16. Special Relativity - Lorentz Transformation#

As we discussed, in the second half of the nineteenth century it became clear that there was something wrong in classical mechanics. However, people would not easily give up the ideas of classical mechanics. We saw that the luminiferous aether was introduced as a cure and as a medium in which Electromagnetic waves could travel and oscillate. Moreover, Lorentz and Fitzgerald managed to find a coordinate transformation that made the wave equation of Maxwell invariant. Fitzgerald came even up with length contraction: if the arm moving parallel to the aether of the interferometer of Michelson and Morley would contract according to \(L_n = L \sqrt{1-\frac{V^2}{c^2}}\) then, the M&M experiment should result in no time difference for the two paths, in agreement with the experimental findings. However, there was no fundamental reasoning, no physics underpinning the transformation and the length contraction. The proposals worked, but they had an ad hoc character. very unsatisfying for physicists!

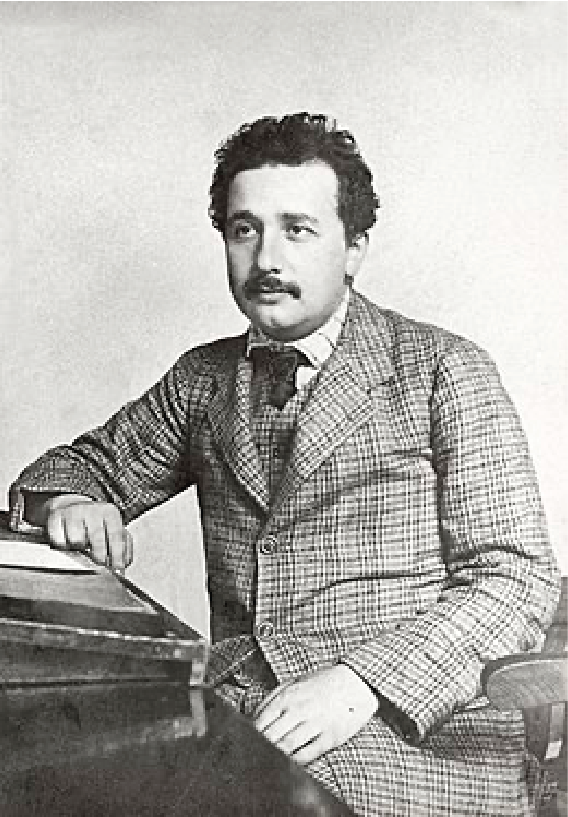

And as we have mentioned, it took the work of a single man to change this and underpin the Lorentz Transformation, making Classical Mechanics a valid limit of Relativity Theory, only applicable at velocities small compared to the speed of light and to small distances compared to those of interest in cosmology.

Fig. 16.1 Albert Einstein (1879-1955). From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.# Lorentz Transformation

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

ct' &= \gamma \left( ct - \frac{V}{c} x \right) \\

x' &= \gamma \left( x - \frac{V}{c} ct \right) \\

y' &= y \\

z' &= z \\

\text{with} \quad \gamma &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{V^2}{c^2}}}

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

This transformation made the theory of Maxwell invariant under translation from one inertial observer to another, keeping \(c\), the speed of light in vacuum, the same for both of them. But there is more! Einstein also changed our view on the universe and on time itself. In the world of Newton and Galilei, people could not even think about relativity of time. Of course time was the same for everyone. There was only one time, one master clock - the same for all of us. It is hard coded in the Galilei Transformation: Galilei Transformation

\[\begin{split}

\begin{split}

t' &= t \\

x' &= x - Vt \\

y' &= y \\

z' &= z

\end{split}

\end{split}\]

Lorentz Transformation

\[\begin{split}

\begin{split}

ct' &= \gamma \left ( ct - \frac{V}{c} x \right ) \\

x' &= \gamma \left ( x - \frac{V}{c} ct \right ) \\

y' &= y \\

z' &= z

\end{split}

\end{split}\]

|

Now, with the Lorentz Transformation, that is no longer true: different observers may have different time. We will see that this has very peculiar consequences, some of which are very counterintuitive. However, they have been tested over and over again. And so far: they firmly hold. And there is no other way then to accept that the world and our universe is different from what we thought and from what we experience in our daily lives.

