4. Work & Energy#

4.1. Work#

Work and energy are two important concepts. Work is defined as ‘force times path’, but we need a formal definition:

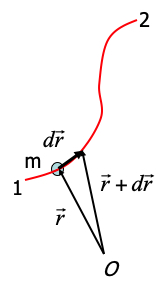

Fig. 4.1 Path of a particle.#

Work

If a point particle moves from \( \vec{r}\) to \( \vec{r} + d\vec{r}\) and during this interval a force \(\vec{F} \) acts on the particle, then this force has performed an amount of work equal to:

\( dW = \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} \)

Note that this an inner product between two vectors, resulting in a scalar. In other words, work is a number, not a vector. It has no direction. That is one of the advantages over force.

Work done on \(m\) by \(F\) during motion from 1 to 2 over a prescribed trajectory:

Keep in mind: in general the work depends on the starting point 1, the end point 2 and on the trajectory. Different trajectories from 1 to 2 may lead to different amounts of work.

4.2. Kinetic Energy#

Kinetic energy is defined and derived using the definition of work and Newton’s \( 2^{nd} \) Law.

The following holds: if work is done on a particle, then its kinetic energy must change. And vice versa: if the kinetic energy of an object changes, then work must have been done on that particle. The following derivation shows this.

It is from the above that we indicate \(\frac{1}{2}m\vec{v}^2\) as kinetic energy. It is important to realize that the concept of kinetic energy does not bring anything that is not contained in N2 to the table. But it does give a new perspective: kinetic energy can only be gained or lost if a force performs work on the particle. And vice versa: if a force performs work on a particle, the particle will change its kinetic energy.

Kinetic Energy

If work is done on a particle, then its kinetic energy must change. And vice versa: if the kinetic energy of an object changes, then work must have been done on that particle.

\( \Delta E_{kin, 12} = W_{12} \)

Obviously, if more than one force acts, the net work done on the particle determines the change in kinetic energy. It is perfectly possible that force 1 adds an amount \( W \) to the particle, whereas at the same time force 2 will take out an amount \( -W \). This is the case for a particle that moves under the influence of two forces that cancel each other: \( \vec{F}_1 = -\vec{F}_2 \). From Newton 2, we immediately infer that if the two forces cancel each other, then the particle will move with a constant velocity. Hence, its kinetic energy stays constant. This is completely in line with the fact that in this case the net work done on the particle is zero:

4.3. Worked Examples#

Example 4.1 Carrying a weight

You carry a heavy backpack \(m\) =20 kg from Delft to Rotterdam (20 km). What is the work that you have done against the gravitational force?

Solution 4.1

The answer is, of course, zero! That is because the path (from Delft to Rotterdam) is perpendicular to the gravitational force. Therefore the inner product \(\vec{F}\cdot d\vec{r}=0\) over the whole way. Let us look at it more formally, this will help us when things get more complicated later.

The force is \(\vec{F}(x,y,z)=(0,0,-mg)=-mg\hat{z}\) and we choose our coordinate system such that the path be along the \(x\)-axis, the \(y\)-coordinate is zero and we the backpack is at height \(z=1\) m.

Example 4.2 Work in a force field

Now we consider a force field \(\vec{F}(x,y)=(-y,x^2)=-y \hat{x} +x^2 \hat{y}\). We compute the work done over a path from the origin \((0,0)\) to \((1,0)\) and then to \((1,1)\) first along the \(x\)-axis and then parallel to the \(y\)-axis.

Solution 4.2

We can split up the integral in these two parts as the direction in both parts is constant, therefore the inner product can be separated out.

Try to integrate the force field yourself along a different path \((0,0)\to(0,1)\to(1,1)\) to the same end point.

The work done is the same over this path too. This could be coincidence or the case for any path. You will learn how to check this in the next chapter on potential energy.

Reminder of path/line integral from Calculus

As long as the path can be split along coordinate axis the separation above is a good recipe. If that is not the case, then we need to turn back to the way how things have been introduced in the Calculus class. We need to make a 1D parameterization of the path.

