20. 4-Momentum & \(E=mc^2\)#

20.1. Proper time#

We have seen that in Special Relativity events are described by four coordinates: \((ct,x,y,z)\). Moreover, distance is measured via a inner product \(A^\mu \cdot B^\mu = A^0B^0 - A^1B^1 - A^2B^2 - A^3 B^3\). That opens the question: what about other quantities that we use in mechanics.

If position is \(X^\mu = (ct,x,y,z)\) then what is velocity? Is \(v^\mu \equiv \frac{dX^\mu}{dt}\) a good choice? It is what we are used to: velocity is change in position over time. However, we need to be careful. We require that our quantities are four-vectors, i.e. they transform according to the Lorentz Transformation. And the length, i.e. the inner product with itself, is the same for all inertial observes.

However, in our our first choice of the definition, we take the derivative with respect to time. But time is not the same for different observers!

We do know that the distance \(ds^2\) is LT invariant, as is \(c^2\), therefore we can combine both into another invariant - of time

If we spell out \(ds^2\) we can write

\(d\tau\) is called proper time or Eigenzeit because for the rest frame \((dx=dy=dz=0)\) we have

For a particle moving with 3-velocity \(\vec{u}=(u_x,u_y,u_z)=(\frac{dx}{dt}, \frac{dy}{dt}, \frac{dz}{dt})\) we can relate the proper time \(d\tau\) to the frame/coordinate time \(dt\) as

Here, we identify the magnitude of the 3-velocity \(u\). In other words

The proper time interval relates to the frame time via the \(\gamma\)-factor for the velocity \(u\).

20.2. 4-velocity#

Now we can tackle the 4-velocity. In other words: to make any sense we must define a velocity whose length is an invariant. Furthermore, velocity must be something like displacement over time interval. For the displacement the obvious choice is: \(dX^\mu\), i.e. a particle has moved from \(X^\mu\) to \(X^\mu + dX^\mu\). The displacement \(dX^\mu\) transforms, of course, via the Lorentz Transformation. Moreover, its length is a Lorentz Invariant. In order to arrive at an adequate velocity, we must thus divide the displacement by a time interval that is also a Lorentz Invariant. Luckily, we have just seen that proper time is a Lorentz Invariant.

Therefore, the 4-velocity \(\vec{U}\) is

where the derivative of the 4-position vector is taken with respect to the proper time \(\tau\). We obtain the relation to the 3-velocity \(\vec{u}\) just from filling in \(d\tau = dt/\gamma(u)\)

4-velocity transfers between frames moving with speed \(V\) as given by the 4-vector transformation as \(\vec{U}\) is a 4-vector.

20.2.1. Be careful with 4-vector interpretation#

We compute the inner product of \(\vec{U}\) with itself \(U^2 = \gamma^2(u) (c^2-u^2)\). That is a LT invariant of course. Therefore, we choose the frame such that \(u=0\), or in other words \(U^2=c^2\). The 4-velocity length is constant! That is not intuitive at all. Even stranger as the vector has constant length, it follows that the 4-velocity is always perpendicular to the 4-acceleration.

The counter intuitive stuff happens of course due to the pseudo-Euclidean metric.

20.2.2. Revisit 3-velocity transformation#

Earlier we transformed the velocity \(u\) of a particle in \(S\) to \(S'\) which was moving with \(V\). This was quite complicated and the formula is difficult to remember. However, there is no need to remember the formula, you can always derive it from the transformation of the 4-velocity.

For the 4-velocity \(\vec{U}=(\gamma(u)c,\gamma(u)\vec{u})\) we can write down the LT of a 4-vector between \(S\) and \(S'\).

If we now divide the second of these equations by the first we obtain

and if we divide the third of these equations by the first we obtain

Just what we have derived before, but now in a way that you can always do this on the spot if you know the definition of the 4-velocity and the LT of a 4-vector.

20.3. 4-momentum#

If we postulate that the mass \(m\) is LT invariant we can define the 4-momentum simply by

with the 3-momentum \(\vec{p}=m\gamma(u)\vec{u}=m\frac{d\vec{x}}{d\tau}\).

