1. From Geocentric to Heliocentric#

1.1. Geo-centric or Helios-centric?#

Imagine that you have never heard of the modern concept of our solar system or about galaxies and all kind of other concepts of cosmology. So, picture yourself in the ancient days of the Greek, Babylonian, Egyptian or Chinese civilization. During the dark nights, when the sky was open, you would be staring at the unknown above you, trying to figure out what that is all about. What would your idea be?

Fig. 1.1 Plato. From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.# |

Fig. 1.2 Aristotle. From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.# |

Not surprising for a long time, people thought of the earth as a flat disk. It does look that way if you look around. The curvature is hardly felt and only seen when you are at a beach, looking over the ocean. Moreover, what would you guess from what you see: the sun and stars ‘looping’ in half a day from east to west. Every day in the same rhythm. I for myself, I wouldn’t be surprised if I thought that the earth was the center of it all, with alle ‘heavenly bodies’ moving in big circular motion around us, here at earth. I probably, would not doubt the idea that the universe is eternal, never changing and working like a clock.

And, I probably would also ‘buy the idea’ of the Greek philosophers, that the heavens are made of different spheres. The sphere and circle being the most perfectly symmetrical figures. For which it is easy to think in terms of eternal motion, clock work and divine origin. The great Greek thinkers (Fig. 1.1), Plato (~425 - 348/347 BC) and his pupil Aristotle (384-322 BC) wrote extensively about the universe: how it worked, how its ordening could be seen. The fundamental idea is that of the earth in the center of the universe and all other celestial bodies moving around the center in circles positioned on discrete, separate spheres.

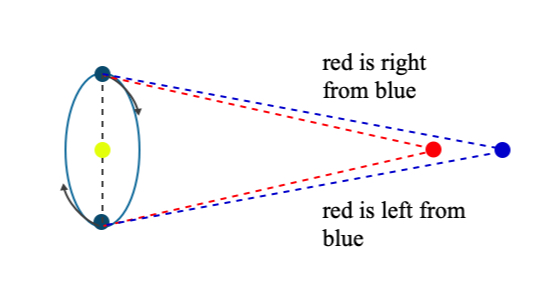

One might wonder: could they, in the ancient days, not have found clues that the earth is not the center around which everything rotates? Well, yes and no. They could have looked for instance for parallax, that is the apparent change in position when you look at distant objects from two different locations. We now know that in half a year the earth has moved substantially. So, you might expect that objects that are not at the same distance will have a different, apparent displacement and therefore their relative position will change. But, that is not what we over the course of a year observe.

Fig. 1.3 Parallax: apparent change in position caused by motion of the earth.#

The stellar constellations, like the Big Dipper, stay the same. Again, with our present day knowledge, that is not surprising: the stars are so far away that their parallax is really small. Moreover, in the life span of a human, the motion of the various stars in e.g. the Big Dipper seems to be as if they are somehow fixed to each other. Only on astronomical time scales, we would observe that the stars in the Big Dipper move completely independent. From the seven stars that form the Big Dipper, five are at roughly the same distance from us (~ 80 light year). They move as a group around the center of our galaxy. The other two are much further away from us (104 and 124 light year, resp.). They orbit at a different speed around the center of the galaxy. In the long run, this will completely distort the shape of the Big Dipper as we see it currently. But in the long run, really means in the long run. Our sun, for instance, takes 225 million years to go round its orbit once. Hence, during the time scale of humans and their civilization not much has changed in the relative positions of the stars.

© American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY; approval pending.

