17. Length contraction & Time dilatation#

17.1. First Implications#

As we have seen, we need to use the Lorentz Transformation instead of the Galilei one when two observers, \(S\) and \(S'\), want to exchange information. What does change if we do so? Let’s first do some examples and see some of the consequences and the ‘strange’ conclusions we need to draw.

Note: we will frequently use high velocities and large distances. It is convenient not to write these in units like \(m\) and \(m/s\). The numbers in front of them become so large that keeping an overview becomes cumbersome. Therefore, we will change to a different unit for distance: the light second. That is per definition the distance a photon of light ray travels in one second (in vacuum):

For instance, it takes a photon about 8.3 minutes to travel from the sun to the earth. Thus, the distance from the sun to the earth is \(8.3 lmin = 500 ls\). That is equivalent to \(150 \cdot 10^ km\).

17.1.1. Worked Example#

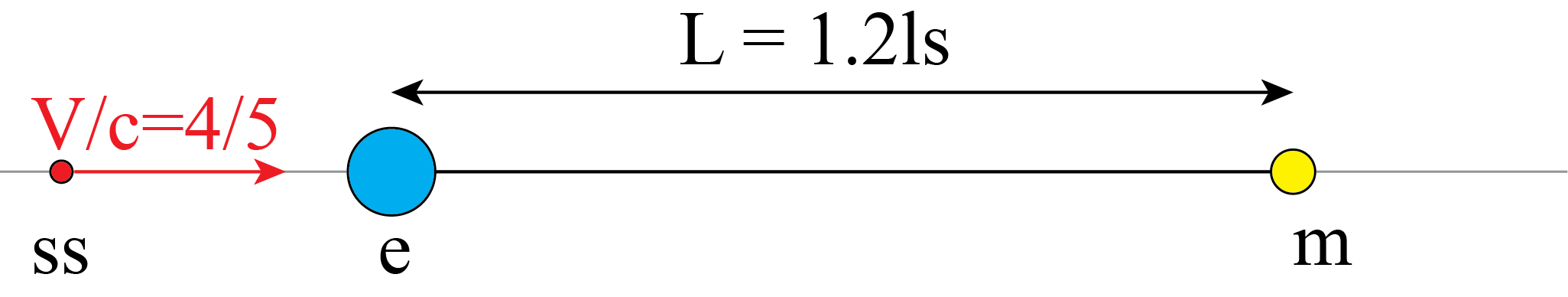

A space ship is flying at a velocity 0.8c passed earth in the direction of the moon. The moon is at a distance of 1.2 ls (that is some \(3.6 \cdot 10^8\)m) from the earth. The clocks on earth and in the space ship are set to zero when the space ship passes the earth.

At time \(t = 1.7 ls\) observer \(S\) of the earth observes that a big comet strikes the moon surface.

When does \(S'\), who is on the space ship, see this happening?

Solution

First we make a sketch.

Next, we need to carefully clarify what we mean by observe, know, see. This is very important as observations are made by someone at a certain time, while being at a certain position. Since now both time and place information gets into the transformation, being sloppy might lead to very strange and wrong conclusions.

Thus, we will from now on, specify Events. An event is a physical phenomenon happening at a certain place at a certain time. For instance, you catching a frisbee at 12:45 (i.e. \(t_f\)) on the campus (at location \(x_f\), \(y_f\), \(z_f\)). This will be denoted as:

That is, four coordinates are specified (in \(m\) or \(ls\) or …). Note: this is information as used by \(S\): the coordinates do not carry a prime.

So, back to our example: we have our first event:

What does this mean? Observer \(S\), who is sitting in \(\mathcal{O} = (0,0,0)\) literally sees that the comet hits the moon. He does so at \(t_1 = 1.7s\), i.e. \(ct_1 = 1.7 ls\). In terms of physics: a photon hits his eye at \(ct_1\). The observer has zero-size, that is everything he observes is done at (0,0,0).

Now, we need to realize, that the actual impact of the comet took place earlier. By how much? Well, a photon that was generated at this moment of impact due to the impact will have to travel a distance of 1.2ls to \(S\). That requires 1.2s, as photons travel with the speed of light.

Thus, \(S\) concludes that the actual impact -which is event \(E_2\)- took place at \(ct_2 = 0.5ls\) and he writes down:

Again notice that we have updated this event not only by using the actual time, but also the actual place, i.e. at \(x_2\).

\(S\) passes this information on to \(S'\). She has to translate it to her own coordinates and uses for that the Lorentz transform.

First, she needs to calculate the \(\gamma\)-factor:

Now she computes her coordinates for the same event:

We will not further deal with the \(y\) and \(z\) coordinates as they are trivial.

But, we might get our first surprise here. According to \(S\) the impact of the comet happens at \(t = 0.5s\) That is at a positive time. Then, Space Ship has passes the earth and is on its way to the moon. Actually, at \(t=0.5s\) the location of Space Ship is, according to \(S\): \(x_{SS}(t) = V t = \frac{V}{c} ct \rightarrow x_{SS}(0.5s) = \frac{4}{5} 0.5 = 0.4 ls\). Space ship is already at 1/3 of the distance to the moon.

So far nothing strange.

But now we consider \(S'\). She says: the impact of the comet was at \(t' = -0.767\). This means that according to her, the impact took place when she was still approaching the earth. After all, negative times mean that Space ship is approaching the earth (and is to the left of it in our sketch), while positive times mean that Space Sip has passed the earth and is moving away - thus is at the right side of earth in our sketch.

And this is so according to both \(S\) and \(S'\). They may use different times, but they have set their clocks to zero when earth and Space ship were in ‘the same position’.

Ok, let’s be puzzled for a while: how can \(S'\) at the same time be both at the left side and at the right side of the earth? That doesn’t make any sense!!!! What is wrong with this new theory? The answer is: nothing!

It is us, mixing stuff up. Who said that it is ‘at the same time’?!? Nobody (with perhaps for a moment us as the exception). \(S\) and \(S'\) agree upon the event: a comet hits the moon. This physical phenomena is not disputed at all. It happened. They don’t agree that it took place at the same time according to their clocks.

But this is not all: according to \(S\) at the moment of the impact Space Ship was at a distance of \(1.2 - 0.4 = 0.8 ls\) from the moon. But \(S'\) just calculated that she was \(1.33 ls\) from the moon. One can not be at two different distance form the moon at the same time!

Ok, let’s push this somewhat further and see if we can get a contradiction.

