12. Predict Explain Observe Explain#

In many phenomena, students and laypeople come up with predictions in which they have a lot of confidence, that yet turn out to be wrong. Our intuition is often off the mark. It is precisely in these cases that demonstrations can be extra motivating and useful. But then it all comes down to the proper approach and your role as a teacher. You must optimally emphasize the contrast between prediction and outcome and try to stimulate the thinking of all students instead of that of just a few smart ones.

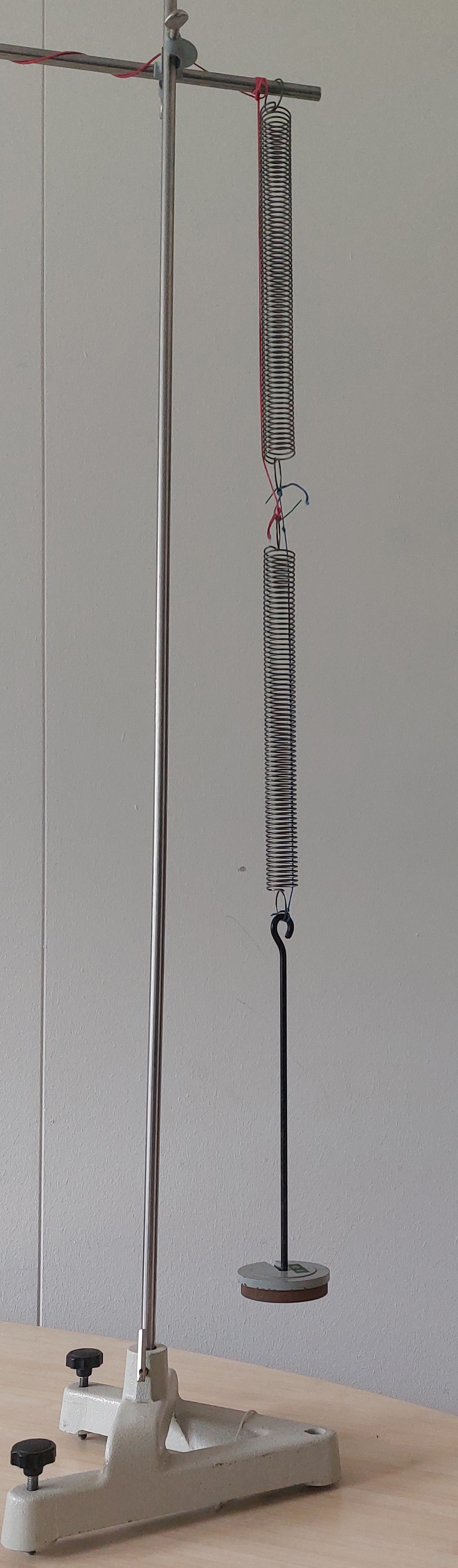

Fig. 12.1 What happens to the block when the hook is cut with pliers?#

The idea is that students first predict what will happen and explain, at least to themselves, why they think it will happen in that particular way. This first step includes both the prediction and an explanation, emphasizing that we ask students for a prediction with reasoning, not just a guess. This step encourages students to draw on their prior knowledge and understanding of physical concepts to anticipate what will happen. Predicting first will encourage students also to observe more carefully. They become aware of their own ‘preconceptions’. Moreover, writing down their prediction may motivate them to want to know the answer, and an explanation of why they think the demonstration will happen in a certain way provides valuable insights in their thinking.

Note

A great example of the importance of making a prediction is found in Two springs, series or parallel? Students there predict what happens to the block when the hook is cut with pliers. They have sufficient knowledge of springs to make a considered choice, but will probably still be surprised by the result.

The demonstration is then performed by the teacher. A demonstration is often well suited as it reduces distracting elements, for instance handling the equipment, observing what happens and simultaneously making sense of it. During this phase, students gather empirical evidence that either supports or contradicts their initial predictions.

In the final step, students are asked to explain the observed results and compare the outcome with their initial prediction. This step involves thus critical thinking and reasoning. Through guided discussion and reflection, students develop a deeper understanding of the underlying physics concepts.

A great example is found in the demonstration Twice as much isn’t twice as big where the idea of More of A results in more of B is dispelled. Especially explaining why (surprisingly) nothing changes is important in that demonstration.

Tip

An excellent example of a POE-approach is presented in Rich boiling phenomena, including a table which scaffolds the process.

These steps are further elaborated on in the table below We use the trivial example of a large and small falling stone (Figure 12.2). (Both the mass and the volume of the stones are different). Many students (and their parents) expect a large stone to fall faster than a small one.