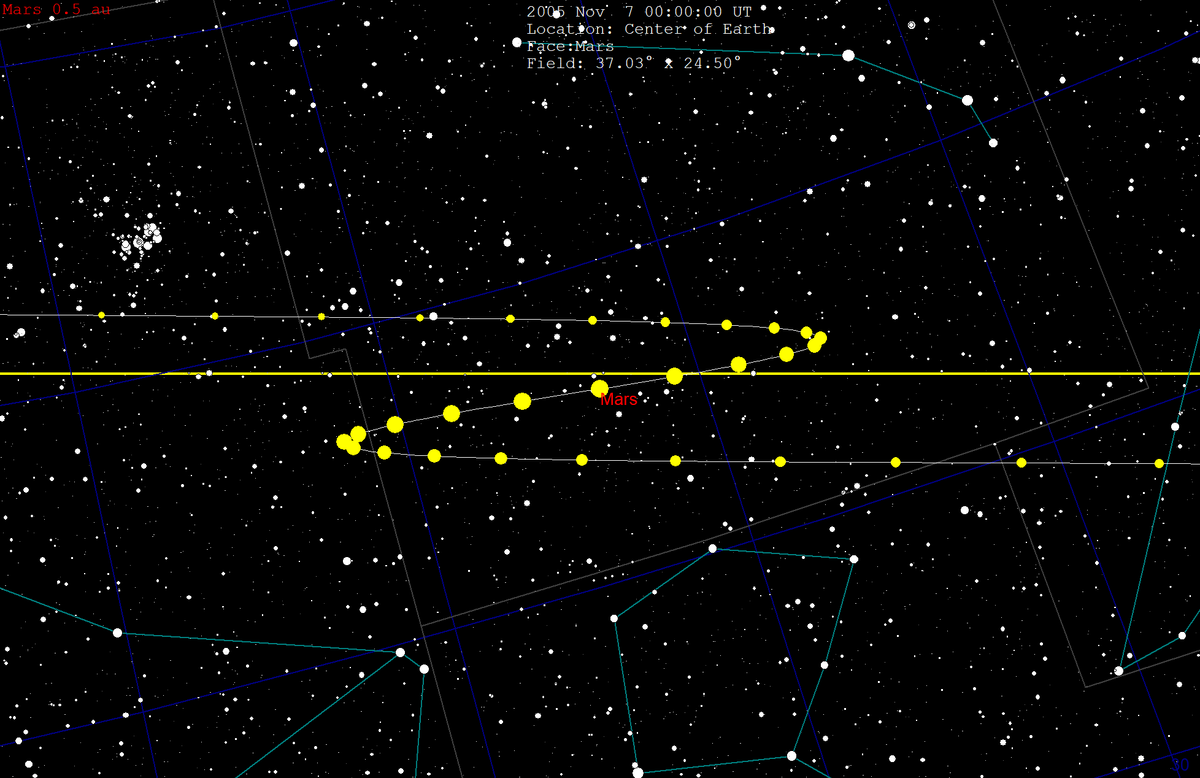

Nevertheless, the idea of the earth at the center of the universe and everything else rotating around it in circular orbits that are part of a small number of different spheres had its problems. The motion of the planet Mars along the sky isn’t exactly like it is moving at a constant speed over a fixed circle. It sometimes is moving backwards. Fig. 1.4 shows the position of Mars over a period of several month, that is, after every few days the position of Mars is shown against the night sky at the same time at night. Mars is moving relative to the stars. But not at a constant speed. It even reverses its direction for a short while.

Fig. 1.4 Position of Mars versus the ‘fixed stars’ over a longer period of time. Mars seems to move backwards for a short period of time. From Wikimedia Commons by Tomruen, licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0.#

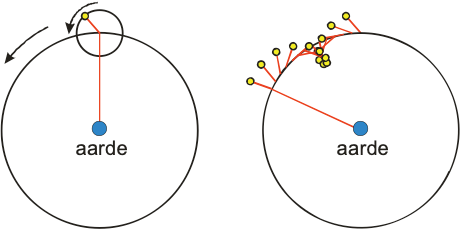

The Greek astronomers and philosophers ‘cured’ this mismatch with the circle & sphere idea by introducing epi-cycles. That is, Mars itself was orbiting in a circular motion around a point on the main circle. The latter was moving at a constant speed over its circle. Fig. 1.5 shows what this is and how that can lead to backward motion.