Line integral of a vector valued function \(\vec{F}(x,y,z): \mathbb{R}^3\to\mathbb{R}^3\) over a curve \({\cal{C}}\) is given as

We integrate in the definition of the work from point 1 to 2 over an implicitly given path. To compute this actually, you need to parameterize the path by \(\vec{r}(\tau )=(x(\tau), y(\tau), z(\tau))\). The integration variable \(\tau\) tells you where you are on the path, \(\tau \in [a,b]\in\mathbb{R}\). The derivative of \(\vec{r}\) with respect to \(\tau\) gives the tangent vector to the curve, the “speed” of walking along the curve. In the calculus classes you used \(\vec{v}(\tau)\equiv \frac{d \vec{r}(\tau)}{d\tau}\) for the speed. The value of the line integral is independent of the chosen parameterization. However, it changes sign when reversing the integration boundaries.

Example 4.3

Straight line

Now we integrate from \((0,0)\to(1,1)\) but along the diagonal. A parameterization of this path is \(\vec{r}(\tau) = (0,0)+(1,1)\tau = (\tau, \tau), \tau\in [0,1]\). The derivative is \(\frac{d \vec{r}(\tau)}{d\tau}=(1,1)\). Therefore we can write the work of \(\vec{F}(x,y)=-y \hat{x} +x^2 \hat{y}\) along the diagonal as

Parabola

Integration of the same force \(\vec{F}(x,y)=-y \hat{x} +x^2 \hat{y}\) from \((0,0)\to(1,1)\) but along a normal parabola. A parameterization of the path is \(\vec{r}(\tau)=(0,0)+(\tau,\tau^2), \tau\in[0,1]\) and the derivative is \(\frac{d\vec{r}}{d\tau} = (1,2\tau)\). The work then is

4.4. Simulations#

Below is a physlet showing the relation between work done by a constant force and kinetic energy of a particle. Can you understand the curves plotted?

4.5. Exercises#

Here are some more exercises that deal with forces and work. Make sure you practice IDEA.

Exercise 4.1

A point particle (mass \(m\)) drops from a height \(H\) downwards. It starts with zero initial velocity. The only force acting is gravity (take gravity’s acceleration as a constant).

Set up the equation of motion (i.e. N2) for \(m\).

Calculate the velocity upon impact with the ground.

Calculate the kinetic energy of \(m\) when it hits the ground.

Calculate the amount of work done by gravity by solving the integral \(W_{12} = \int_1^2 \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r}\).

Show that the amount of work calculated is indeed equal to the change in kinetic energy.

Solve this exercise using IDEA.

Click here for the solution.

Exercise 4.2

A hockey puck (\(m\) = 160 gram) is hit and slides over the ice-floor. It starts at an initial velocity of 10 m/s. The hockey puck experiences a frictional force from the ice that can be modeled as \(-\mu F_g\) with \(F_g\) the gravitational force on the puck. The friction force eventually stops the motion of the puck. Then the friction is zero (otherwise it would accelerate the puck from rest to some velocity :smiley: ). Constant \(\mu = 0.01\).

Set up the equation of motion (i.e. N2) for \(m\).

Solve the equation of motion and find the trajectory of the puck.

Calculate the amount of work done by gravity by solving the integral \(W_{12} = \int_1^2 \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r}\).

Show that the amount of work calculated is indeed equal to the change in kinetic energy.

Solve this exercise using IDEA.

First try it yourself (and try seriously) before peeking at the solution.

Exercise 4.3

An electron (mass m, charge -e) is in a static electric field. The electric field is of the form \( \vec{E} = E_0 \sin \left ( 2\pi \frac{X}{L} \right ) \hat{x} \). As a consequence, the electron experiences a force \( \vec{F} = -e\vec{E} \)

Due to this force, the electron moves from position \( x=\frac{1}{4}L \) to \( x=0 \).

- Calculated the amount of work done by the electric field.

- Assuming that the electron was initially at rest, what is the velocity at \( x=0 \)?

Click here for the solution.

Exercise 4.4

A force \( F = F_0 e^{-t/\tau} \) is acting on a particle of mass m. The particle is initially at position \( x=0 \). It is, starting at \(t=0\), moving at a constant velocity \(v_0 > 0\) to \(x = L, (L>0) \).

a. Calculate the amount of work done by \(F\).

b. The amount of work done is equal to the change in kinetic energy. However, the particle doesn’t change its kinetic energy. Why is this general rule not violated in this case?

You can check you answers here