a marble roll down and investigate the relationship between initial height of the marble and the displacement of the cup or wedge of carton. Using graph paper helps to get better measurements.

22.52. Asymmetry in properties, friction of human hair#

Ask a hair from a long-haired girl or propose that each student pair takes a hair from one of the two heads. Hold one end between thump and index finger of one hand, and slide with the other thump and index finger along the hair. Then slide in the other direction. It turns out that the friction of the hair is dependent on the direction of the sliding of thump/indexfinger!