Fig. 1.5 Epi-cycles and the moving backwards of a planet.#

From the Helio-centric view, one can easily compute the geo-centric one and find that indeed the apparent motion of Mars will revert. A little animation is given in the video below.

Fig. 1.6 Sun (yellow), Earth (blue) and Mars (red). Left: helio centrum view; right: geo centric view.#

A nice YouTube video from the BBC can be seen here. We now know, that this apparent change of direction of motion is caused by both Mars and the earth rotating around the sun. The Greek astronomer Ptolemy (100-170 AD) worked out a system with epi-cycles. According to him, the large circle around which Mars’ smaller circle was moving, did not have its center at the middle of the earth, but it was displaced. He had to break with the idea that the earth was the center of all motion. At Ptolemy’s time, the predictions from his system were pretty accurate. But that was at the expense of simplicity: he had to use 80 epi-cycles to capture the motion of the sun, moon and Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. The idea of the Greeks would last for centuries, until around 1400 AD on different parts of the world the conclusion was reached that a helio-centric view was a much better representation of the universe.

Already as early as in the third century BC, it was proposed that the earth was not steady. Aristarchus of Samos (~310 - ~230 BC) is seen as the first one to propose that the earth rotates once a day around its axis. This causes the apparent motion of the sun and all other planets and stars as we seem to observe. Moreover, he also proposed that the earth was orbiting the sun in one year. His ideas were rejected and the geocentric view of Aristotle and Plato prevailed for a long time. Aristarchus’ work did not survive in written form. We know of his ideas through the writings of Archimedes. It is also believed that Nicolaus Copernicus was aware of some of the ideas of Aristarchus, but probably not that he advocated a helio-centric view.

1.2. Mohammed Ulugh Bek#

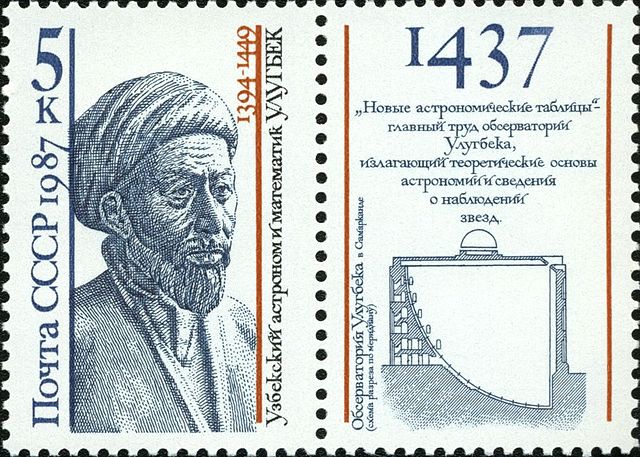

In the Muslim world astronomers also studied the motion of stars and planets. A good knowledge of times especially the lunar motion and position is important to Muslims, as their daily prayers and various other religious festivals and celebrations follow the lunar calendar. In the Islamic Golden Age, science and especially mathematics and astronomy reached a high level. While in Europe large parts were still in the dark part of the early Middle Ages, Islamic scientists studied the skies at night. Already in the 11\(^{th}\) some reached the conclusion that the earth is rotating around its axis and is not the center of the universe. In the first half of the 15\(^{th}\) century, Ulugh Beg (1394-1449, ruler of the Timurid Empire) built a large Observatory in Samarkand. Since the telescope was yet to be discovered, he worked with traditional instruments, like the sextant. To increase the accuracy, his observatory contained a sextant with a radius of 36m. It allowed him to improve the star catalogue of Ptolemy.