!!! warning “mass is a LT invariant”

The mass \(m\) does not change as a function of velocity \(\vec{u}\). You still sometimes see \(\tilde{m}\equiv\gamma(u)m\) and with this \(\vec{P}=(\tilde{m}c,\tilde{m}\vec{u})\). That is not practical as it mixes kinetic energy with inertial mass.

20.3.1. Conservation of 4-momentum#

For collisions now the total 4-momentum is conserved (per component)

If the total momentum is conserved than this must hold for the components \((m\gamma (u)c,\vec{p})\).

Note, that we did not write “mass is conserved”. We postulate that it is a LT invariant, that is: it is the same for all inertial observers. But that does not imply that for collisions the mass should equal before and after the collision.

20.4. E=mc²#

The most famous equation in physics.

We will derive it by looking at N2 in its relativistic form.

Kinetic energy was defined as work done on a mass. We again start from that and fill in N2 and take it step by step

This integration is more difficult than what we had before as the \(\gamma(u)\) factor appears additional in the differential (for small velocities we have \(\gamma(u)=1\) and we just get \(\frac{1}{2}mu^2\) as before). Now we apply integration by parts

Integration by parts

Easy to remember integration by parts formula, from the product rule

Here we used \(f'=d\gamma(u)\vec{u}\) and \(g=\vec{u}\).)

If we now inspect the limiting cases for the velocity

particle at rest: \(u=0 \Rightarrow \gamma (u)=1 \Rightarrow \Delta E_{kin}=0\)

small velocity \(\frac{u}{c}\ll 1 \Rightarrow \gamma (u)=1+\frac{1}{2}\frac{u^2}{c^2}+{\cal{O}}(\frac{u^4}{c^4}) \Rightarrow \Delta E_{kin}=\frac{1}{2}mu^2\)

The limiting cases work out. Very reassuring.

We can add a constant (LT invariant) to the kinetic energy \(E=E_{kin}+mc^2 = m\gamma(u)c^2\). Adding constants to the energy/potential is always allowed as only the change of it is physically relevant (or the relative energies). The reason for this constant will become apparent below as this allows to include the energy in 4-momentum nicely.

We obtain

or in the rest frame \((u=0 \Rightarrow \gamma(u)=1)\)

With this energy \(E=m\gamma(u)c^2\) we can define the 4-momentum as follows (we had \(\vec{P}=(m\gamma(u)c,\vec{p})\))

4-momentum with a different energy?

With a different energy (addition of another constant to \(E_{kin}\) than what we did above) the length of the 4-momentum would not be LT invariant and \(\vec{P}\) not a 4-vector. If we would have used \(E=mc^2(\gamma -1)\) then \(P^2\) would not be LT invariant. You see this by computing \(P^2=\frac{E^2_{kin}}{c^2}-p^2c^2=m^2c^2(2-2\gamma)\).

And we have finally derived the most famous equation in physics. We will use, however, \(E=m\gamma(u)c^2\) mostly exclusive as we are not always in the rest frame. The equation says essentially that mass is the same as energy. They are different manifestations of the same thing. A particle has energy in itself at rest without being in any potential.

NB: As gravitation acts on mass, it should also act on energy if they are the same! This is indeed the case, also photons, massless particles, feel gravity. More about that in Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

20.4.1. Mass in units of energy#

The mass of an electron \(m_e = 9.13\cdot 10^{-31}\) kg is often given as \(512\) keV, [kilo electron Volts]. Mass of all elementary particles is given actually in units of eV.

One electron volt is

The conversion to mass via \(E=mc^2\)

20.4.2. The fame#

The origin of the fame is probably twofold.

Firstly, mass is no longer conversed as was a central pillar in Newton’s mechanics. It can be converted. This was shocking for physicists only.

Secondly, when mass is actually converted into energy e.g. in a nuclear fission bomb or inside the sun with nuclear fusion, the effect is immense. The drop of the two nuclear bombs (little boy and fat man) on Hiroshima and Nagasaki made the equation inglorious world-known; life changing for all people.

Einstein’s rock star status helped certainly quite a bit.

20.5. Energy-momentum relation#

The 4-momentum is, of course, a 4-vector and therefore \(P^2\) is LT invariant. Let us have a look at the outcome with \(\vec{P}=\left ( \frac{E}{c},\vec{p} \right )\)

Indeed, we find that \(P^2\) is LT invariant as \(m\) and \(c\) are LT invariants. Rearranging the equation, we obtain

This converts back to \(E=mc^2\) in the rest frame.

