One Random Variable#

Consider a river that is protected by dikes, earthen embankments with the purpose of keeping water in the river channel and preventing flooding of the hinterland. The dikes should be designed and build such that the height allows the river to safely pass the maximum discharge every year, measured in m\(^3\)/s. A rating curve (Fig. 1) gives us the relationship between discharge and water depth, \(h_w\), so if we know what the maximum discharge is, we can build our dikes to the critical height, \(h_{dike}\geq h_w\). But there is a problem—what is the maximum discharge in the river each year? How would we even go about determining this value? One way is to make observations and find the highest recorded data point. For example, in 1995 the Rhine River reached a discharge of around 12,000 m\(^3\)/s, the highest recorded level to date. But even with over 100 years of measurements, the record is not complete: there could always be a bigger discharge. Another approach could be to come up with a number that is, beyond a reasonable doubt, impossible to exceed. Many experts believe that 16,000 m\(^3\)/s is getting close to an upper limit, and 20,000 m\(^3\)/s may be physically impossible. Which of these two values should we choose for the design of our dike, and why?[1]

Fig. 1 Rating curve for hypothetical river. Relationship is \(q=C \cdot h_w^\beta\) where \(\beta\)=2.0 and \(C\)=4.0.#

This is a difficult question because the actual discharge observed in a given year is random. In addition to other variables, it is largely dependent on rainfall in the drainage basin, which is impossible to predict far in advance—certainly not for the entire year. Furthermore, we don’t have a way to accurately extrapolate our past observations to identify a logical maximum discharge. For this reason, we will use a continuous probability distribution to quantify the probability associated with a specific maximum discharge, \(q\), that might be observed in a given year, defined by the PDF \(f_{Q}(q)\) and CDF \(F_{Q}(q)\). The only other piece of information needed is a design standard—a probability that defines the discharge to use for our design. Other chapters in this book cover the derivation of a design standard, so for this discussion we will assume that a flooding probability of 1/100 has already been determined as the acceptable level. Because there is only one random variable, we can use the PDF to determine the design discharge (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 PDF and design value for river discharge with 0.01 probability of exceedance: \(q_{design}=155 \: \text{m}^3\text{/s}\).#

In particular, we note that failure occurs for high discharge, so we must use the complementary CDF to find the design value, in this case probability of exceeding \(q_{\mathrm{design}}\):

after which the water depth and minimum dike height can easily be determined from the rating curve:

Recalling the safety margin limit state from the previous section, \(M=R-S\), we can see that randomness plays a role through the load variable, \(S\), such that

If the condition \(M<0\) defines flooding (i.e., failure) and if \(q\) is the only random variable, we have successfully ensured a situation where the flooding probability is 0.01.

Reflection on the Simple Example

Is this an oversimplification of reality? Perhaps, but it gets pretty close. Many flood protection systems in the world use an exceedance proabability approach to probabilistic design: choosing a specific and making sure the component or system can handle the load. This works well when the primary source of uncertainty is the load: the river discharge in this case.

We also took for granted that a simple relationship between river discharge and water depth is available. However, this is never the case, as such a relationship depends on the cross-sectional shape and roughness of the floodplain, which not only varies along the river trajectory, but also changes due to natural phenomenon and human interventions. This introduces additional uncertainty into our assessment of whether the dikes are high enough.

Fortunately there is also extra conservatism built into this approach. For example, duration of high water plays a role: if discharge exceeds the capacity of the dike system, but only lasts for a short time (minutes or a couple hours), perhaps the dikes can withstand the overflow without eroding and causing flooding. This can be conceptualized by considering the joint probability of a high discharge and degradation of the dike leading to flooding:

where the conditional term represents the probability that the dike erodes (fails) given that the water depth exceeds the height. Assuming failure when the critical water depth is exceeded is conservative because it implies \(P(\text{flooding}|h_w>h_{dike})=1.0\), whereas in reality this is not the case, and the ‘true’ flooding probability is less than that computed in the equation above.

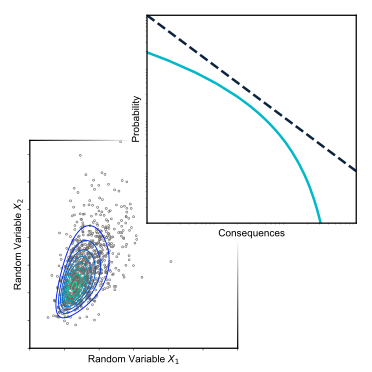

Later chapters of this book will introduce methods for taking these realities into account in the design and decision-making process. For now, we will see how our probabilistic design changes when more than one random variable must be considered.