Do note, that the Galilei Transform is a limit of the Lorenz Transformation. If we let \(c \rightarrow \infty\), we see that \(\gamma \rightarrow 1\) and \(\frac{V}{c} \rightarrow 0\). And this gives us: \(t' = t\) and \(x' = x - Vt\), that is the Galilei Transformation! Now, this should not come as a surprise (even if it for a moment did). Afterall, Classical Mechanics does an outstanding job in many, many physics problems and the agreement with experiments is excellent.

16.1. More on the Lorentz Transformation#

The way we wrote down the Lorentz transformation is a bit particular in the sense that we combine time \(t\) with the speed of light \(c\) into the “time” axis \(ct\) which now has unit length. We can do this as \(c\) is constant for all observers independent of their frame of reference. The speed of light is said to be a Lorentz invariant. In this notation the transform between \(S\) and \(S'\) (moving with velocity \(V\) away) is easy to remember!

16.1.1. S and S’#

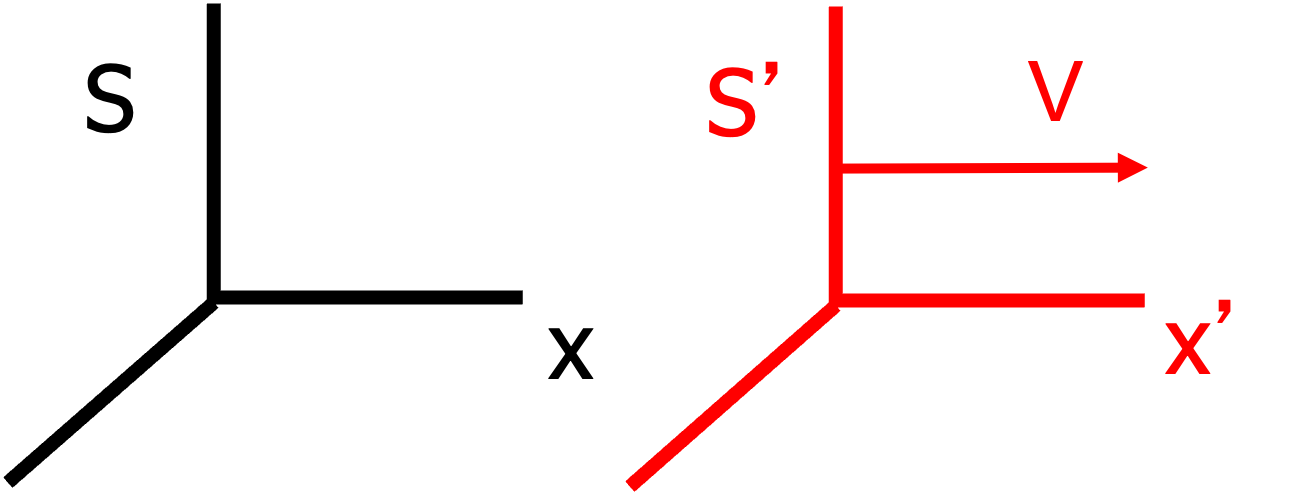

We will discuss most of the consequences for two observers \(S\) and \(S'\), traveling with a constant velocity \(\vec{V}\) with respect to each other. They have taken their \(x\), resp. \(x'\) axis parallel to \(\vec{V}\). Hence, we only need to talk about \(V\), knowing that this is the only component of the relative velocity between the two observers and that it is along the \(x, x'\) axis.

Furthermore, their \(y\) and \(y'\) coordinates are taken in the same direction. This also holds for the \(z\)-component. Finally, when \(S\) and \(S'\) pass each other (they are then both at the same point), they put their clocks to zero: \(t=0\) and \(t'=0\).

Note: \(S\) is sitting in her origin \(\mathcal{O}\) (with coordinates, according to \(S\) (x,y,z)=(0,0,0)) and stays there. Similarly for \(S'\) who is sitting in \(\mathcal{O}'\) (with coordinates, according to \(S'\) (x’,y’,z’)=(0,0,0)).

The standard sketch is given in the figure below.