We do know, from \(S\), that the event took place at \(ct_2 = 0.5 ls\). Then, definitely \(S'\) has passed earth. \(S\) has reconstructed this event from observation Event \(E_1\). \(S'\) got the information of event \(E_2\) from \(S\) and back out the coordinates of the event in her coordinate system. From these data, \(S'\) can easily predict when she will see the impact. That is obviously later then the time of the event: the photons have to travel to her. How can we compute when \(S'\) literally sees the event?

That is remarkably easy: we know that according to \(S'\) the event tokes place at \((ct'_2, x_2') = (-0.767 ls, 1.333 ls)\). At that moment and that place a photon was generated that moves in her direction. Since the velocity of each photon is always \(c\), we can easily find the time when \(S'\) sees the photon, i.e. detect it at location \(x'=0\). The photon has to travel a distance \(1.33 ls\) at a speed of \(1 c\). That will take 1.33s. The photon started traveling at time \(ct_2 = -0.767\). It’s trajectory according to \(S'\) is \(x'_p(t') = x'_p(0) - c (t' - t'_2)\).

Thus, the photon gets measure at event \(E_3\): \(x_3' = 0 \rightarrow ct'_3 = x'_2 + ct'_2 = 0.567 ls\). Thus we have our third event:

And as we by now kind of expected: indeed, then is Space Ship on the right side of the earth. What does \(S\) say about this event? He receives the coordinates of \(E3\) from \(S'\) and plugs them in the inverse LT:

Now does this make any sense? It does! If we concentrate on \(S\) only and what he observes and knows:

-

\(E_1\) - \(S\) observes -comet hits moon: \((ct_1,x_1) = (1.2, 0) ls\)

-

\(E_2\) - the comet actually hits the moon: \((ct_2,x_2) = (0.5, 1.2) ls\)

-

\(E_3\) - \(S'\) observes that the comet hits the moon: \((ct_3,x_3) = (0.945, 756) ls\)

Obviously, if the actual impact is at positive \(t\), then \(S'\) will see it before \(S\) does as for positive time \(t\) \(S'\) is closer the moon than \(S\). And this is all reflected in the events. Moreover, if you would compute the events as \(S\) will model things, you will find event \(E_3\) just based on event \(E_2\) and the motion of Space Ship according to \(S\) (and when it will encounter a photon that was generated at the actual impact of the comet on the moon). Do the calculation yourself and see that nothing strange happens.

We can draw the position of earth, moon and space ship in space-time plot. It is customary to use as horizontal axis the \(x\) or \(x'\) coordinate and as the vertical one \(ct\) or \(ct'\).

\(S\) will see the earth and moon standing still and thus draw a vertical line in the space-time diagram for each of them: they do not change position, but their time is changing, i.e. the clock ticks. \(S\) would draw for Space Ship a straight line moving from left bottom to upper right as the space ship moves in the positive direction.

Similarly, \(S'\) will draw a vertical line for space ship itself, as in the frame of reference of \(S'\) the space ship, obviously, does not move. The earth and moon move to the left, thus their trajectories are straight line from the bottom right to the upper left in the \((x', ct')\)-diagram.

At some moment in time-space the comet impacts the moon and a photon is moving in the negative \(x\)-direction towards the earth. Somewhat later, this photon is received by earth. In the \((x,ct)\)-diagram this is a straight line from lower right to upper left.

In the animation below the whole scenery is shown from the perspective of \(S\) on the left side and from \(S'\) on the right side. The diagrams are made such, that the event “Space Ship passes earth” is simultaneous in both diagrams, i.e. it happens for both observers at their time equal to 0. All other events happen at different times according to the clocks of the observers.

Fig. 17.1 Relativistic simultaneity and motion in two frames#

In the animation given above, we can see the following:

- the three squares represent the position of earth, moon and Space Ship according to

\(S\) at \(ct=-1\)ls. In the diagram for \(S\), these three squares are, of course, on a horizontal line as they are at the same time according to \(S\).

However, \(S'\) sees that differently: they are absolutely not at the same time!!!

- Earth, moon and Space Ship do travel in the space-time diagrams. Their trajectories are shown by dashed lines. Their space-time location is represented by the (moving) dots. The diagrams are made such, that indeed both observers pass each other at

\(ct=ct'=0\) and \(x=x'=0\). The dots represent, where according to \(S\) (left diagram) and \(S'\) (right diagram) earth, moon and Space Ship are at a certain time on the clock of that observer. Note that both position and time have really different values if you compare the diagrams of \(S\) and \(S'\).

- In both diagrams, at some point in time the comet impacts the moon and a photon starts traveling in the negative

\(x\) and \(x'\)-direction. The photon is shown by the blue dot. Again nothing happens at the same time. But the order of events is the same: first the photon is emitted and only after that it is observed. That should of course hold!

- Notice that the photon is emitted at

\(ct=0.5\)ls according to \(S\) and observed at \(ct=1,7\)ls. So for \(S\), the photon traveled for 1.2s (and covered a distance of 1.2ls: of course, photons travel with velocity c). However, for \(S'\) this is quite different: the photon is emitted at \(ct'=-23/30\), that is much earlier than \(S\) reports. Moreover, it is only registered by \(S\) on \(ct'=85/30\)ls. It traveled for 3.6 seconds on the clock of \(S'\)!!

Puzzled by this all? Confused? Hard to believe?

Welcome to the ‘Magical World of Relativity’. And don’t worry: you will get used to it. Moreover, we will develop a mathematical framework that helps us and prevents our failing intuition to take the wrong path.

Conclusions:

- we need to be careful with interpreting distances and times, things are not what they seem at first glance.

- within the framework of one observer nothing funny happens.

- we better work with well defined events: they represent physical phenomena happening. Both observers will agree upon these and on the logic, e.g. first the impact than the observation of a photon - not the other way around!

17.2. Time & Space#

Here we have a look at the consequences of axioms 1 & 2. We know how two observers \(S\) and \(S'\) (moving away with \(V\)) transform their respective coordinates into each other, via the Lorentz transformation.

Lorentz Transformation

We will look at the consequences for time and space coordinates.

17.2.1. Relativity of simultaneity#

From the Lorentz transformation it is clear that time is not universal anymore (\(ct'\neq ct\) in general). This is a large step from Newton and Galileo. Now the time coordinate is mixed somehow with the space coordinates depending on the speed \(V\).

Let us consider 2 events in the reference frame of \(S\);

event A with coordinates \((ct_1, x_1)\)

and event B with \((t_2, x_2)\)

If the two events in \(S\) are simultaneous, i.e. \(t_1=t_2 \rightarrow ct_1-ct_2=0\), then in \(S'\) they are in general not! Simultaneity is relative!