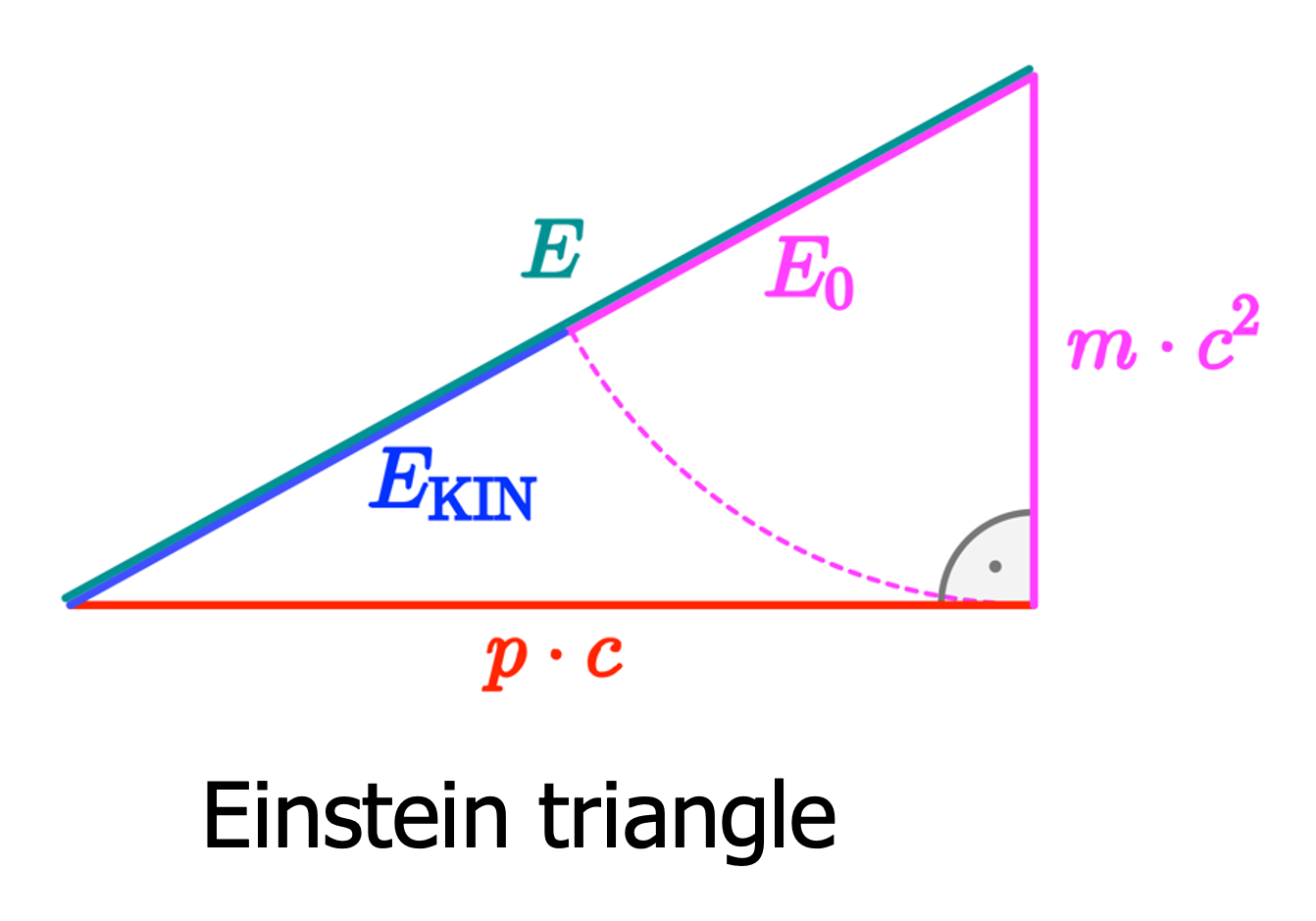

Fig. 20.1 Einstein Triangle. From Wikipedia Commons, public domain.#

You can visualize the energy momentum relation with the Einstein triangle shown here, as the relation has the form of \(c^2=a^2+b^2\). With the kinetic energy as \(E_{kin}=mc^2(\gamma(u)-1)\). \(E=E_0+E_{kin}\equiv mc^2 +E_{kin}\).

