11. Thinking-Back-and-Forth#

In all natural sciences, describing and explaining phenomena is key. A scientific description of a phenomenon evolves from everyday language to professional language, and from an arrangement of concepts into a coherent theory or model. These models and theories (in the world of ideas) allow us to develop hypotheses and predictions that can be tested by going back to the phenomenon (in the world of observations). When returning to the world of observations, our ‘improved’ theoretical understanding allows us to see more than we did when first observing the phenomenon. With ‘new’ observations come new questions, and so our understanding of the natural world develops in a process of observing, reflecting/questioning, and experimenting. This iterative and dynamic process of thinking-back-and-forth (TBF) [Spaan et al., 2022] between the empirical and the theory at each step of the process is a more accurate description of science than describing the scientific method as a linear process, from research question to experiment to conclusion.

11.1. World of ideas and observations#

Fig. 11.1 Liquid column of ‘stacked’ liquids as shown in Playing with density.#

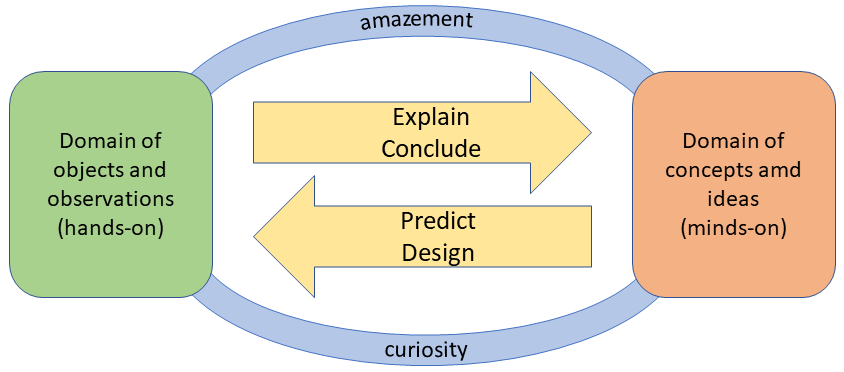

To define thinking-back-and-forth (TBF) properly, we distinguish between the domain of phenomena, objects and observations (’hands-on’) and the domain of concepts and ideas (’minds-on’), see Figure 11.2. A TBF activity links these two domains, it is an activity in which a line of reasoning or argument is constructed in which a hands-on aspect is linked to a minds-on aspect. As an example, we consider a demonstration in which the teacher creates a column of “stacked” liquids of different densities, in which some objects are situated at the boundary planes, see Figure 11.1. Present in the domain of phenomena, objects and observations are observations such as the stratification of liquids and the exact location of objects in the liquids. In the domain of concepts and ideas are underlying concepts such as volume, mass, density and buoyancy. When you formulate a line of reasoning like “the object is at the interface of water and oil so the density of the object is in between that of oil and water,” you are engaged in TBF.

Fig. 11.2 In the domain of objects and observations, we observe and measure. In the domain of concepts and ideas, we try to reason with theories about how they are interrelated. Between those two domains we can think back-and-forth, identifying four kinds of activity.#

TBF is shown schematically in Figure 11.2. On the left is the world of phenomena in which we make observations and take measurements. On the right is the world of concepts and ideas in which we reason with concepts and models. The connecting arrows display the four different types (explaining, concluding, predicting and designing). Explaining and concluding include activities in which the students move from the world of observations (phenomena) to the world of ideas (theory and models). In predicting, the direction is reversed and theory is used to make statements about phenomena and measurements. We design experiments to test these predictions.

Demonstrations are ideally suited to develop conceptual knowledge using TBF. As the teacher is (much) more skilled in the hands-on aspects such as manipulating the equipment, distracting ‘noise’ [] is reduced. With the help of the teacher, using interactive discussions, students can connect the world of phenomena with the world of ideas. A great example of this can be found in the demonstration Speed of light in a liquid.

When explaining, students search for a natural-science-based explanation for an observation or describe that observation using scientific terms. Instead of having students formulate their own explanation, concept cartoons [Naylor and Keogh, 2013] provide an opportunity for students to select a given explanation. Demonstrations in which explaining plays a major role include Blowing out a light bulb, Boiling by cooling, Shadow of a flame and Mysterious fountain.

Concluding often comes down to finding a general rule or determining some value that cannot be measured directly, such as the gravitational acceleration. Usually the general rule has the form of a mathematical relationship. Statements about a property of an object or substance are also part of drawing conclusions, such as whether or not an electric current is flowing. A conclusion is complete only if it is substantiated, which requires additional TBF. This becomes clear in, for example, Measuring ‘stars’. Reflecting on the accuracy of a determination occurs in Determining g using a concept cartoon. Other demonstrations focusing on drawing conclusions include Physics of the panflute and Standing waves with an electric toothbrush.