Even though the first term \((ct_1-ct_2)=0\) the second term \((x_1-x_2)\) is never zero unless \(x_1=x_2\), and \(ct'_1-ct'_2 \neq 0\) in general.

In words: The events A and B that are simultaneous for \(S\), are never simultaneous for \(S'\), unless the events are happening at the same place.

Relativität der Gleichzeitigkeit as Einstein called it, is the first very counterintuitive consequence by simple application of the Lorentz transformation. Our brains are not trained and build to cope with this aspect of nature. There is just no evolutionary advantage to it as all relevant speeds are much smaller than the speed of light.

17.2.2. Time dilation#

We investigate how time intervals between a stationary and a moving observers are transformed. We can expect that these time intervals are not the same. Let us consider two identical clocks: one stationary with \(S\), the other traveling with \(S'\).

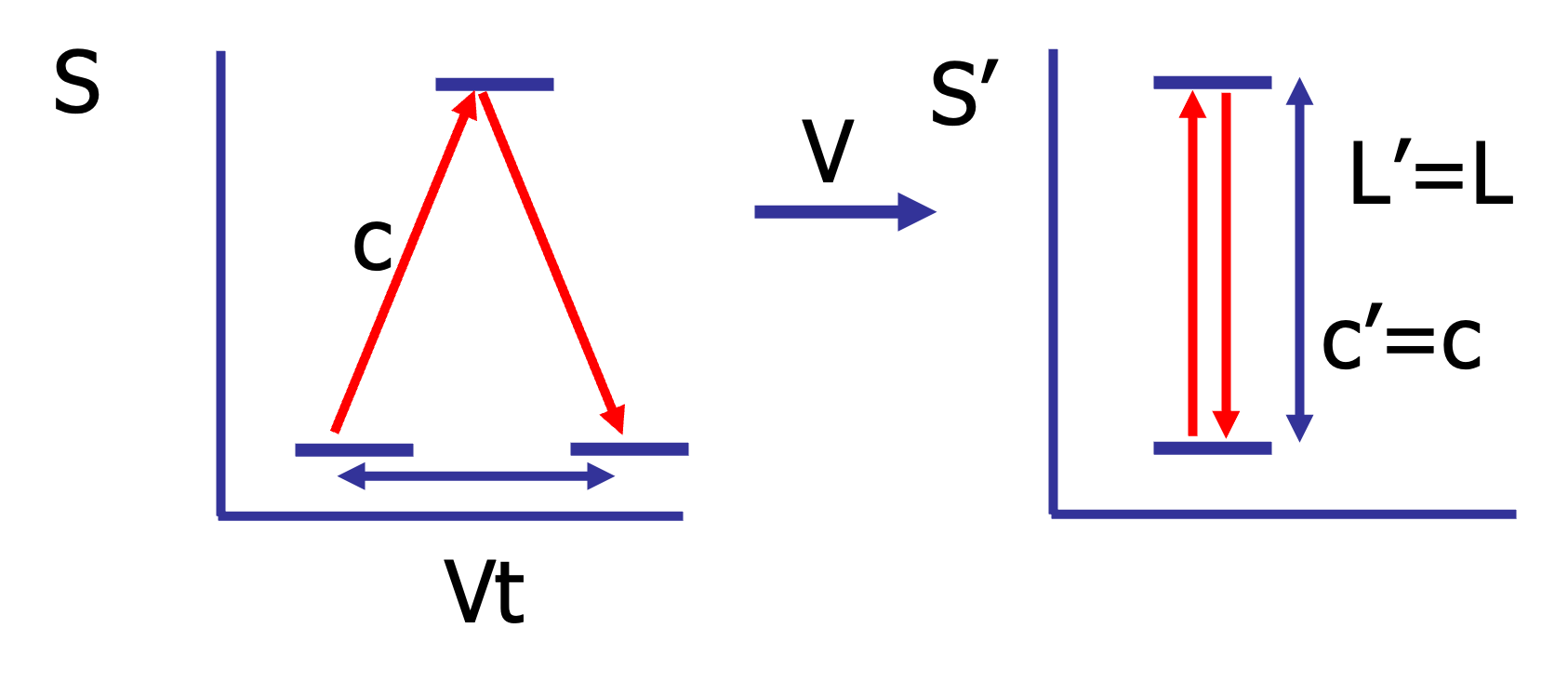

Fig. 17.2 Clock stationary according to \(S'\) but moving for \(S\).#

Consider the sketch above: it shows the clock stationary in \(S'\).

We see how time intervals are counted for a moving observer and for an observer in the rest frame. A light ray is traveling between 2 mirrors. This up and down traveling of the light is a counter for the time. If you have never thought how time is measured, think a bit how a clock actually does that. Today, the second is defined as a (very large) number of tiny energy transitions (vibrations) of the Caesium-133 atom (see e.g. Atomic Clock).

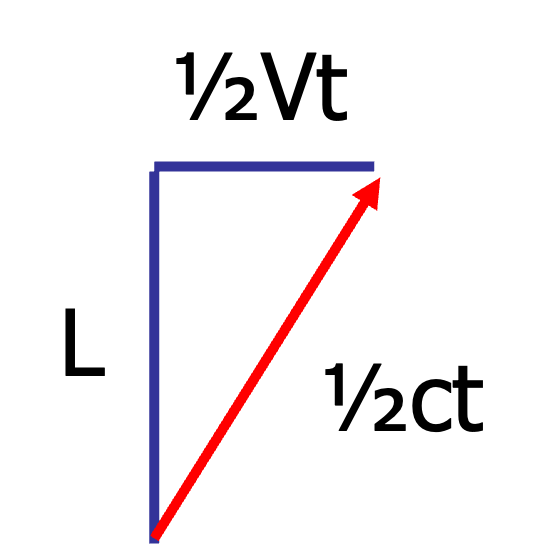

Consider the time light travels according to the observer \(S\) who sees the clock moving with velocity \(V\). The clock counts one unit of time, \(t\) if the light has gone from the bottom mirror to the top one and back to the bottom mirror. Thus from bottom to top takes \(t/2\). This means that the length of the light path from bottom mirror to top mirror is equal to \(ct/2\) as light travels with velocity \(c\). In that same period of time, the top mirror has moved a distance \(Vt/2\), as the clock and thus the mirrors move with velocity \(V\) with respect to observer \(S\). Now, we can relate the length of the light path from the bottom to the top mirror to the size of the clock, \(L\) and the displacement of the mirror, \(Vt/2\):

\(L^2+\frac{V^2}{4}t^2=\frac{c^2}{4}t^2\) where we used Pythagoras, see figure below.