20.5.1. LT invariance of P²#

Above we found a very useful, but bit hidden relation in the derivation

This is of course LT invariant, as \(m\) and \(c\) are LT invariants (and the momentum is a 4-vector), but more importantly we can use this for computations of relativistic collisions. By the conservation of 4-momentum we can of course compute all collisions by equating the 4 components of the momentum before and after the collision. It is often, however, mathematically easier to write down the conservation of momentum and then square it. Because you can write down \(P^2=m^2c^2\) directly, this saves often computations.

20.6. Photons#

For photons we have the energy given by \(E= \hbar \omega\) and the momentum as \(p= \frac{\hbar\omega}{c}\). The 4-momentum of a photon is

It is directly clear that for photons the LT invariant \(P^2=0\).

We could substitute the photon 4-momentum into the energy-momentum relation, we find

This seems to confirm that photons do not have mass. But we need to be careful: photons do not have a 4-momentum of the form \(P^\mu = ( m\gamma c, m\gamma u)\). They can’t: (1) their velocity is always c, which would lead to \(\infty\) for their \(\gamma (c)\), (2) with a mass \(m=0\) we multiply \(\gamma c\) by zero. Together, this would gives us \(0 \times \infty\) which is not defined in a unique way.

Thus: photons do not have mass. Do not get confused with \(E=mc^2\).

20.6.1. Rest frame of a photon?#

Does a photon have a rest frame? It travels with the speed of light \(c\) (obviously) in all frames.

The answers is no and we give three good arguments.

A rest frame implies that in this frame the object is at rest. But for a photon, traveling at \(c\), which is LT invariant, there is no frame at which it is at rest, but only frames in which \(v=c\).

The proper time of a photon is \(d\tau^2 = dt^2 -\frac{1}{c^2}d\vec{x}^2\) but this is always equal to 0! A photon does not experience the passage of time, therefore it is reasonable to state that do not have a rest frame.

In the hypothetical rest frame for a photon there would be no electro-magnetic radiation/interaction possible. In this frame e.g. the interaction between electrons would be zero.

20.6.2. Doppler revisited#

In chapter 18 we discussed the Doppler effect from a relativistic point of view. With the concept of 4-momentum it is easy to derive the Doppler shift of photons as observed in different frames of reference. We take the usual LT between \(S'\) and \(S\). In \(S\)’ a photon is moving along the \(x'\)-direction. It has frequency \(f'\). Its 4-momentum is

The \(\pm\)-sign indicates the direction of the photon: + for moving in the positive \(x'\)-direction, - for moving in the negative \(x'\)-direction.

Using the Lorentz Transformation, we can easily transform the 4-momentum to the frame of \(S\):

Note that we didn’t use the transformation of \(P'^1_{photon}\) as this will give the same result.

