14.3. Why does the water rise?#

| Author: | Peter Dekkers |

| Time: | 15-30 minutes |

| Age group: | Grade 10 and up |

| Concepts: | Heating and expansion of air, pressure, combustion |

Introduction#

Everyone knows that, when placing a glass over a burning candle, the candle extinguishes when oxygen in the glass runs out. If the candle is standing in a container with some liquid, the liquid is partially pulled up into the glass in the process. But is that the whole story? What exactly are you observing in this demonstration? Even when we’re all looking at the same event, we often see very different things.

What causes the liquid level in the glass to rise? People tend to come up with different plausible explanations. What are the arguments for and against each explanation? Do those arguments fit all observations?

Mere observation do not suffice to develop scientific insight, even less so when more than one explanation seems plausible. The result of research is often the conclusion that more research is needed. Sometimes even for an old and stale problem like this one… The teacher performs the experiment but is meant to mainly direct the discussion aimed at generating these insights about the nature of science.

Equipment#

Candle

Plate or saucer

Clear transparant drinking glass or jar

Some water

(optionally) coloring

Matches

Fig. 14.6 Place the glass or jar over the burning candle.#

Preparation#

Pour some water, if possible with coloring, into the plate, place the candle in the middle and light it. Have the glass ready. It must be large enough for it not to touch the candle or flame when placed over it.

Procedure#

A detailed scenario for a Predict-Observe-Explain approach for this demo can be found below. You will find there an outlined, hypothetical lesson plan, with suggestions for questions and assignments.

If you place the glass over the burning candle, it will extinguish after a while, causing the water level in the glass to rise. At least three explanations are plausible for explaining this:

The water takes the place of the oxygen that is consumed during combustion.

When the flame goes out, the temperature drops. According to the general gas law, the pressure and/or volume decrease. Atmospheric pressure pushes water inward until a new equilibrium is reached.

Water is formed in the flame, which precipitates when the flame goes out. Then the number of particles in the gas decreases, and therefore so does the pressure. The atmosphere pushes water inward until a new equilibrium is reached.

Let students brainstorm arguments for and against each explanation, exchange them, and come to a conclusion. The teacher can also ultimately contribute his or her own input.

Fig. 14.7 The candle is extinguished. What made the liquid level rise?#

Physics background#

For explanation 3: With complete combustion of candle wax (mainly paraffin or stearin), roughly speaking, for every two molecules of O\(_2\), one molecule of CO\(_2\) and two molecules of H\(_2\)O are formed. When the flame extinguishes, the temperature drops sharply in that area, and H\(_2\)O precipitates there. The pressure in the glass quickly drops, the atmosphere pushes water inward until equilibrium is reached.

For explanation 2: Heat released to the surroundings of the glass also causes pressure reduction according to the general gas law. However, this process is slow, while the liquid level rises noticeably quickly.

For explanation 1: For every oxygen molecule in the air, exactly one water molecule is formed. If that precipitates, the ‘resulting space’ can be filled by liquid. If we ignore the formation of CO\(_2\), then even explanation 1 (according to quite a few biology textbooks the ‘correct’ one) is somewhat true.

More important than the ‘correct’ explanation here is that students themselves come up with, defend, and evaluate arguments for and against the explanations. Another important aspect is that a need arises for empirical evidence.