Fig. 17.3 Light path in a moving clock.#

We can solve this for the time \(t\) that the stationary observer \(S\) puts to the moving clock

We see directly that the time the stationary observer \(S\) records is larger than the moving observer \(S'\) itself which is just \(2L/c\) (the time in her rest frame)! The time interval gets longer/dilated by the \(\gamma\)-factor.

with \(\gamma=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{V^2}{c^2}}} >1\) and \(T_0\) the proper time or eigen time in the rest frame.

Note: a time interval is also the counting of your heart. That means the moving observer ages more slowly compared to the observer at rest. See the examples for some experimental evidence of the time dilation.

Conclusion: moving clocks run slower, time gets stretched

17.2.3. Length contraction#

The length of moving objects becomes smaller/contracted for the observer at rest. To explain this effect, we consider a moving rod with velocity \(V\) and with length \(L_0\) in the rest frame.

Now that we have seen that time intervals are no longer universal, we need to think about:

“what is it, measuring the length of an object?”

Normally, we measure the length of an object by seeing how many times a measuring stick fits in the object. We obviously do this in the frame of reference in which the object doesn’t move. There we don’t need to worry about the moment we start at the left side of the object and arrive with our measuring stick on the right side. But if we would do so in a frame of reference in which the object is moving, that wouldn’t work of course. By the time we would reach the right side of the object, it would no longer be at its starting position when we began our measurement and the number of times our ruler fits in the object is now influence by the motion of the right side of the object.

To measure the length of a moving object, we thus need a different strategy. What we could do, is having a very long ruler fixed in our system. The object is moving passed it. If we have two observers, one concentrating on the left side of the object and the other on the right side, we could ask them to measure the position of the left and right side of the object along the ruler at the same time. Then the difference of the left and right side on the ruler will give us the length of the object.

Thus: the length is measured from the difference of two events in space-time of the front and the back of the rod. We will call the events \(E_L: (ct_1, x_1)\) and \(E_R: (ct_2, x_2)\). As we measure size, we require: \(t_1 = t_2\), that is the measurements are done simultaneously in \(S\). According to \(S\), the length of the rod is \(L = x_2 - x_1\), nothing special here.

Next we transform the events \(E_L\) and \(E_R\) to \(S'\):

For \(S'\) the difference between \(x'_2\) and \(x'_1\) is of course the length of the rod. It doesn’t matter for \(S'\) whether or not the coordinates the left and right side of the rod are measured at the same time. The rod is not moving in the frame of \(S'\). Thus \(S'\) gets as length of the rod:

with \(L_0\) the proper length of the rod, i.e. the length according to an observer moving with the rod.

Now we invoke the Lorentz transformation for the two events \(E_L\) and \(E_R\) to find the relation between the coordinates used by the two observers:

As we measure \(x_1,x_2\) at the same time in \(S\), we have \(ct_2=ct_1\).

The length of the moving object observed by the stationary observer is not the same as the length in the rest frame. The length observed by the stationary observer \(S\) gets smaller/contracted by \(\gamma>1\) compared to the length in the rest frame of \(S'\): \(L<L_0\).

Conclusion: moving rods are shorter, space shrinks

17.2.4. Paradox: twins and barns#

17.2.4.1. Barn & Ladder#

There are many variants of the following paradox. The word paradox already implies that there is only an apparent contradiction, not a real one. Here we will formulate the paradox with a ladder & barn and resolve it, but you can also think about it as a train & tunnel, or tank & trench etc. The resolution is always the same.

As an example we consider a ladder of rest length \(L_l=26\) m and a barn of rest length \(L_b = 10\) m. Obviously, the ladder does not fit in the barn, isn’t it?

Now consider that the ladder is moving with velocity \(V=\frac{12}{13}c\ (\gamma =\frac{13}{5})\) towards the barn.

For an observer in the barn, the length of the ladder is contracted to \(L_l/\gamma = 26\cdot\frac{5}{13}=10\) m exactly fitting in the barn which in his rest frame is 10 m.

For an observer moving with the ladder, the barn gets contracted to \(L_b/\gamma= 10\cdot\frac{5}{13}=50/13 \sim 4\) m, being much too small to fit in the ladder. The ladder in his rest frame is 26 m.