20.7. Speed of light as limiting velocity#

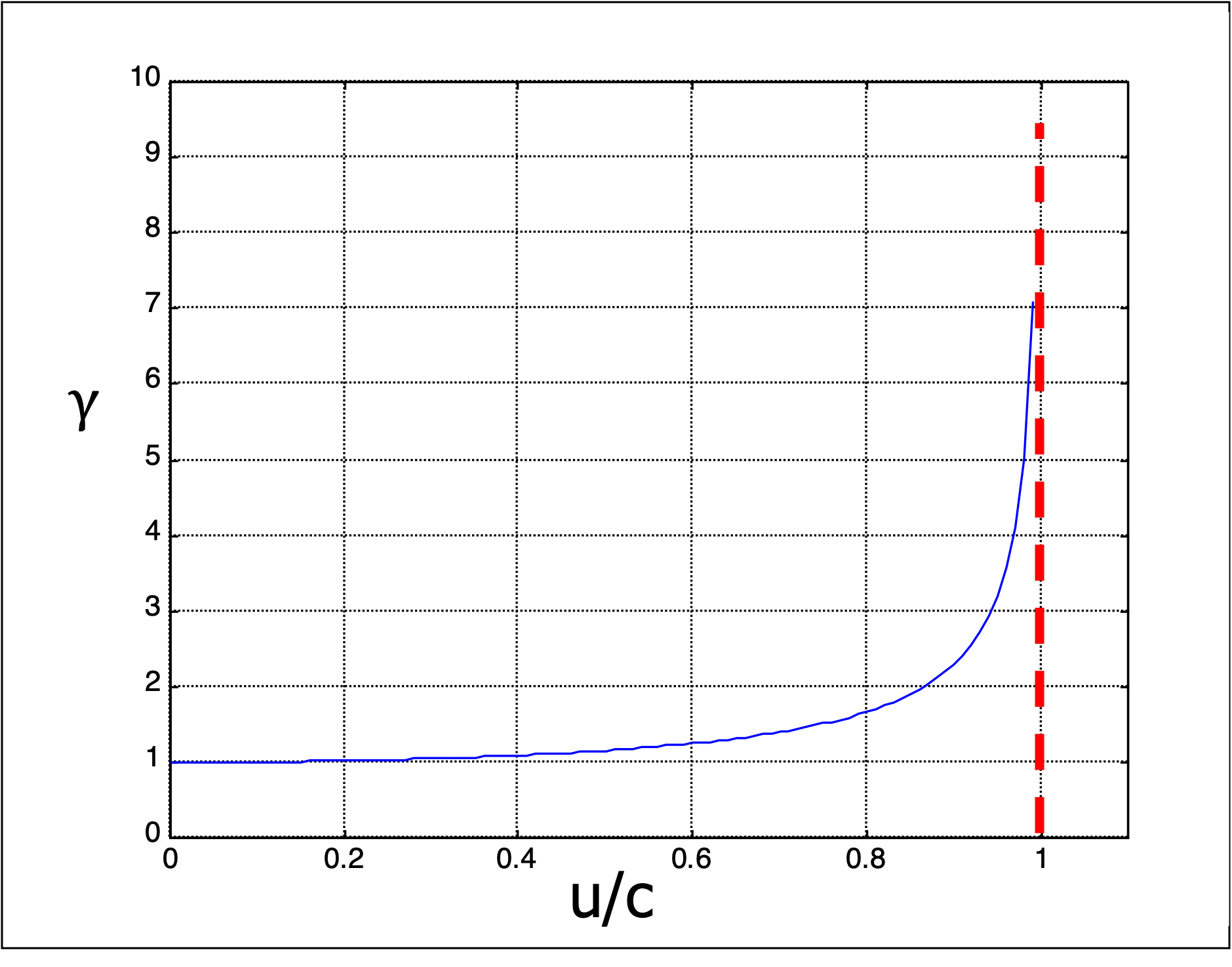

The \(\gamma\) factor increases strongly if the speed approaches the speed of light \(u/c\to 1\) as can be seen in this plot

Fig. 20.2 Lorentz factor \(\gamma\) as a function of relative velocity#

For a massive particle this has strong consequences. In the limit \(u\to c\) the factor goes towards infinity. If we consider that the kinetic energy is \(E=m\gamma(u)c^2\), the amount of work done to increase the speed increases with \(\gamma\). Therefore no massive particle can move with the speed of light (or faster) as this would require an infinite amount of energy for the acceleration.