Fig. 1.7 Stamp with portrait of Ulugh Beg and Inside Ulugh Beg’s observatory. From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.#

One of the scientists working at the Samarkand Observatory was Ali Quashji (1403-1474). He opposed the ideas of Aristotle on physics and tried to make astronomy an empirical and mathematical science. From studying the motion of comets, he found empirical evidence that the earth is spinning. He also argued that astronomers didn’t need to follow Aristotle’s theory of heavenly spheres and circular motion. The work at Samarkand and other places in the Islamic world was moving away from the Greek philosophy into the direction of what we would call modern science. They had ideas about a helio-centric view of the universe and a moving earth. It would take another hundred years before in Europe, Nicolaus Copernicus would postulate that the earth is orbiting the sun and not the other way around.

1.3. Nicolaus Copernicus#

Meanwhile in Europe, the Catholic church still had a firm grip on scientific ideas. The geo-centric view prevailed. It was unthinkable that the earth was not the center of the universe. Anybody questioning this or similar ideas had a fair chance of ending on the pyre. Nevertheless, also in Europe the geo-centric model started eventually to crumble.

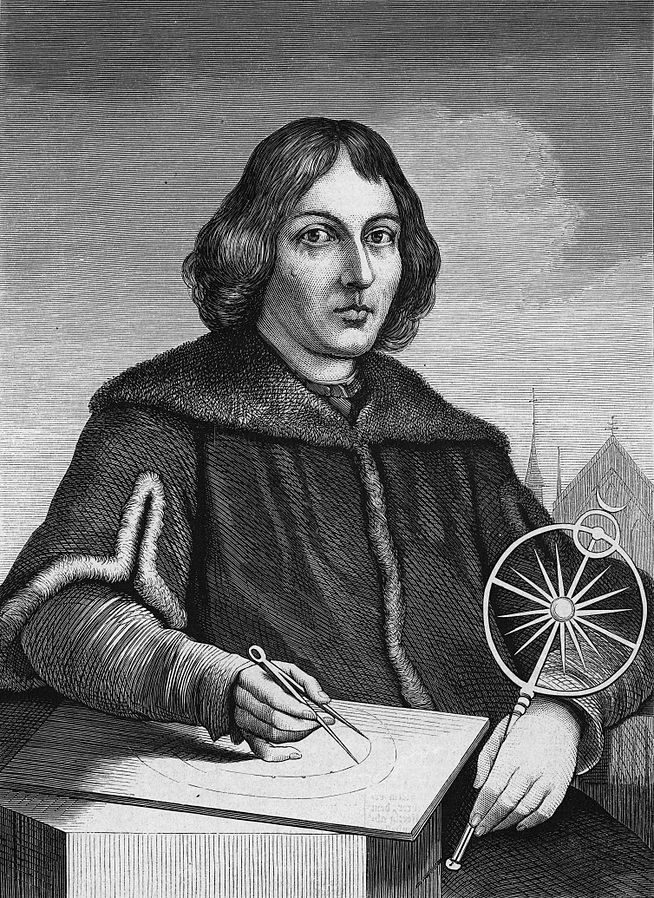

Fig. 1.8 Nicolaus Copernicus holding a helio-centric model in his hand. From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.#

The Polish astronomer and mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) is credited to start the revolution towards a helio-centered universe in Europe. Copernicus, born in Thorn (Poland), was a mathematician and astronomer. After studying at Krakow University, he spend some years in Italy where he completed his studies. Subsequently he moved back to Poland, where he would spend the rest of his life.

Copernicus finished more or less his work on the helio-centric view in 1532, when he completed his manuscript De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. He did not publish it as he feared public reaction and mock for his far reaching ideas. Nevertheless, his ideas reached the pope, who was rather interested. Only at the end of his life, Copernicus agreed to have his book published. He passed away in 1543, when the book printing was still on its way.