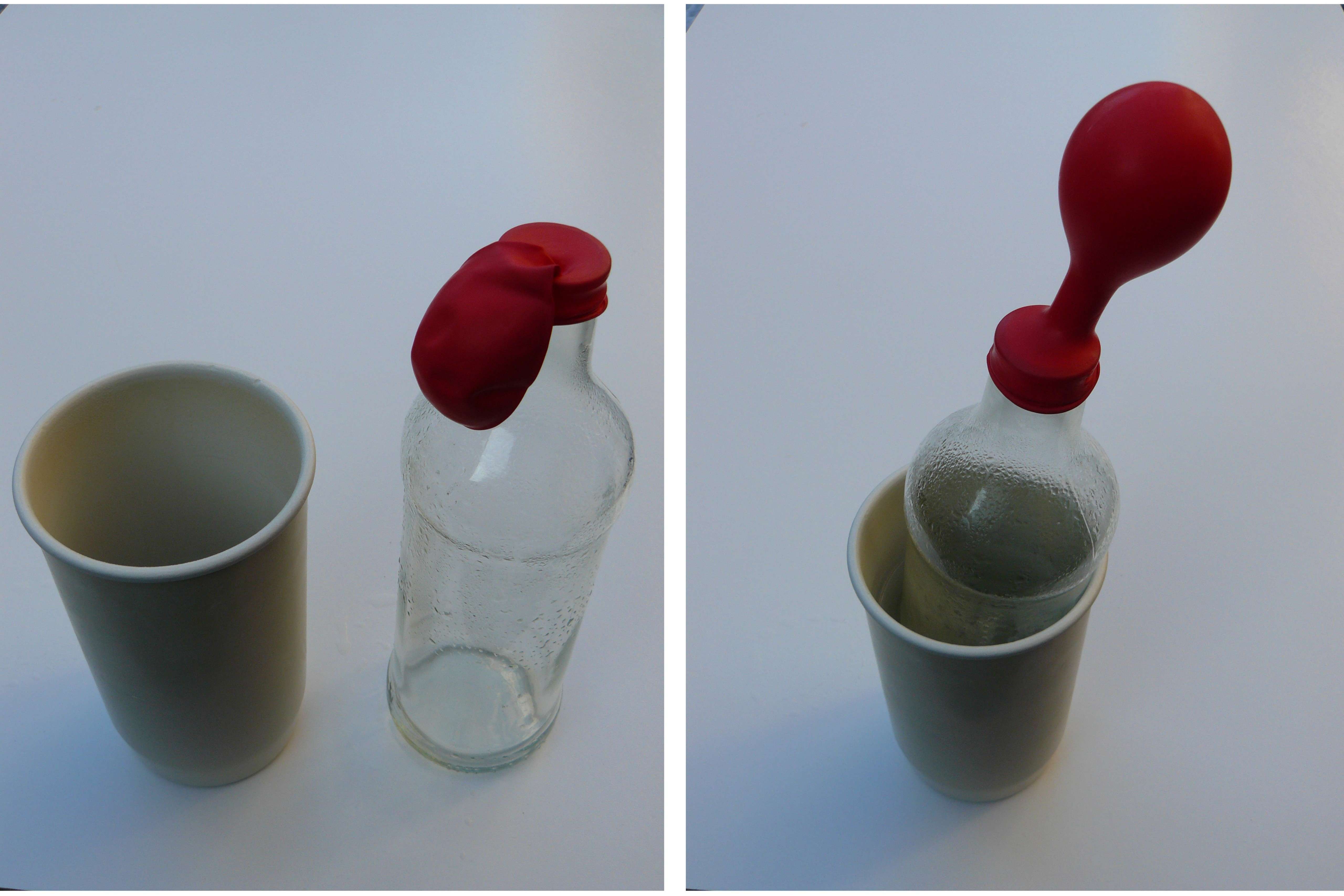

Fig. 14.8 The balloon on the bottle inflates when you place the bottle in hot water.#

Tip

Illustration of explanation 2: place an empty balloon over the opening of a bottle, and place it in a bowl of hot water [Liem, 1991]. Due to the heating of the air in the bottle, the balloon inflates, an illustration of Charles’s law (\(V/T = \text{constant}\) if \(p\) and \(N\) do not change).

Illustration of explanation 3: bring some water in an empty soda can to a boil, then quickly invert it and place it in a bowl of cold water, with the opening below the water surface. The can collapses with a bang because the water vapor condenses.

Follow-up#

With three candles instead of one, the final water level is higher [Liem, 1991]. Which of the explanations does this observation correspond to?

Warning

Hold the can in the illustration of explanation 3 with tongs or oven mitts.

References#

Worksheet#

Why Does the Water Rise?

Scenario for a POE Approach

Predict

Pour some (colored) water into the dish, place the candle in it, and light it. Get the glass ready. Explain that you are about to place the glass over the candle.

Ask for a prediction of what will happen. Even very young children know that the candle will go out after a while. Older students may also know that the liquid will rise in the glass.

(Ideally students’ predictions are partially, but not entirely, accurate. This way, the observation result is not discouraging, but there is still room for learning.)

Observe

Instruct the students to carefully observe what happens from the moment you place the glass over the candle, and to write down their observations as precisely as possible. Then place the glass and wait.

Afterward, compare the observations. Everyone will have seen that the candle goes out, and some will have noticed air bubbles escaping at the beginning. Usually, not everyone notices that the flame gradually gets smaller rather than going out suddenly. Almost everyone sees the water rising in the glass, but it’s not always apparent that this only starts in earnest once the flame is out. Some note that the wick smokes for a while after the flame is out, and a few even observe condensation on the glass.

It almost always turns out that not everyone sees exactly the same things. The teacher can point out that such differences are also very common among scientists and sometimes even necessary. This happens, for example, because they are interested in different aspects of the event: a biologist, chemist, or physicist might find different aspects of the extinguishing candle interesting.

Explain

The water replaces the oxygen consumed by combustion.

Students learn that oxygen is necessary for combustion. When the oxygen is depleted, the candle goes out. Some biology textbooks explain the rising liquid level in this experiment by saying that the water rises to replace the disappeared oxygen. The water often does indeed fill a part of the glass that roughly corresponds to the percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere according to Binas (a Dutch reference book): 21%.

But this is strange: according to chemistry, the oxygen atoms are all still there, just in different compounds than at the beginning. If there are still exactly the same number of atoms, how can there be room for the water to fill? What do the students think, is this explanation correct after all or can they think of an alternative?

So far, our audiences have forwarded the following three possible explanations (but there may be others);

The water replaces the oxygen consumed by combustion.

When the flame goes out, the temperature drops. According to the ideal gas law, the pressure and/or volume then decreases. Atmospheric pressure pushes water in until a new equilibrium is reached.

Gaseous water forms in the flame. When the flame goes out, the water condenses. This decreases the number of gas molecules, and thus the pressure. The atmosphere pushes water in until a new equilibrium is reached.

Have students choose the explanation they think is best and come up with arguments for their own explanation and against those of others. Arguments are more plausible if they fit better with known theory and observations. Based on these criteria, groups can compare their views.

In conclusion, the teacher may explain that it is not unusual for scientists to disagree. They can also find different observations important and accept different explanations. The smartest and most creative scientists find the best observations and arguments in favour of some claims (often their own) and against others (usually those of competitors). This has proven to be an excellent approach for the rapid development of reliable scientific knowledge.

Further options

To practice observing carefully, set up a webcam for the experiment and replay the events. Have students record their qualitative observations again and note the times. Build a description of events and times on the board. Subsequently, the discussion of explanations can always be linked to direct references to the observations. This raises the scientific level of the activities somewhat.

Instead of presenting students with possible explanations, you can also have them come up with explanations themselves and a practical way to test them. This will take (much) more time.

If you do this experiment with three candles instead of one, the final water level rises higher [Liem, 1991]. Which of the explanations does this observation agree with?

It might be worth considering placing sensors in the glass to record the temperature and pressure changes during the process, and using video measurement to establish the volume changes. This might quantitatively determine which form of the ideal gas law best describes this process. This has not (yet) been tested.