17.18. Rotating cubes#

| Author: | Karel Langendonck |

| Time: | 10-30 minutes |

| Age group: | Grade 10 and higher |

| Concepts: | Angular velocity, orbital velocity, centripetal force |

Introduction#

Students often find concepts linked to circular motion difficult. Examples include the difference between orbital velocity and angular velocity and understanding the centripetal force. In this demonstration, you combine these concepts with the frictional force to create a situation where only one force provides the centripetal force.

Equipment#

Turntable

Cubes of not too large mass (e.g. LEGO bricks or DUPLO dolls)

Scales

Ruler

Fig. 17.39 The turntable with LEGO bricks#

Preparation#

Place a cube on the turntable of a record player, as shown in Figure 17.39. LEGO bricks have been used as mass cubes in this setup. Determine the distance from the centre at which the cube will just slide when the turntable is turned on.

Procedure#

Place a cube at a not too large distance from the centre of the turntable and measure this distance \(r\).

Turn on the turntable. If all goes well, the cube will remain on the turntable.

Have students calculate the orbital velocity and angular velocity of the cube. Have them do this for both a turntable frequency of 33 rpm and 45 rpm.

Have students calculate the sliding friction force acting on the cube.

Stop the turntable again, place the cube slightly further from the centre of the turntable, measure the radius of the circular path again and turn the turntable on again.

Have students again calculate the orbital velocity, angular velocity and working sliding friction force.

Repeat the above step as many times as necessary until the point is reached at which the cube swings off the turntable. At that point, the point is reached where the maximum sliding friction force on the cube is an issue. You can now calculate (or have calculated) the maximum value for the static coefficient of friction (and hence the dynamic coefficient of friction).

A question to check students understanding: Can you get a coefficient of friction greater than 1?