Fig. 16.2 S and S’: relative velocity parallel to the \(x\) and \(x'\) axes.#

N.B. It is crucial to be very precise in your notation when it comes to coordinates and quantities. For instance: \(S\) might talk about the \(x\)-component of the velocity of an object and denote this by \(v_x\). \(S'\), on the other hand can also talk about that component, but will not call it the \(x\)-component: in the world of \(S'\) \(x\) “does not exist”, only \(x'\) does. So it is better to write \(v'_{x'}\) for the \(x'\)-component of the velocity of the object according to \(S'\). It may look cumbersome, and to a certain extend it is, but it actually does make sense. \(S'\) would say that this component is \(\frac{dx'}{dt'}\) both space and time having a prime. Hence, naturally \(S'\) would talk about \(\vec{r}' = x' \hat{x'} + y' \hat{y'} + z' \hat{z'}\) or \(\vec{v}' = v'_{x'} \hat{x'} + v'_{y'} \hat{y'} + v'_{z'} \hat{z'}\)

16.1.2. Lorentz Transformation and its Inverse#

The Lorentz Transformation, like the Galilei Transformation is a communication protocol for \(S\) and \(S'\). It allows them, the interpret information that they get from each other in their own ‘world’, i.e. coordinate system.

For instance, if \(S\) sees an object moving with \(v_x\), \(S'\) can ‘translate’ this information via the Lorentz Transform into \(v'_{x'}\) and \(v'_{y'}\) or so if applicable. Of course, \(S\) also needs such a translation scheme when receiving information from \(S'\). That is: \(S\) needs the inverse transformation.

Luckily, the inverse is very easy to reconstruct from the Lorentz Transform itself.

After all: its is relativity theory. If \(S\) sees \(S'\) moving at a constant velocity \(V\), then - because motion is relative- \(S'\) will say that \(S\) moves with \(-V\). And thus, if \(S'\) writes down the Lorentz Transformation, she uses \(-V\).

The inverse is therefore given by

with the Lorentz factor \(\gamma(V) \equiv \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{V^2}{c^2}}} \geq 1\).Note that as \(\gamma\) is quadratic in \(V\), both \(S\) and \(S'\) use the same value! That is why we don’t talk about \(\gamma '\): it is equal to \(\gamma\).

The structure of the formulas is very symmetric and therefore needs little remembering.

From the Lorentz transformation it is clear that time is not universal anymore (\(ct'\neq ct\) in general). This is a large step from Newton and Galileo. Now the time coordinated is mixed somehow with the space coordinated depending on the speed \(V\).

16.1.3. Lorentz factor#

The Lorentz factor (or \(\gamma\)-factor)

is a dimensionless constant depending on the ratio of the velocity \(V\) to the speed of light \(c\). Sometimes this ratio \(V/c\) is abbreviated further as \(\beta \equiv \frac{V}{c} \leq 1\). For the ratio we know that it is smaller than 1 as \(c\) is a limit velocity. From that it follows that the \(\gamma\)-factor is always equal to or larger than one, \(\gamma \geq 1\). As we will see later the factor also relates the coordinated time interval \(dt\) to the proper time \(d\tau\), as \(\gamma = \frac{dt}{d\tau}\).

In many exercises the speed \(V\) is given already as fraction of \(c\), e.g. \(V=0.8c\). Analytically only for very few speeds a nice \(\gamma\)-factor is computed. These are

Note that this list goes on for ever: there is a simple rule to find the triplets. Think about it yourself. Hint: the first one uses (3,4,5), the third one (5,12,13). What is special about them? \(5^2 - 4^2 = 5+4 = 3^2\) and \(13^2 - 12^2 = 13 + 12 = 5^2\). Do you see the pattern? Can you derive the general rule? What is the next one? How about (7,24,25)?

16.1.4. In the limit#

In the limit of low speeds with respect to the speed of light \(\frac{V}{c}\ll 1 \Rightarrow \gamma =1\). Practically, this happens for about \(V< 0.1 c \sim 30.000\) km/s. In this limit the Lorentz transformation also reduces to the Galileo transformation.

In the limit of infinity speed of light (\(c\to\infty\)) the \(\gamma\)-factor is again one: \(\gamma=1\) and the ratio \(V/c \to 0\). Also here the LT reduces to the GT. The case of infinite speed of light represents the case that GT is generally valid, i.e. \(c'=c+V\).