1.4. Galileo Galilei#

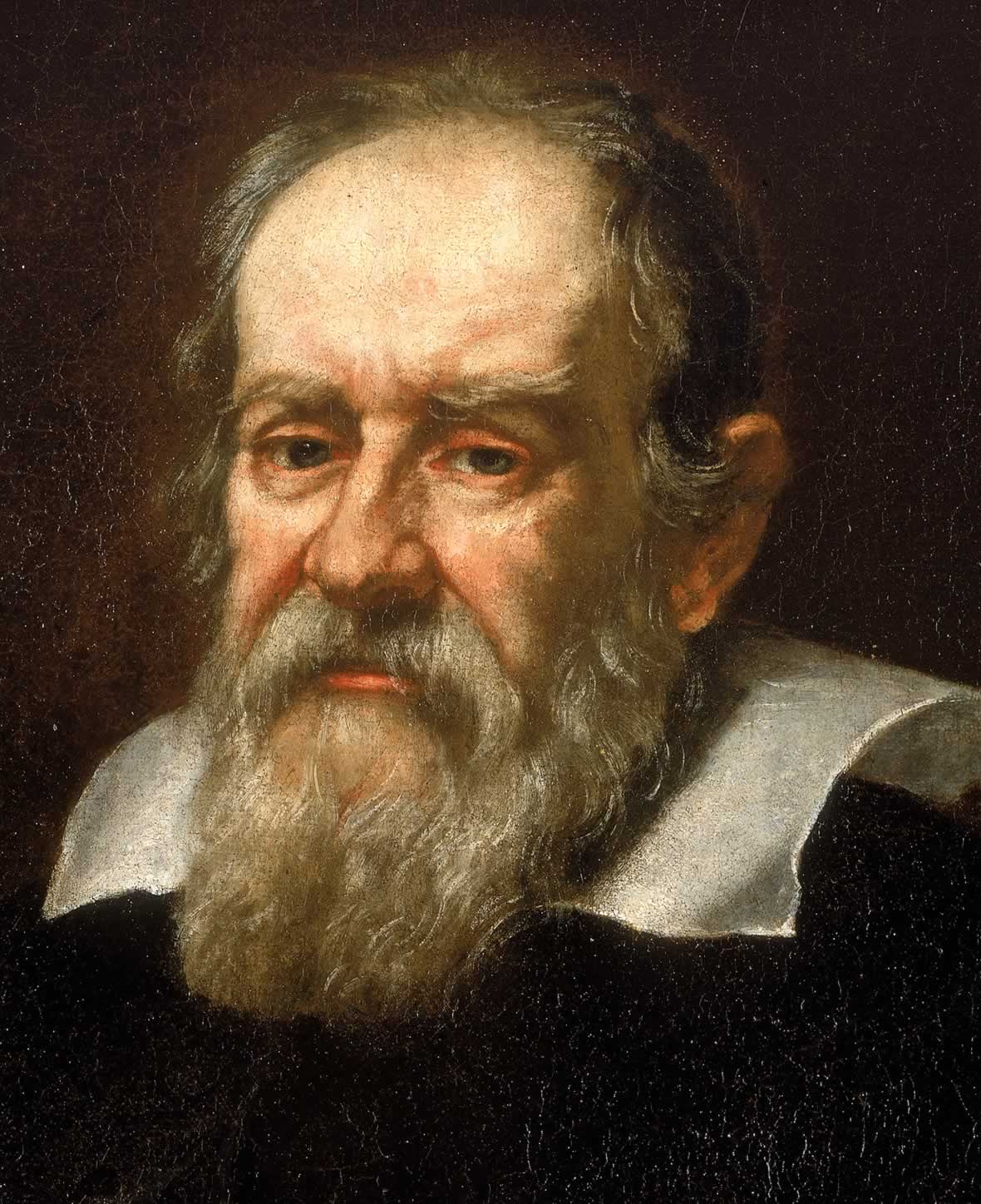

Galileo Galilei (Pisa, Italy, 17 Feb. 1564 - Florence, Italy, 8 Jan. 1642) is seen as one of the founding fathers of experimental physics and with that of modern science. He pioneered with falling object and reasoned that the acceleration of falling objects is independent of their mass. The story is that he performed an experiment by dropping two unequal masses from the leaning tower of Pisa, showing that they reached the ground at the same time. It is probably not true, but Galilei had a splendid thought experiment to show it couldn’t be otherwise.