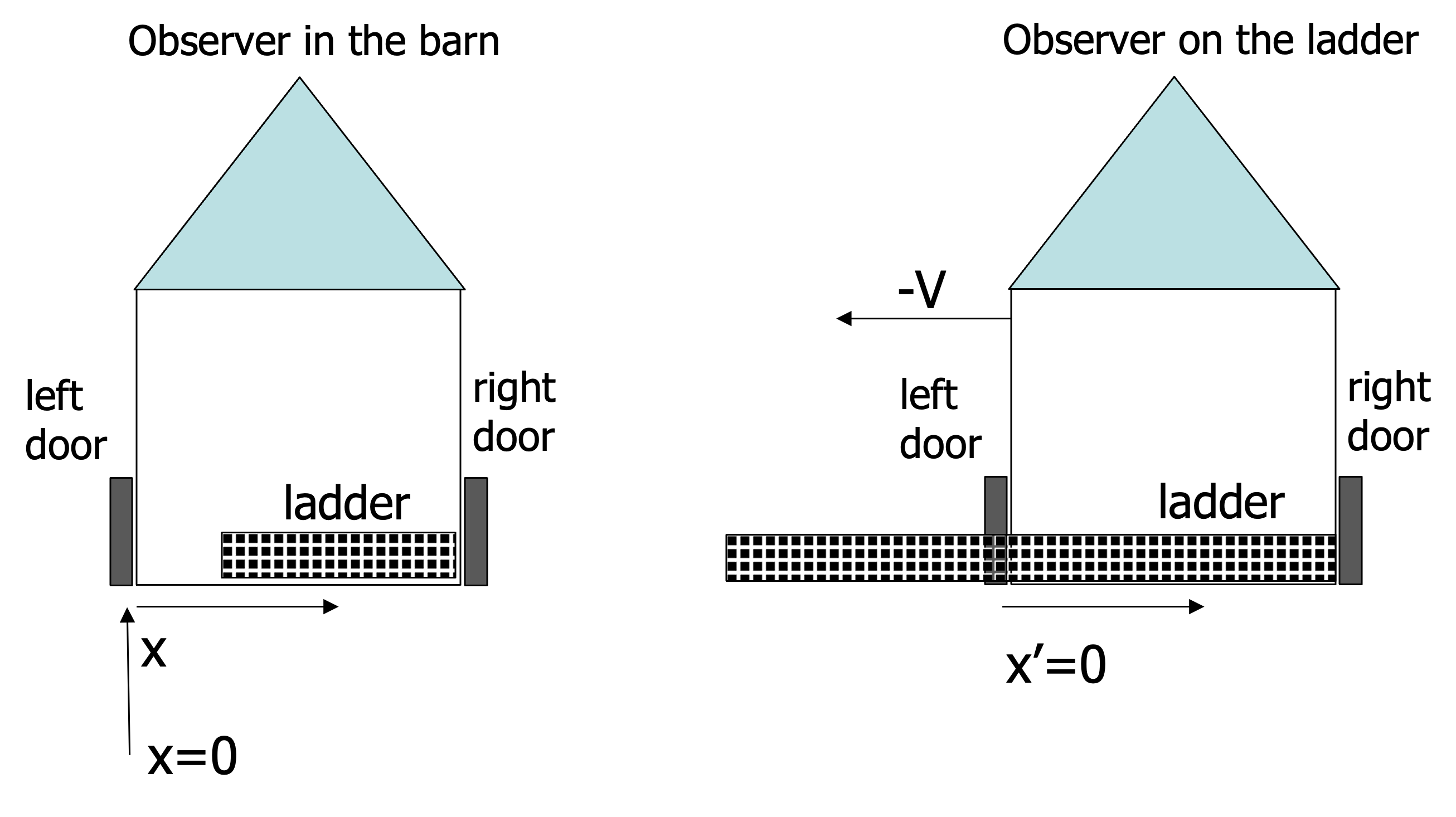

Fig. 17.4 Ladder & Barn: perspective from two observers.#

We have applied the Lorentz transformation or length contraction (time dilation) and the concept of relativity correctly, but something seems wrong! The physical outcome must be the same for both observers, but one observer claims the ladder perfectly fits into the barn, the other say it does not! That is: the observer in the barn can close the left and right door when the ladder is just inside the barn. Of course, the doors need to be open again very quickly as the ladder is moving with high velocity to the right. But that doesn’t take away the fact that the doors were closed and the ladder was inside the barn. How does the other observer cope with this?

You can have the same paradox not with length contraction, but time dilation, then it is called the twin paradox. We discuss the twin paradox later in the framework of Minkowski-diagrams.

Solution

The key to the resolution of the paradox is always the relativity of simultaneity. In this instance of the paradox with the barn and ladder. Both observers are right but do not agree when the measurements are done.

Here we analyze the situation in detail using the Lorentz transformation. Later you can analyze it again qualitatively using a [Minkowski-diagram](./ChX9_FourVectors.md#the-ladder–barn-revisited which is quite insightful.

Our above “analysis” was a bit short: using length contraction. It is also a bit ‘dangerous’ as length contraction assumes simultaneous events in one frame.

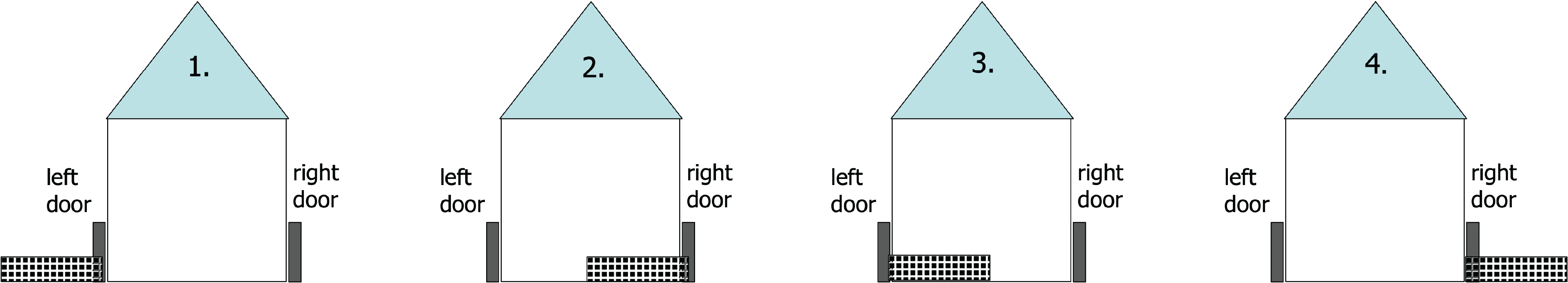

We will consider how both observers would actually measure things in their respective frames of reference and in which order things happen. It turns out that both points of view are correct, but with a twist. We define 4 events to analyze the situation.

Event 1: right end ladder at left door barn

Event 2: right end ladder at right door barn

Event 3: left end ladder at left door barn

Event 4: left end ladder at right door barn (not really needed)

The four events are sketched in the figure below

Fig. 17.5 Four events of the ladder & barn paradox#

Note: the size of the ladder in the sketch above is of course open for debate between the two observers :-).

Observer Barn (\(B\)) will conclude that the ladder fits inside the barn and actually is inside the barn if Event 3 is earlier then Event 2, according to observer \(B\)’s clock. If, however, Event 3 is later than Event 2, the ladder does not fit. Similarly, observer Ladder (\(L\)) will draw the same conclusions, but based on the clock of observer \(L\).

Let’s analyze these events. We will denote the coordinates of observer \(B\) as \((ct,x)\) and those of observer \(L\) as \((ct', x')\). Both observers agree that they will call the position of the left door the origin, that is \(x_{LD} = x'_{LD} = 0\). Moreover, they agree that at the moment the right end of the ladder is at the left door, they will set their clocks to 0. Remember: according to observer \(B\), the length of the ladder is \(L_{0L}/ \gamma\) = 10 m, which happens to be the size of the barn according to \(B\). We anticipate that \(B\) will conclude that the ladder fits.

Next, we need to give the events their space-time coordinates, e.g. in \(B\)’s frame and transform these coordinates according to the LT to \(L\)’s frame. This is done below, where we used: \(L_{0B}\) = proper length of barn, i.e. in the rest frame of the barn and \(L_{0L}\) = proper length of ladder, that is in the rest frame of the ladder. As example: E2, when is the right side of the ladder at the position of the right door? Solution: \(x_{right \; end \; ladder}(t) = \frac{V}{c} ct \) and \( x_{right \; door} = L_{0B}\) Thus, the right end of the ladde is at the position of the right door of the barn at \( ct = \frac{V}{c}L\_{0B} \)

Note: \(V/c = 12/13 \Rightarrow \gamma = 13/5\)

Event |

Barn \((ct, x)\) |

Ladder \((ct', x')\) |

|---|---|---|

1 |

\((0, 0)\) |

\((0, 0)\) |

2 |

\(\left(\dfrac{c}{V}L_{0B},\ L_{0B}\right)\) |

\(\left(\dfrac{c}{V}\dfrac{L_{0B}}{\gamma},\ 0\right)\) |

3 |

\(\left(\dfrac{c}{V}L_{0B},\ 0\right)\) |

\(\left(\gamma\dfrac{c}{V}\dfrac{L_{0B}}{\gamma},\ -L_{0L}\right)\) |

As we see, according to \(B\), the left and right end of the ladder are exactly at the same moment at the left and right door of the barn, respectively (time coordinate of events 2 & 3 \(ct_2=ct_3=\frac{c}{V}L_{0B}\)). Consequently, observer \(B\) measures that the ladder (just) fits into the barn as anticipated by us. So \(B\) can close both doors and have the ladder inside the barn.