It is always important to verify that an extension of the known theory reduces to the known theory that has proved itself for most circumstances.

16.2. Derivation of the Lorentz Transformation#

The derivation we give is a bit more detailed in the steps than the once given by Einstein himself in Über die spezielle und allgemeine Relativitätstheorie. The book is written such that it can be followed easily with high-school math, but is nevertheless quite some work (as is this derivation).

We start by the axiom that the speed of light is the same constant for all observers.

We have observers \(S\) and \(S'\), where \(S'\) moves away from \(S\) with velocity \(V\). Consider a light wave traveling in the positive \(x\)-direction which is describe in both systems as \(x-ct=0\) or \(x'-ct'=0\). NB: In 3D a light wave is described by \(x^2+y^2+z^2-(ct)^2=0\) which reduced to \(x-ct=0\) in 1D.

Therefore the transformation relating both systems must be of the form (with \(\lambda\) a real constant)

If we consider a light wave traveling in the negative \(x\)-direction then, it is described in both systems as \(x+ct=0\) and \(x'+ct'=0\) and we need a relation of the form (with real constant \(\mu\))

Next, we add both equations \((*)+(**)\) which gives

If we subtract the two equations \((*)-(**)\)

For convenience we redefine the two constants here \(a=\frac{\lambda+\mu}{2}, b=\frac{\lambda-\mu}{2}\) and the transformation takes the form

Now we consider that the relative speed is \(V\). Thus \(S\) will describe the motion of \(\mathcal{O}'\), that is the origin of \(S': x'=0\), as \(x_{\mathcal{O'}} = Vt\).

However, from the second equation of our transfomation just above, we get for \(\mathcal{O}'\) \(x' = 0 = ax - bct \rightarrow x = \frac{bc}{a}t\). The velocity of \(S'\) with respect to \(S\) is thus \(V=\frac{bc}{a}\). We use this to eliminated the constant \(b=\frac{V}{c}a\) by taking in the velocity.

Now we need only to find the constant \(a\).

We therefore consider a rod of length 1 that is at rest in frame \(S'\) as seen from \(S\), thus we have \(\Delta x'=1\) on time point \(t=0\). Using equation \((\#\#)\) we obtain therefore \(\Delta x=\frac{1}{a}\quad (+)\).

We also consider a rod of length 1 that is at rest in frame \(S\) as seen from \(S'\). For \(t'=0\) we have \(0=a(ct-\frac{V}{c}x)\) from equation \((\#)\). From equation \((\#\#)\) we have \(act=\frac{c}{V}(ax-x')\). Putting both equations together we have

Now we invoke the relativity principle that the interval given by equation \((+)\) and \((++)\) must be the same for both observers! This means that there is no preferential observer and what holds for one must hold for the other, as by axion 1.

The constant \(a\) has been eliminated and replaced by the ratio of the relative velocity \(V\) and the speed of light \(c\). As this is a complicated factor we write short hand \(\gamma\) for it. Now we have arrived at the Lorentz transformation

For the inverse transformation, if you want \(ct,x\) explicitly instead of implicitly the transformation reads

The easiest way to see this (without solving the math explicitly), is to think \(ct',x' \to ct,x\) and therefore \(V\to -V\).

Please notice that somehow it was natural to consider the time axis as \(ct\) (instead of \(t\)) which is of course a length unit not a time unit. Later we see that this allows calculations in spacetime (nearly) with vectors as you are used to as the units of all coordinates are in meters.