Fig. 12.2 The steps of PEOE are explain using this simple demonstration.#

Step |

PEOE |

Example |

|---|---|---|

1 |

Show how you will perform the experiment or ask “how can I investigate whether…?”. Then come up with a plan for the demonstration with the students and make sure it is clear to all students before they start predicting. |

I (teacher) have two stones, a large and a small one. How can I investigate which one falls faster? |

2 |

Predict – Explain: Let students individually write down their expectation (predict what will happen) and the reason for it. This can be done in their notebooks or on a special worksheet. Alternatively ask multiple-choice questions in e.g. Socrative or Plickers. |

I will let the stones fall simultaneously by pulling my hand downward (see Figure 12.2). Write down which stone will hit the ground first. Explain why you think so. |

3 |

A short inventory of expectations. It is most important that students realize there are different predictions, usually all with ‘reasonable’ arguments. Because everyone has written down a prediction with a reason (or has voted on Socrative), any student can be randomly asked to contribute to the discussion instead of only volunteers. |

Inventory of reasons for the three possible predictions (large or small stone or equal). Results of the vote and possibly arguments noted on the board. |

4 |

Observe: Have each student write down their own observation before discussion begins. If this part is skipped, students will ‘adjust’ their observations as soon as the discussion starts, and differences in observation will become vague. It is usually possible to repeat the experiment until there is consensus about the observation or measurement. |

The teacher stands on the table with the two stones and lets them fall onto the table surface or onto a plank on the ground that makes a clear noise. Everyone listens to the result. Repeat until everyone agrees on the result. |

5 |

Explain: Ask students to discuss (think-pair-share) the explanation for the observation or measurement. In the subsequent class discussion (step 6), each student can again be asked to contribute. |

Think-share-exchange ideas about whether size has anything to do with fall speed. |

6 |

Class discussion. |

Class discussion and conclusion that size apparently does not matter. However also address: Are there examples of objects that do not hit the ground at the same time? |

7 |

Noting the complete explanation on the board or referencing the notebook. |

|

8 |

Are there other similar phenomena that we can now also explain? Continue the demonstration with objects where air resistance plays a role, for example, first an A4 paper, then a crumpled ball, then placing the A4 sheet on top of a book and letting them fall together. |

In most PEOEs, step 7 concludes the activity. With falling objects, you ought to also investigate the role of friction as indicated in step 8.

12.1. All Students#

An important aspect of this approach is the involvement of ALL students. They should individually formulate their expectations/predictions on paper with a rationale. All students then observe the result of the demonstration. All are involved in resolving the difference between prediction and observation. This approach is, with an emphasis on comparing and contrasting prediction and observation, can only be requested in demonstrations where students themselves have some prior knowledge and can be expected to think they know what will happen. The PEOE model is not suitable in every demonstration.

To get attention for the actual demonstration, make sure that students are aware of their own expectations/predictions and those of the others. Writing down the prediction and an accompanying rationale leads to more engagement. The common practice of just asking what the class thinks and letting a single smart student answer is not effective. Asking all students for the reasoning behind their prediction also provides the teacher with insight into students’ thought processes. Important is that students notice that different thoughts exist about the phenomenon; that there are conflicting predictions and different ideas about the phenomenon. This generates motivation to find out how things really are. It helps students evaluate their own learning and construct new ideas.

Mitchell and Mitchell [1992] give the following advice based on his extensive PEOE experience:

It is very important that students realize that they are not alone in their prediction. Therefore, it is important to summarize the class’s ideas and report back to the class (see for instance Falling candle). An effective way to do this is to have predictions written down in a handy format so that the teacher can quickly take inventory by walking around.

Students must feel safe to give their opinion. Therefore, never link assessment to a PEOE, not even by praise for a correct answer. Emphasize to students that you are interested in their ideas and that both wrong and correct predictions are important for the class reasoning process and for their own learning process.

A discussion after the prediction where different predictions are explained and discussed often works well. This discussion precedes the observation, the execution of the demonstration itself.

At the end of PEOE, emphasize that incorrect predictions are often quite understandable or even ‘logical’ and that they are very useful in the learning process.

See White and Gunstone [2014] for a very complete description of the pedagogy. Google with ‘POE’ and ‘physics demonstrations’ as search terms to find examples. Liem [1991] “Invitations to Science Inquiry” contains over 400 demonstrations with surprising outcomes for students. In this book you will find many demonstrations where the PEOE approach is used and the steps have been made explicit, for instance in our demonstration Why does the water rise?.