However, if we look at events 2 & 3 according to \(L\), we see that \(L\) measures that the right end of the ladder is much earlier at the right door (event 2 \(ct'_2=\frac{c}{V}\frac{L_{0B}}{\gamma}\)), than the left end is at the left door (event 3 \(ct'_3>ct'_2\)). So, according to \(L\), when the ladder hits the right end of the barn, the left part of the ladder is still left from the left door, thus outside the barn. The ladder does not fit. Of course, \(L\) sees that \(B\) closes the doors of the barn, but contrary to what \(B\) says: ‘I closed the doors simultaneously and the ladder was in my barn”, \(L\) will respond: “that may be true for you, but I clearly observed that you first shut the right door, while the left was still open. Then you quickly opened the right door to let the ladder pass and only after a while, when the left side of the ladder was just inside your bar, you closed the left door. The ladder was never inside the barn with both doors closed!”

The paradox is, that both observers are right. Again we see demonstrated that simultaneous for one does not necessarily mean simultaneous for another. Very counter intuitive and yet: very true.

As you see both observers do not agree where the ladder is when the left door is closed. Where for the barn observer both doors closes at the same time, this does not happen for the ladder observer.

17.2.4.2. Worked Example#

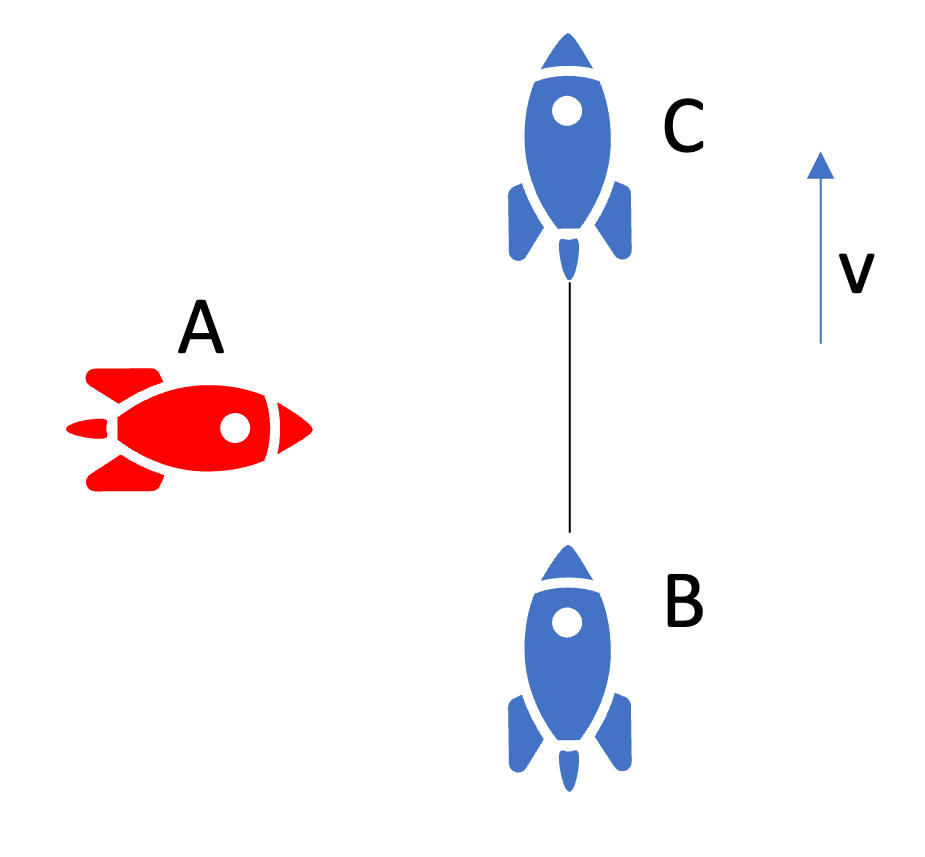

This problem became known through John Bell.

“Why you absolutely need to know John Bell”

John Bell became famous by the inequalities that have his name attached. Bell’s theorem from 1964 started to end (post mortem) the twist between Einstein and Bohr about quantum mechanics in favor for Bohr. In 1935 Einstein, Polodsky and Rosen came up with a paradox, named EPR paradox after their names, that seemed to show that quantum mechanics cannot be “complete” (.i.e the real thing describing reality). Bell’s inequalities allowed to experimentally test who was right, and Einstein was fundamentally wrong. In 2022 the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Clauser, Aspect and Zeilinger for their efforts to experimentally show that the Bell’s inequalities are violated (and Bohr was right). In Delft Roland Hanson performed a loophole-free Bell test in 2015 which was big news. Why is this so important? It touches the heart of what is reality, is it deterministic and/or local now that quantum mechanics turned out to be the real thing? How we see reality now boils down to how we interpret quantum mechanics - and that is difficult to comprehend. The Copenhagen interpretation is so frustrating as the wave function collapses at measurement, however, the many-world interpretation that avoids the collapse is also not very appealing as it needs an infinite number of universes. This remains one of the important open ends in physics. In the next thought experiment we have two space ships \(B\) and \(C\) initially at rest and space ship \(A\) as observer. \(B\) and \(C\) are connected by a tight but fragile string between them. \(A\) simultaneously signals \(B\) and \(C\) to accelerate equally, and \(B\) and \(C\) will have the same velocity at every time from the start.

Fig. 17.6 Bell’s paradox: accelerating space ships and a thin wire.#

Question: Will the string between \(B\) and \(C\) break eventually?

Answer

Yes.

Explanation:

One might think that the whole assembly of the two ships \(B\) and \(C\) and string undergo length contraction together, thus the string would not break, but that is incorrect.

As seen from \(A\)’s rest frame, \(B\) and \(C\) will have at every moment the same velocity, and so remain displaced one from the other by a fixed distance. The tying will not be long enough anymore due to length contraction and therefore break.