Prediction involves predictions of observations on the basis of (perceived) knowledge, it includes substantiation and is not meant to be a blind guess. Substantiation may be based in legitimate physics prior knowledge, but also in popular misconceptions based on “alternative theories.” Prediction combines well with explanation. Examples of demonstrations that include predicting are Investigating a devastating flame, Up and down the hill, Cooling of metal spheres and Upward and downward force.

Designing includes the designing of an experiment as part of research, as well as engineering design. Although design is not usually the focus of demonstrations, aspects of it can be addressed with a question such as “If I want to achieve …, what should I change about the setup?”. This plays out in Lorentz force on charged particles and Crookes’ radiometer.

11.2. Stimulation of TBF#

Once students link theories and concepts to observable phenomena, new questions arise that provide an opportunity to further stimulate thinking-back-and-forth. Sometimes it suffices to challenge students to formulate the research question precisely in terms of the physics language they have learned, thus highlighting the central importance of using correct language. As an example, consider a demonstration in which a large and a small stone are released and hit the ground at the same time. Would it make any difference if a very small stone was used? Would we get the same observation if they were dropped from a greater height? What would happen if a feather was attached to one of the stones? If students are challenged to formulate these questions in terms of physics concepts they can be expected to start using terms encountered previously such as air friction, gravity and possibly inertia. Using correct scientific language is essential because you cannot obtain a scientifically answerable question without it.

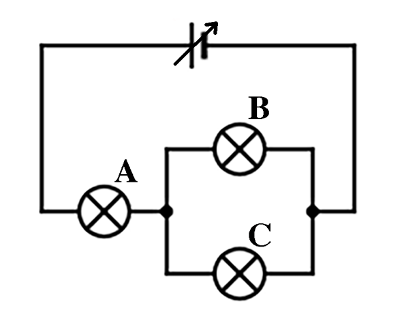

Often several pedagogical pathways are available to engage students in thinking-back-and-forth. The teacher chooses in advance which thinking-back-and-forth -tasks the students will undertake and which ones will not be included this time. As a example, we will look at a PEOE demonstration of an electrical mixed circuit, see Figure 11.3.

Fig. 11.3 Mixed circuit. Explaining what happens with the brightness of the lamps if one is unscrewed requires a lot of TBF.#

As a teacher you may elect to focus on the concepts of (replacement) resistance and current flow via predicting and explaining. The starting question could be What happens to the brightness of bulbs B and C if bulb A is unscrewed? You may help students through asking multiple-choice questions. After a brief exchange of answers and arguments, you as the teacher unscrew bulb A. Bulb B and C appear to be turned off. The explanation is sought in class and linked to the concepts resistance (which becomes very large) and current (which becomes zero). You now tighten bulb A again and ask what happens to the brightness of bulbs A and C when bulb B is unscrewed. The students should now be asked to formulate their answer and justify it. Again there is an exchange of ideas before you actually unscrew bulb B. Then the assignment is for students in pairs to figure out what was wrong with their previously given incorrect explanations (which are very likely to occur) and ultimately find the correct explanation. Doing the explanation task in this way will produce strong ack-and-forth thinking. It is important that you as a teacher finalize by relating the concepts of (replacement) resistance and current correctly to the explanation.

With a different approach and through other TBF activities, further concepts may be developed. For example, draw circuit diagrams using clearly visible wires (use a camera!). Then let students think back and forth between the abstract representation of the circuit diagram and the built circuit actually on the table. Yet another way in would be to ask students what in the circuit would have to be changed in order for all three bulbs to light up with the appropriate brightness without adding any other bulb. This would be a design activity. Possibilities abound. Our job as teachers is to make an optimally appropriate selection from these and develop conceptual understanding as best we can!

How do we bring thinking-back-and-forth into the pedagogy of demonstrations

One way to do so is by a solid preparation of the demonstration:

List the phenomena that are observable in the demonstration.

List the concepts associated with these phenomena. Which of these concepts fit the learning objectives of your activity?

Steps 1 and 2 are best carried out while you yourself are building the setup.Maintain focus. Which phenomena merely distract from the goal and create noise? Furthermore, which concepts will you want to avoid to prevent distracting ‘noise’?

Devise a stepwise plan for the demonstration with explicit attention for the back-and-forth thinking questions you will ask and the assignments you will give.

See Force and motion with a bowling ball and Lorentz force on charged particles for worked out examples of the stepwise plan.

11.3. References#

Stuart Naylor and Brenda Keogh. Concept cartoons: what have we learnt? Journal of Turkish Science Education, 10(1):3–11, 2013.

Wouter Spaan, Ron Oostdam, Jaap Schuitema, and Monique Pijls. Analysing teacher behaviour in synthesizing hands-on and minds-on during practical work. Research in Science & Technological Education, pages 1–18, 2022. doi:10.1080/02635143.2022.2098265.