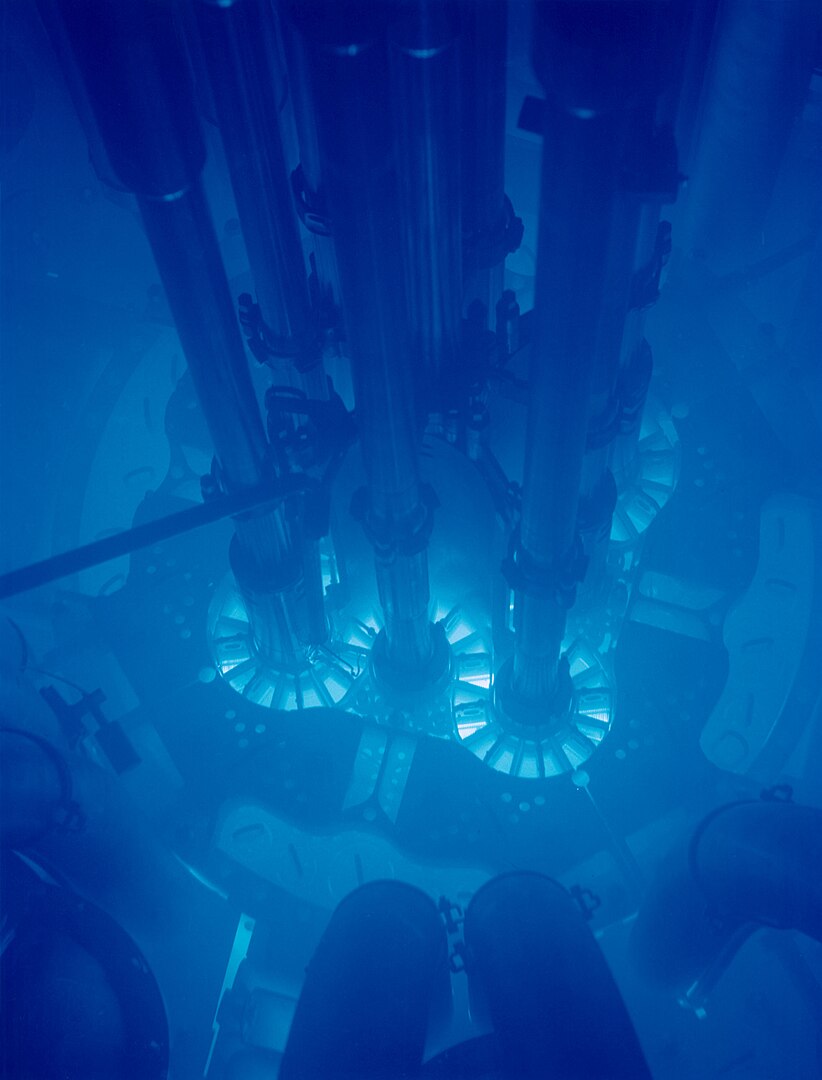

NB: \(c\) is the speed of light in vacuum. In matter the speed of light \(v\) is smaller than \(c\), characterized by the refractive index \(n\) as \(n=c/v\). This leads e.g. to refraction by Snell’s law at an interface. In matter the speed of massive particles can be larger than the speed of light there. This happens e.g. in a nuclear reactor when electrons move faster than the speed of light in water (\(0.75c\)). As water is a dielectric, the light waves generated from the response to the moving charge lag behind and a phenomena similar to a sonic boom is created. This phenomena is termed Cherenkov radiation. If you have the opportunity to see it in a nuclear reactor, we highly recommend to take it. The color is a very intense deep blue.

Fig. 20.3 Cherenkov radiation glowing in the core of the Advanced Test Reactor at Idaho National Laboratory (Wikipedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)#

20.8. Worked Examples#

Example 1

Momentum of an accelerated electron: compute the momentum and speed of an electron after acceleration in a potential of \(V=300\) kV.

From \(E^2=(mc^2)^2+(pc)^2\) we have \(p=\frac{1}{c}\sqrt{E^2-(mc^2)^2}\) and using \(E=mc^2+E_{kin}\) we have

With \(E_{kin}=300\) keV and \(m_e=511\) keV. The speed can be computed from rearranging \(E_{kin} = mc^2(\gamma -1)\) to \(\frac{v}{c} = \sqrt{1- \frac{(mc^2)^2}{(E_{kin}+mc^2)^2}}=\sqrt{1-\frac{511^2}{811^2}}=0.77\). Please observe how practical it is to use the units eV!

Example 2

Decay of a neutral kaon into three pions. \(K^0 \to \pi^- + \pi^+ + \pi^0\). Show that the three pions trajectories are in one plane.

In the rest frame of the kaon we have \(\vec{p}_K=0\) before the decay. By conservation of momentum we have after the decay \(\vec{p}_{\pi^-} + \vec{p}_{\pi^+} +\vec{p}_{\pi^0}=0\). A necessary and sufficient condition for three vectors \(\vec{p}_1,\vec{p}_2,\vec{p}_3\) to lie in one plane is that \(\vec{p}_1 \cdot (\vec{p}_2 \times \vec{p}_3)=0\) (Remember that this expression gives the volume of the parallelepiped spanned by the three vectors). From the conservation of momentum we have \(\vec{p}_1 = -\vec{p}_2 -\vec{p}_3\). Now we can compute \((-\vec{p}_2 -\vec{p}_3)\cdot (\vec{p}_2 \times \vec{p}_3)=-\vec{p}_2\cdot(\vec{p}_2 \times \vec{p}_3)-\vec{p}_3\cdot(\vec{p}_2 \times \vec{p}_3)=0\). The two terms are each zero individually as the term in the bracket is perpendicular to \(\vec{p}_2\) and \(\vec{p}_3\) respectively.