16.2.1. Historical context#

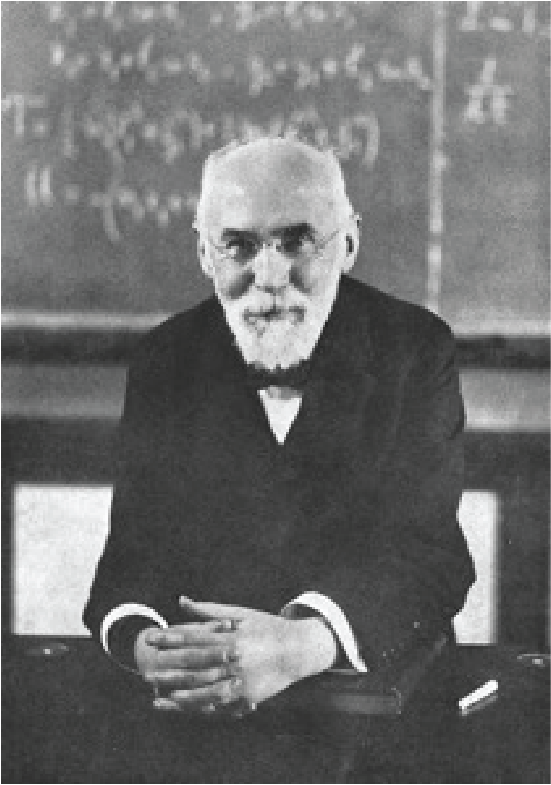

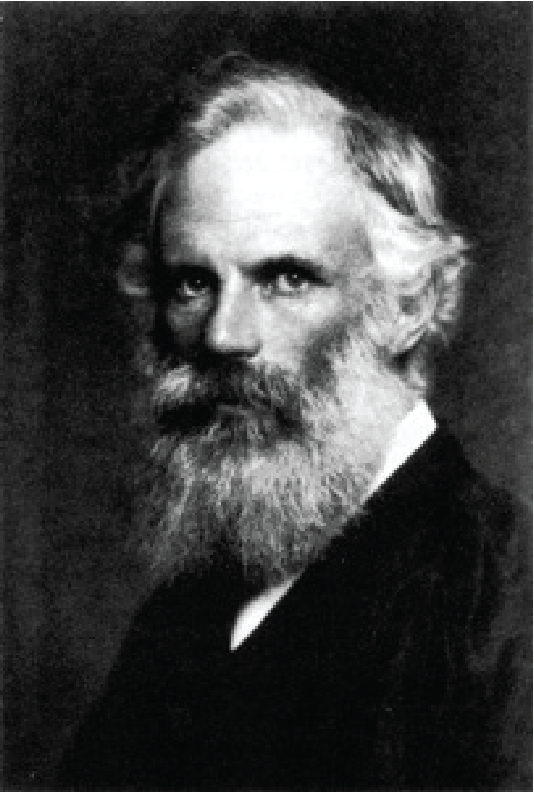

Lorentz did not derive the transformation that now has his name, based on the same ideas as we did here starting from Einstein’s axioms. Lorentz, however, saw that Maxwell’s equations were not GT invariant, therefore he tried to find a transformation under which they were invariant. He did so (with a bit of help from Poincaré afterwards). FitzGerald did also derive the transformation, but too did not understand its implications.

Fig. 16.3 Hendrik Lorentz (1853-1928). From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.# |

Fig. 16.4 George Fitzgerald (1851-1901). From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.# |

Before Einstein’s idea spread, Lorentz thought about the transformation as a fix to Galileo Transformation. Later he understood, of course. Unfortunately, Fitzgerald did not live long enough to see the first publication of Einstein on Relativity in 1905.

16.3. The wave equation is Lorentz invariant#

The Navier-Stokes equation was Galileo invariant as shown earlier, but the Maxwell equations not. Here we will show that the wave equation is Lorentz invariant. It is also clear that the Navier-Stokes equation is then not correct for high speeds as it is not Lorentz invariant.

We remember that we need to transform the second derivatives of \(S\) with respect to space and time to the new coordinates of \(S'\) as the wave equation for the field \(\phi(x,y)\) is \(\frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2}\phi(x,t) =\frac{1}{c^2}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2}\phi(x,t)\).

The old derivatives expressed in the new coordinates of \(S'\) are

Applying the partial derivative twice we arrive at

If we fill in these derivative in the wave equation, we see that the factor \(1/c^2\) on the side of the second time derivative cancels out the mixed term. In addition we see, that each term has \(\gamma^2\) in front which we can cross out. Now we sort all spatial derivatives to one side, and all time derivatives to the other side. We remain with

The wave equation is Lorentz invariant, with constant speed of light \(c=c'\). From this derivation we also see that the value of the \(\gamma\) factor is not relevant for the Lorentz invariance as it cancels out in the derivatives.

The Maxwell’s equations as a whole are Lorentz invariant, which you can now prove yourself if you have the time.

In the coming chapters we will explore the consequences of our new Transformation.