Fig. 1.9 Portrait of Galileo Galilei in 1636 A.D. by Justus Sustermans. From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.#

Galilei reasoned as follows. Suppose we have two masses \(m_1 > m_2\). If objects of greater mass drop faster (as Aristotle believed) the \(m_1\) will be quicker at the ground than \(m_2\). However, connect \(m_2\) to \(m_1\), say with a small piece of rope. Then, \(m_2\) will slow down \(m_1\) as it cannot accelerate at the same rate. But the combination of \(m_1 + m_2\) has a mass higher than that of \(m_1\). Consequently it should have a higher acceleration. These statements can not both be true. The only way out is all objects experience the same acceleration due to gravity.

Obviously, with our modern knowledge, we can refine this idea by taking air friction into consideration. That will change part of the argumentation and the general conclusion reached above will no longer be valid. But, that wasn’t Galilei’s claim. He considered the effect of gravity only and ignored friction. So, in our terminology, he considered two masses falling through vacuum with the only force acting, gravity.

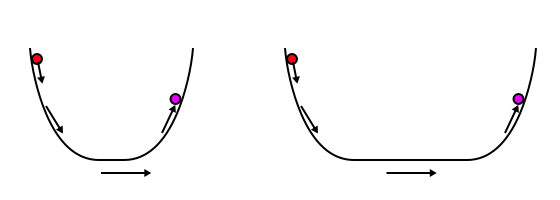

Galilei had another thought experiment. Suppose, we have a kind of curved gutter from which we can release a particle as shown in (Fig. 1.10). The particle starts high and, under the influence of gravity, will accelerate downhill picking up speed. It will move to the right side and climb up the gutter. Its speed will reduce until eventually it reaches its highest point at the right side. In our modern terminology, we could describe this by the particle changing potential energy for kinetic energy on the downward way and vice versa will moving upwards. If friction can be ignored, the particle will reach the same height as it was released from, but now on the other side of the gutter. Galilei reasoned: if we widen the ‘valley’, still the particle will reach the same height if we ignore friction. Consequently, if we make the ‘valley’ infinitely wide, the particle will have to keep moving as eventually it should reach the other side and climb up. But then, in the horizontal part, its velocity can not decrease as then it would ultimately come to a stand still and it will not reach the same height on the other side. This led Galilei to his law: if no force is applied to a particle, it will continue to move at a constant speed. This law is also know as the Law of Inertia.

Fig. 1.10 Galilei: a particle moving down the gutter will reach the same height at the other side.#

Now, this may seem trivial to us, but here Galilei breaks with the prevailing ideas that particles (or matter) move naturally to the earth as that is their natural place. From Galilei’s idea we have to conclude that there is no natural place where particles are drawn to.

Galilei also was a firm believer of Copernicus helio-centric ideas. It brought him in conflict with the Catholic Church. He was forced to appear in front of the Inquisition. Galilei was in his time already one of the most influential scientists. That probably saved him from the death penalty. In stead he was sentenced to formal imprisonment, which was the next day changed to house arrest. But Galilei never took back his ideas. According to a popular legend, he muttered “and yet it moves” at the end of his trial.

Galilei has a longer track record of inventions and discoveries. In 1608, the Dutch lens maker, Johannes Lipperhey (1570-1619) developed the first telescope. Soon, Galilei got hold of this new idea and made one himself. His first one had a magnification of 3, but in later versions improved it to about 30x magnification. With his telescope he observed the moon and saw that it was anything but a smooth sphere. He saw lunar craters and mountains.