The distance between \(B\) and \(C\) in the rest frame of \(B\) or \(C\) increases however as the acceleration from neither of them is simultaneous (if you work this out the relativity of simultaneity is the issue)! The thread breaks also in their frame.

If you got this wrong, do not worry, most people do (that is trained physicists).

If you think about this example for a bit, it becomes clear that relativistic acceleration is very troublesome for the structural integrity of extended objects! Another problem for our hopes of space travel to far away places.

17.3. Examples#

Example 17.1: Muon production in the upper atmosphere

Muons are elementary particles of the lepton family, the heavier brother of the electron. Muons decay via \(\mu^- \to e^- + \bar{\nu}_e + \nu_\mu\) (or \(\mu^+ \to e^+ + \nu_e + \bar{\nu}_\mu\). NB: You need the neutrinos to conserve lepton number) with a mean lifetime of \(\tau=2.2\ \mu\)s. Muons are generated in the upper atmosphere (at ~20 km height), when a high energetic cosmic ray hits a nuclei, as decay products. The speed of the muons is about \(v=0.99 c\). If you compute velocity times lifetime \(\tau v < 1\) km, then we conclude that nearly no muons should be detectable on the ground (assuming no other process interferes in the muons path). But we do! How is this possible?

Solution

You can solve this by considering the time dilation for an earth observer, as the lifetime is with respect to the rest frame! The lifetime for an earth observer is therefore stretched to \(\gamma \tau\sim 16\ \mu\)s. Therefore, muons only need to travel about 4 lifetimes, and a decent fraction (\(1/16\)) can still be measured on the earth surface. You can also reason via length contraction of the path the muons travel 20 km\(/\gamma\).

Example 17.2: Special relativistic correction to GPS timing

GPS uses satellites orbiting the earth at a lower altitude to determine the position. If you receive the signals from 4 or more satellites, you can compute your position by triangulation, e.g. measurement of time difference of the received signals. To this end you need a very precise timing of the signals. The satellites velocity is “slow” with \(v=4 \cdot 10^3\) m/s, and thus \(\gamma \sim 10^{-5}\ll 1\). But the error in time measurement accumulates and due to time dilation even this small \(\gamma\)-factor will increase within 1 hour to a time error of \(10^{-7}\) s or a position error of about 100 m. This would not be useful for navigation in a city and would required a recalibration of the system every few minutes. Later we see that a general relativistic effect is even more prominent!

Example 17.3: Relativistic correction to wavelength of electrons in a TEM

In a standard Transmission Electron Microscope the electrons are accelerated via electric potential differences of up to 300 kV. Assuming that particles have a wavelength via the idea of de Broglie \(E=mc^2=pc=h\frac{c}{\lambda} \Rightarrow \lambda = \frac{h}{p}\) we can use electrons as waves to image and magnify as with a normal light microscope. The smallest detail you can image with waves imaging in the far-field is given by the diffraction or Abbe resolution limit to \(d\sim \frac{\lambda}{2}\). For microscopy with visible light (\(\lambda\sim\) 500 nm) this limit is a hard restriction. For electrons of low speeds we can use \(\lambda = \frac{h}{mv}\), but for 300 kV acceleration the speed would, according to Newtonian Mechanics, be already larger than \(c\)! Later in the course you learn how to compute the relativistic momentum, filling in the numbers and the rest mass of the electron of 511 keV we obtain \(\lambda \sim 2\) pm. About 10% smaller than from classical considerations. The diffraction limit to resolution is not an issue practically for the electrons as the distances between atoms in a solid are typically \(>10\) pm.

17.4. Exercises#

Exercise 17.1

During their quest to find planets at other stars than our sun, ESA researcher discover a planet that shows striking similarities with earth. This planet orbits a star 40 lightyears from us. They start planning an expedition with astronauts. ESA requires that the astronauts upon arrival at the planet have aged no more than 30 years.

In this exercise, we ignore possible effects of acceleration. A lightyear is the distance traveled by a photon in one year.

What is the required velocity of the space ship (with respect to the reference frame of the earth) to ensure a journey of 30 years (ignore the time spent on the other planet)?

What is according to the astronauts the distance they have to travel? Does that agree with the journey time of 30 years?

To inform Mission Control on earth the astronauts send yearly (according to their clock) a report to earth. Of course, the report is coded in the form of a light pulse. What is the period between receiving two consecutive reports according to Mission Control?

Exercise 17.2

An observer \(S'\) is traveling in a fast train. According to \(S'\), the train has a length \(2L'\). The train is speeding with \(V\) over a track along the \(x\)-axis. At \(t'=0\) \(S'\) passes the origin of the frame of reference of \(S\), who is stationary with respect to the track. At the moment of passing, \(S\) sets her clock to \(t=0\).

\(S'\) is in the middle of the train. He send at \(t'=0\) two light pulses out. One in the direction of the front of the train, where this pulse reflects on a mirror and is traveling back to \(S'\). The other pulse is send to the back of the train and reflects there back to \(S'\). \(S'\) claims that both pulses are received back at the same time.

Define the events that define this problem and give the coordinates as \(S'\) would do.

Translate the events to the frame of \(S\).

Does \(S\) also see the two pulses reach \('\) at the same time?

Draw a \((ct,x)\) diagram in which the trajectories of \(S'\), front and back mirror as well as the two pulses are shown. Note: the \(ct\)-axis is the vertical axis in such a graph. Can you graphically understand whether or not the two pulses arrive at \(S'\) at the same time according to \(S\).

Exercise 17.3

Observer \(S'\) is traveling with velocity V with respect to observer \(S\). Both observers have aligned their \(x\), \(x'\) axis and set their clocks to zero when their origins coincide.

According to \(S'\), an object is approaching \(S'\) at a velocity -V. At \(ct'=0\), the object is a distance \(L'\) from \(S'\). At some moment in time it will collide with \(S'\).

The initial time and position of the object at \(ct'=0\) is marked as Event 1 by \(S'\). Provide the coordinates of E1 according to \(S'\) and according to \(S\).

Determine the event “object collides with \(S'\)” (event E2) according to \(S'\) and according to \(S\).

Can you understand the values of \(x_1\) and \(x_2\)?

Exercise 17.4

Observer \(S'\) is traveling with velocity V/c=4/5 with respect to observer \(S\). Both observers have aligned their \(x\), \(x'\) axis and set their clocks to zero when their origins coincide.

According to \(S\), an object is moving at a velocity -V/c = -4/5. At \(ct=0\), the object is in the origin of \(S\). At some moment in time, \(ct\), it is located somewhere on the negative \(x\)-axis.

Do the exercise twice: first for observers in the world of Einstein and Lorentz, second time for the world of Newton and Galilei.

