19.10. A light bulb as hot as the sun?#

| Author: | Wim Sonneveld |

| Time: | 15-30 minutes |

| Age group: | From grade 10 |

| Concepts: | Inverse square law, radiation power, solar constant |

Introduction#

The power emitted by the sun can be reasonably well determined using a regular 100 W light bulb and the inverse square law.

Fig. 19.21 Feel with your hand at what distance the 100W lamp appears as hot as the sun.#

Equipment#

A 100 W light bulb with fitting and plug

Measuring tape

Blindfold

Optional for verifying the inverse square law: light sensor

Warning

Ensure that the blindfolded student is watched so that hands do not burn!

Preparation#

Preferably, wait for a bright, sunny day. Connect the light bulb to the power source.

Procedure#

Note

Step 2 of the procedure is only carried out if it is summer and sunny; otherwise, students must rely on their memory of the sun’s warmth on the beach (step 3). Work with groups of two students who come forward one by one. Student 1 performs the measurement and monitors blindfolded student 2 to ensure they do not burn their hand on the hot lamp. Emphasize this important task!

Ask students how to easily estimate the power of the sun. Partially answer this by turning on the 100 W lamp, holding your hand near it, and asking how powerful a lamp would need to be at 150 million km to achieve the same warming effect. Then explain the basic measurement method, including the inverse square law. Alternatively, you could let students partially figure out the inverse square law themselves in step 6. The inverse square law can also be verified with a light sensor (see Follow-up).

If it is summer and sunny: Student 2 holds their hand in the sun through an open window and feels how warm the sun is.

A blindfolded student 2 slowly moves their hand towards the 100 W light bulb until they feel the same warmth as when they held their hand in the sun on a sunny beach day (step 2). Student 1 ensures the hand does not touch the lamp and measures the distance from the hand to the (center of) the light bulb.

Repeat this for 6-10 pairs of students and determine the average distance. Meanwhile, other students can think about how to use this distance to calculate the sun’s power (see step 1).

Students calculate the ratio between the distance to the sun and the average distance to the lamp.

Students use the inverse square law or devise their own method to calculate the sun’s power based on the lamp’s power.

There is a way to improve the estimate. The hand primarily feels the infrared radiation. For the light bulb, this is 90-95% of the radiation. For the sun, it is 52% of the radiation. What correction must be applied to get a better estimate of the sun’s power?

Look up the sun’s power. Was our experimental estimate reasonable (within a factor of 10)?