In 1610 Galilei was observing Jupiter and found that it had not one but four moons! Yet another proof to him, that the geo-centric view of Plato and Aristotle couldn’t be true. These moons were clearly orbiting Jupiter, in much the same way as our moon did around the earth. Galilei also noticed that Venus exhibits phases, much like our moon does. He concluded that that must mean that Venus is in an orbit around the sun and not as previously thought always ‘on the inside’ of the solar path around the earth. Yet another argument in favour of the helio-centric view. Galilei studied the sunspots. They turned out to be changing, showing that the sun isn’t a perfect , never changing object: another blow to the ancient geo-centric view. He also turned his telescope to the stars, to realise that in contrast to the general believe, the Milky Way wasn’t some kind of ‘nebulous’, but instead an extremely large collection of stars packed closely together is a band. The list of discoveries and innovations goes on and on, just as an example, Galilei figured out that the period of oscillation of a pendulum does not depend on the weight that is suspended.

In 1992 pope John Paul II acknowledged that the church had made a mistake in condemning Galilei. The pope apologised and publicly announced that Galilei was right; there was no reason to doubt Galilei’s faith in God.

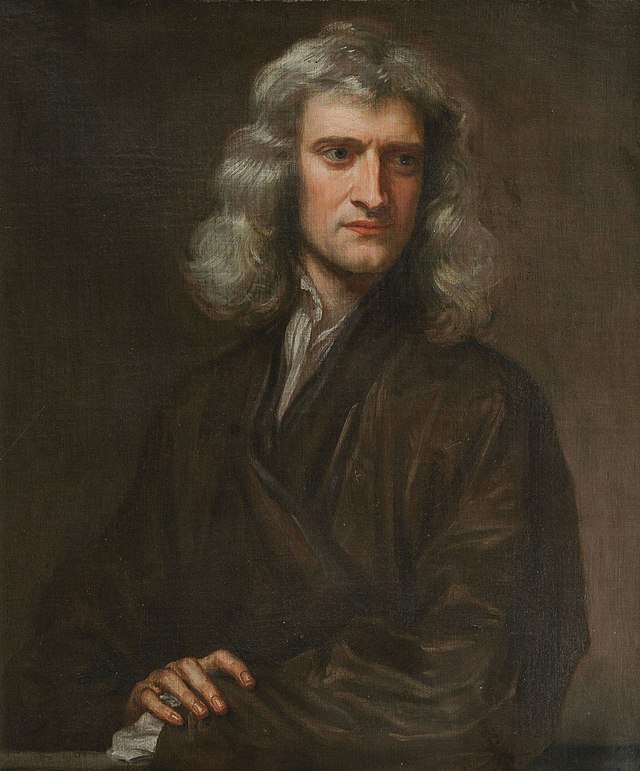

1.5. Isaac Newton#

At the end of the year of Galilei’s death, Isaac Newton was born in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth in England. He is regarded as the founder of classical mechanics and with that he can be seen as the father of physics.

Fig. 1.11 Isaac Newton (1642-1727). From Wikimedia Commons, public domain.#

In 1661, he started studying at Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1665, the university temporarily closed due to an outbreak of the plague. Newton returned to his home and started working on some of his breakthroughs in calculus, optics and gravitation. Newton’s list of discoveries is unsurpassed. He invented calculus (at about the same time and independent of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)). Newton is known for ‘the binomium of Newton’, the cooling law of Newton. He proposed that light is made of particles. And he formulated his law of gravity. Finally, he postulated his three laws that started classical mechanics and worked on several ideas towards energy and work. Much of our concepts in physics are based on the early ideas and their subsequent development in classical mechanics. The laws and rules apply to virtually all daily life physical phenomena and only do they require adaptation when we go the very small scale or extreme velocities and cosmology. In what follows, we will follow his footsteps, but in a modern way that we owe to many physicist and mathematicians that over the years shaped the theory of classical mechanics in a much more comprehensive form. We do not only stand on shoulders of giants, we stand on a platform carried by many.