Fig. 17.40 A variation of the demo using a tuneable turntable.#

Physics background#

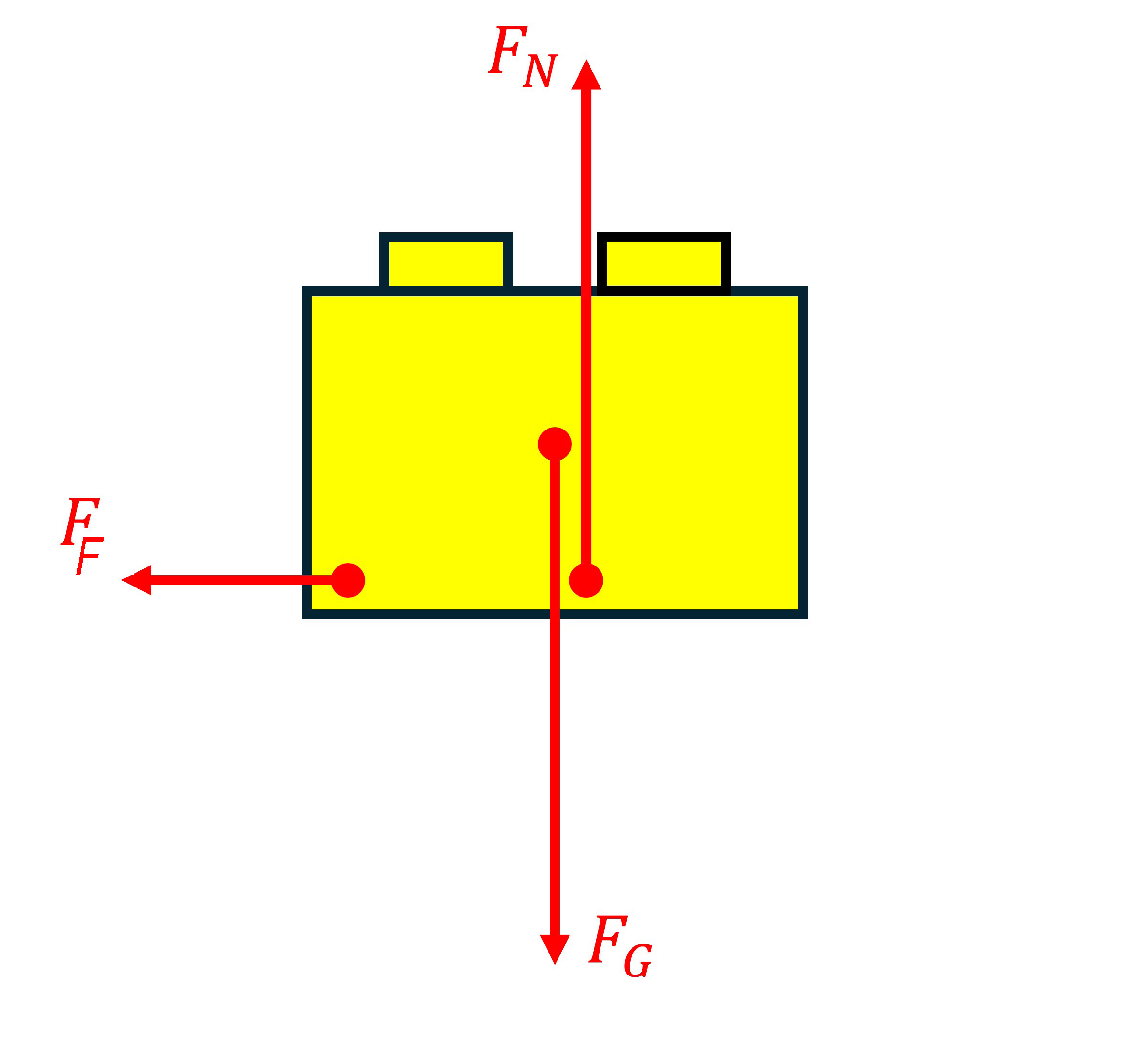

Three forces act on the cube (see Figure 17.41): the gravitational force \(F_G\), the normal force \(F_N\) and the shear friction force \(F_F\). At the moment the cube is on the turntable of the record player, it is the sliding friction force that provides the centripetal force. The following then applies:

In this equation, \(F_F\) represents the friction force (in N), \(F_c\) represents the centripetal force (in N), \(m\) is the mass of the block (in kg), \(v\) is the tangential velocity of the block (in m/s), and \(r\) is the radius of the circular path (in m).

Fig. 17.41 Three forces on the cube#

The friction force can also be calculated by multiplying the normal force on the block by the static friction coefficient. The normal force is, of course, equal to the gravitational force. In formula form, this yields:

\(F_F = \mu _s \cdot F_N = \mu _s \cdot m g\)

In this formula, \(F_F\) again represents the kinetic friction force (in N), is the static friction coefficient, \(F_N\) represents the normal force (in N), \(m\) is the mass of the block (in kg), and g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s\(^2\)).

By combining both expressions for the kinetic friction force, you can derive a formula for the static friction coefficient for this situation:

In the above expression, you can also substitute the formula for the tangential velocity (\(v = \frac{2 \pi r}{T}\), with \(T\) being the period (in s)). This gives:

From this expression, the directly proportional relationship between the static friction coefficient and the radius of the circular path can be recognized. At the point where the block is flung off the turntable, the maximum value for the static friction coefficient has been reached.

Tip

A few testers reported that the turntable was not smooth enough. Without a rubber mat or with a plastic cover around the mat or smeared with oil, it went well.

This experiment is not very exciting in its execution, so it is important to involve the students well in the execution and collection of the measurement results. You can then let the students calculate some things in between.

Calculating the orbital period of the cube (and thus the orbital and angular velocity) will not be as simple and logical for all pupils. Pay explicit attention to this.

Further investigation#

In the experiment, you can vary the orbital time (where a frequency of 78 rpm is also possible on certain types of turntables), the mass of the cube and the type of surface of the cube and/or turntable. This allows experimentation with a diversity of variables, which also makes the experiment suitable as a practical for students. One of the testers reports: On the same radius, you can apply different masses and compare whether the mass makes a difference. Is a larger mass more likely to be thrown off the turntable?