If the trajectories in the rest frame of the kaon are in one plane, then they are also in one plane in all other frames. A coordinate transformation only shifts or rotates, which transfers a plane into a plane, but does not e.g. shear or bend a plane.

20.9. Exercises#

Exercise 20.1

Observer \(S\) and \(S'\) are connected via a Lorentz Transform of the form

with \(V/c = 12/13\).

\(S'\) observes a particle of mass \(m\) traveling in the positive \(x'\)-direction with velocity \(U'/c=40/41\).

Find, using the 4-velocity, the velocity of m according to \(S\).

Exercise 20.2

Observer \(S\) and \(S'\) are connected via a Lorentz Transform of the form

with \(V/c = 12/13\).

\(S'\) observes a particle of mass \(m\) traveling in the positive \(y'\)-direction with velocity \(U'/c=40/41\).

Find, using the 4-velocity, the velocity of m according to \(S\).

Exercise 20.3

According to \(S'\) a photon is emitted at \(t'=0\) from position \(L_0 = 1 ls\) towards the origin \(\mathcal{O}'\). It has a frequency \(f_0\). \(S'\) is traveling at \(V/C = 3/5\) in the positive \(x\)-direction with respect to \(S\). They have synchronized their clocks when their origins coincide. Determine the time of detection by \(S'\) and by \(S\). Find the frequency that \(S\) measures.

Exercise 20.4

In this exercise, the photon is emitted to \(S'\) over the \(y'\)-axis. It has again a frequency \(f_0\). \(S'\) is traveling at \(V/C = 3/5\) in the positive \(x\)-direction with respect to \(S\). They have synchronized their clocks when their origins coincide.

Find the frequency that \(S\) measures and the angle the traveling photon makes with the \(x\)-axis.

20.9.1. Answers#

Solution to Exercise 20.1

According to \(S'\)

LT naar \(S\) using \(\gamma (V) = \frac{13}{5}\):

We find \(u_x\) by taking the ratio \(\frac{U_1}{U_0} = \frac{\gamma(U)u}{\gamma(U)c}\):

Solution to Exercise 20.2

According to \(S'\)

LT naar \(S\) using \(\gamma (V) = \frac{13}{5}\):

We find \(u_x\) by taking the ratio \(\frac{U_1}{U_0} = \frac{\gamma(U)u_x}{\gamma(U)c}\):

Similarly:

The magnitude of the volocity accoring to $S4 is

Solution to Exercise 20.3

According to \(S'\) the photon is send at \(E_1: (ct'_1, x'_1 ) = (0, 1) ls\). Thus, it is received at \(E_2: (ct'_2, x'_2 ) = (1,0)\). Hence, for \(S\) event \(E_1\) has coordinates:

and thus, \(S\) receives this photon at \((ct_3, x_3) = ( 2, 0)ls\).

For \(S'\) the 4-Momentum of the photon is: \(\left ( \frac{hf_0}{c}, -\frac{hf_0}{c}\right )\). If we transform this to the frame of \(S\), we get:

Solution to Exercise 20.4

In this case for \(S'\) the 4-momentum of the photon is:

If we translate this to the world of \(S\), we need to realize that momentum is a vector and that the spatial parts, i.e. \(P^1, P^2, P^3\) form a vector. In this case, there is no \(z\)-component and we can write the \(x\) and \(y\)-components as the length of the vector times a \(\cos\) and a \(\sin\), respectively:

Thus, from the time-like component we conclude: \(f = \frac{5}{4}f_0\). This should be in agreement with the spatial components. Let’s check:

Indeed, the two spatial components are in agreemnt with the time-like one.

Finally, we have that according to \(S\), the photon travels at an angle \(\tan \alpha = \pm \frac{4}{3} \rightarrow \alpha = \pm 53.13^\circ \) with the \(x\)-axis.