Define two events: one (E1) where the object is at \(ct=0\) and the other (E2) where it is at \(ct\). Transform both objects to \(S'\).

For an object moving at constant velocity, the velocity can be found from two locations at two separate moments in time. Find the velocity of the object according to \(S'\) and show that its magnitude is smaller than the speed of light in the world of Lorentz and Einstein. To people living in the world of Newton and Galilei, this is a surprising result. They would have found a velocity magnitude larger than c.

17.5. Answers#

Solution to Exercise 17.1

Denote Mission control by \(S\) and the space ship by \(S'\). According to S, the distance to the planet is \(L=40 ly\). Thus the traveling time will be \(\delta t_e = \frac{L}{V}\), with \(V\) the velocity of the space ship according to \(S\). \(S'\) time dilation \(\rightarrow \delta t_e = \gamma \delta t_0\)

Requirement: \(\delta t_0 = 30 ly \rightarrow \frac{L}{V} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{V^2}{c^2}}} \delta t_0 \Rightarrow \frac{V}{c} = \frac{4}{5} \)Length contraction: \(L' = \frac{L}{\gamma} \rightarrow L' = \frac{40}{5/3} = 24 ly\)

According to the astronauts, the planet is approaching them with a velocity \(-V \Rightarrow \frac{V}{c} = -\frac{4}{5}\).

So they have to wait \(\delta t'_w = \frac{L'}{\frac{4}{5}c} = 30 y\)in S’ a light pulse every year. Define event = n\(^{th}\) pulse \((ct'_n, x') = (n, 0)\). The (n+1) pulse \((ct'_{n+1}, x'_{n+1}) = ( n+1, 0)\) Transform to \(S\) via inverse LT

The n\(^{th}\) pulse arrives at earth after traveling the distance \(x_n\) with the speed of light. Hence, the moment of receiving is:

Similarly for the (n+1)\(^{th}\):

So, we conclude that the time between receiving two consecutive pulses by Mission Control is:

Is that possible?

The astronauts send 30 reports while on their way to the planet as their journey to the planet takes 30 years. According to \(S\) this journey takes \(\frac{L}{V} = 50 year\). The last pulse is send 50 years after \(S'\) has left earth. This pulse need to travel 40ly and that takes 40 years. Thus it is received after 90 years. In those 90 years, 30 pulses have been received, hence Mission Control receives a pulse every 90/30 = 3 years.

This is a great example, that you need to be careful with quick answers based on time dilation. That would give \(\gamma \cdot 1 year = \frac{5}{3} year\) in between two pulses. But than we have forgotten that these pulses are not send from the same location.

Solution to Exercise 17.2

Events:

E0 - pulses send: \((ct'_0, x'\_0) = (0,0) \)

E1R - forward traveling pulse hits front mirror: \((ct'_{1R}, x'_{1R}) = (L',L') \)

E1L - backward traveling pulse hits back mirror: \((ct'_{1L}, x'\_{1L}) = (L',-L') \)

E2 - pulses send: \((ct'\_2, x'\_2) = (2L',0) \)

LT the events to \(S\)

E0: \((ct_0, x_0) = (0,0) \)

E1R: \((ct_{1R}, x_{1R}) = (\gamma (L' + \frac{V}{c} L',\gamma (L' + \frac{V}{c} L') = \gamma \left ( 1 + \frac{V}{c} \right ) L'\)

E1L: \((ct_{1L}, x_{1L}) = (\gamma (L' + \frac{V}{c} -L',\gamma (-L' + \frac{V}{c} L') =\gamma \left ( 1 - \frac{V}{c} \right ) L'\)

E2: \((ct_2, x_2) = (\gamma 2L', \gamma 2\frac{V}{c}L') \)

right pulse: first part of the traveling time is longer as the right mirror moves away, but on the way back \(S'\) approaches the pulse. The left pulse does exactly the opposite: first going to a mirror that is approaching and then moving after \(S'\) that is ‘running away’.

This becomes evident in the \((ct,x)\) diagram.

Fig. 17.7 (x,ct) diagrams for S’ and S)#

Solution to Exercise 17.3

E1:

trajectory object according to \(S' \rightarrow\) linear motion with velocity \(-V\): \(x'(ct') = L' - \frac{V}{c} ct'\)

collision with \(S' \Rightarrow x'(ct'_2) = 0 \rightarrow ct'_2 = \frac{L'}{V/c}\)

Thus, E2: \((ct'_2, x'_2 ) = ( \frac{L'}{V/c}, 0)\)

according to observer \(S\):

So, according to \(S\) the object hasn’t moved! In retrospect, this is logical: \(S'\) sees \(S\) moving at velocity \(-V\) and also sees the object moving at \(-V\). Thus in \(S\) the object has zero velocity.

Note: we will come back to the transformation of velocities. That is more subtle than it know may look.

Solution to Exercise 17.4

Special Relativity with LT

E1: \((ct_1, x_1) = (0,0)\) en \((ct_2, x_2) = (ct, -\frac{V}{c}ct)\)

LT naar \(S'\) with \(\frac{V}{c} = \frac{4}{5}\) and \(\gamma = \frac{5}{3}\):

velocity According to \(S\): \(\frac{v}{c} = \frac{x_2 - x_1}{ct_2 - ct_1} = \frac{-\frac{V}{c}ct}{ct} = -\frac{V}{c}\)

According to \(S'\): $\( \frac{v'}{c} = \frac{x'\_2 - x'\_1}{ct'\_2 - ct'\_1} = \frac{-2\gamma \frac{V}{c}cdt}{\gamma \left ( 1 + \frac{V^2}{c^2} \right ) ct} = -\frac{4/5}{1+16/25} = -\frac{40}{41}\)$

Thus the magnitude of the velocity according to \(S'\) is less than c.

Newtonian mechanics with GT

E1: \((ct_1, x_1) = (0,0)\) en \((ct_2, x_2) = (ct, -\frac{V}{c}ct)\)

GT:

GT naar \(S'\) with \(\frac{V}{c} = \frac{4}{5}\):

velocity According to \(S\): \(\frac{v}{c} = \frac{x_2 - x_1}{ct_2 - ct_1} = \frac{-\frac{V}{c}ct}{ct} = -\frac{V}{c}\) as before.

According to \(S'\): $\( \frac{v'}{c} = \frac{x'\_2 - x'\_1}{ct'\_2 - ct'\_1} = \frac{-2\frac{V}{c}ct}{ct} = -2\frac{V}{c} = -\frac{8}{5}\)$

Thus the magnitude of the velocity according to \(S'\) is higher than c.

We will come back to this peculiar result in the world of Einstein and Lorentz.