Physics background#

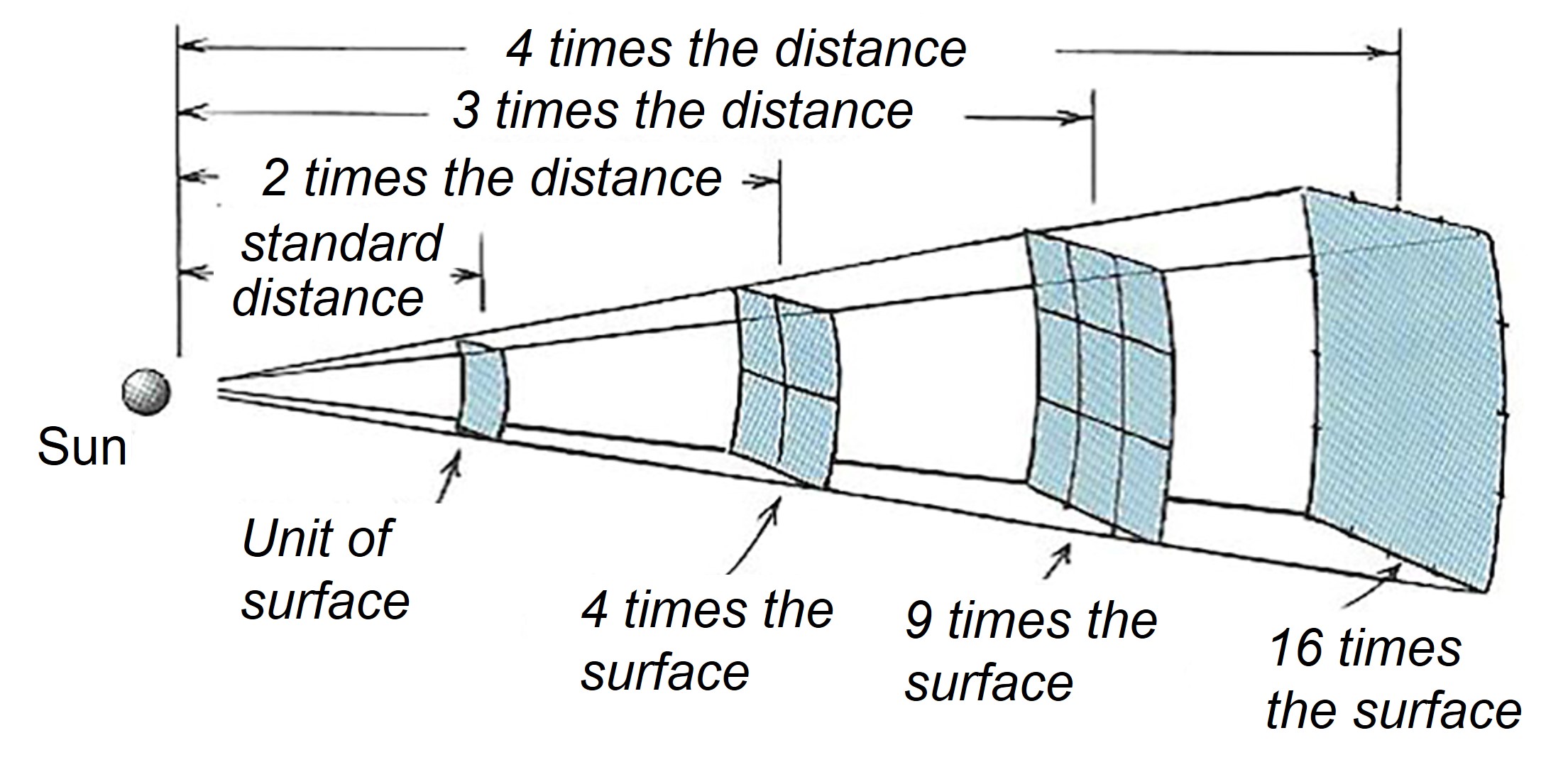

The essence of this experiment is that students calculate the sun’s emitted power by applying the inverse square law. The lamp emits 100 watts in all directions, with 90-95% in the form of infrared radiation. What falls on your hand is only a part of it. The same situation applies to the sun. We assume that the light bulb radiates its light and heat evenly in all directions, just as the sun radiates its energy in all directions. We also assume that the light bulb’s radiation is approximately similar to the sun’s radiation. The amount of energy captured by a given surface decreases with distance from the sun. The relationship with distance is that the energy through a surface, as shown in the figure, decreases with the square of the distance. This is known as the inverse square law.

Fig. 19.22 Inverse Square Law.#

Follow-up#

Before or after determining the sun’s emitted power, you can let students derive the inverse square law themselves. This can be done by measuring the light intensity of the light bulb at different distances with a light meter and graphing it as a function of distance on double-logarithmic paper. The inverse square law can then be applied again to calculate the solar constant, which is the solar power that reaches the earth on average per square meter. From this, you can also calculate the total solar power incident on the earth. This calculation shows that it is many times greater than the amount of power we, as earth inhabitants, use on average for transport, industry, lighting, heating, and other purposes! It is expected that total energy consumption in 2030 will be about \(700\cdot10^{18}\) J per year (source (Dutch): http://www.deconsult.nl). This observation can be used to motivate students to use and develop sustainable energy. For example, they can calculate how much total surface area of solar panels would be needed to generate that amount of energy as electrical energy (ignoring aspects like day/night, energy needs, transport of electrical energy, etc.).

For calculations, an Excel file is available [PFexcel.xlsx] Calculation of the sun’s power