Polarisation#

Polarisation States and Jones Vectors#

We have seen in Basic Electromagnetic and Wave Optics that light is an electromagnetic wave which satisfies Maxwell’s equations and the wave equation derived therefrom. Since the electric field is a vector which oscillates as function of time in a certain direction, we say that the wave has a certain polarisation. In this chapter we look at the different types of polarisation and how the polarisation of a light beam can be manipulated.

We start with Eqs. (61), (62) and (64) which show that the (real) electric field \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}(\mathbf{r},t)\) of a time-harmonic plane wave is always perpendicular to the direction of propagation, which is the direction of the wave vector \(\mathbf{k}\) as well as the direction of the Poynting vector (the direction of the power flow). Let the wave propagate in the \(z\)-direction:

Then the electric field vector does not have a \(z\)-component and hence the real electric field at \(z\) and at time \(t\) can be written as

where \({\cal A}_x\) and \({\cal A}_y\) are positive amplitudes and \(\varphi_x\), \(\varphi_y\) are the phases of the electric field components. While \(k\) and \(\omega\) are fixed, we can vary \({\cal A}_x\), \({\cal A}_y\), \(\varphi_x\) and \(\varphi_y\). This degree of freedom is why different states of polarisation exist: the state of polarisation is determined by the ratio of the amplitudes and by the phase difference \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x\) between the two orthogonal components of the light wave. Varying the quantity \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x\) means that we are ‘shifting’ \({\cal E}_y(\mathbf{r},t)\) with respect to \({\cal E}_x(\mathbf{r},t)\) [1]. Consider the electric field in a fixed plane \(z=0\):

The complex vector

is called the Jones vector. It is used to characterise the polarisation state. Let us see how, at a fixed position in space, the electric field vector behaves as a function of time for different choices of \({\cal A}_x\), \({\cal A}_y\) and \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x\).

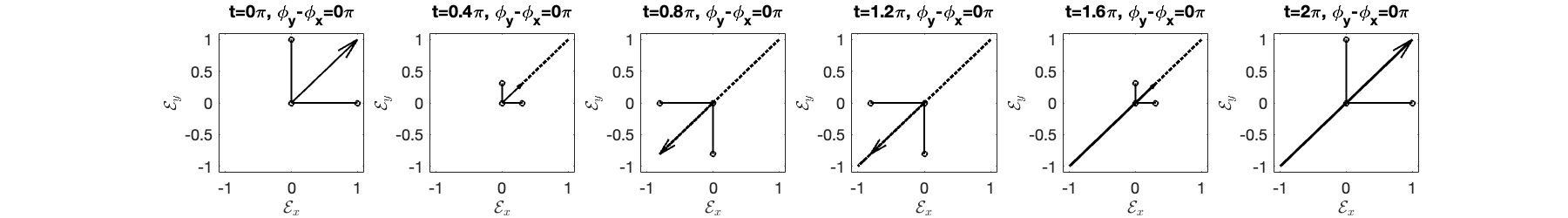

a) Linear polarisation: \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=0\) or \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=\pi\).] When \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=0\) we have

Equality of the phases: \(\varphi_y=\varphi_x\), means that the field components \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) and \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) are in phase: when \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) is large, \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) is large, and when \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) is small, \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) is small. We can write

which shows that for \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=0\) the electric field simply oscillates in one direction given by real the vector \({\cal A}_x \hat{\mathbf{x}} + {\cal A}_y \hat{\mathbf{y}}\). See Fig. 64.

If \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=\pi\) we have

In this case \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) and \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) are out of phase and the electric field oscillates in the direction given by the real vector \({\cal A}_x \hat{\mathbf{x}} - {\cal A}_y \hat{\mathbf{y}}\).

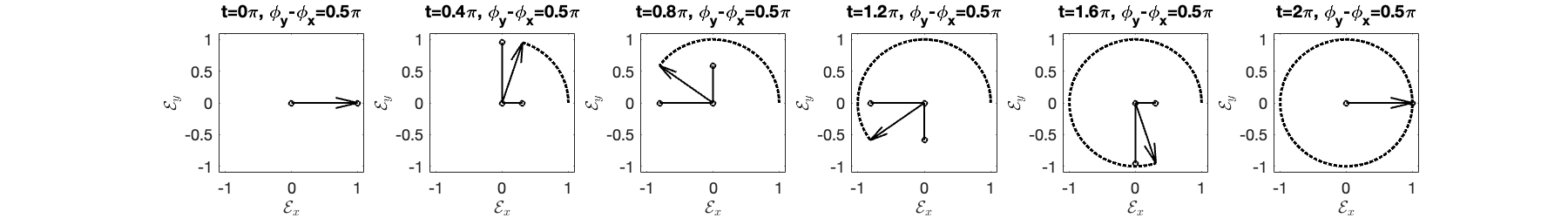

b) Circular polarisation: \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=\pm \pi/2\), \({\cal A}_x={\cal A}_y\). In this case the Jones vector is:

The field components \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) and \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) are \(\pi/2\) radian (90 degrees) out of phase: when \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) is large, \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) is small, and when \({\cal E}_x(z,t)\) is small, \({\cal E}_y(z,t)\) is large. We can write for \(z=0\) and with \(\varphi_x=0\):

At a given position, the electric field vector moves along a circle as time proceeds. When for an observer looking towards the source, the electric field is rotating anti-clockwise, the polarisation is called left-circularly polarised (+ sign in (268)), while if the electric vector moves clockwise, the polarisation is called right-circularly polarised (- sign in (268)).

c) Elliptical polarisation: \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=\pm \pi/2\), \({\cal A}_x\) and \({\cal A}_y\) arbitrary. The Jones vector is:

In this case we get instead of (268) (again taking \(\varphi_x=0\)):

which shows that the electric vector moves along an ellipse with major and minor axes parallel to the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axis. When the + sign applies, the field is called left-elliptically polarised, otherwise it is called right-elliptically polarised.

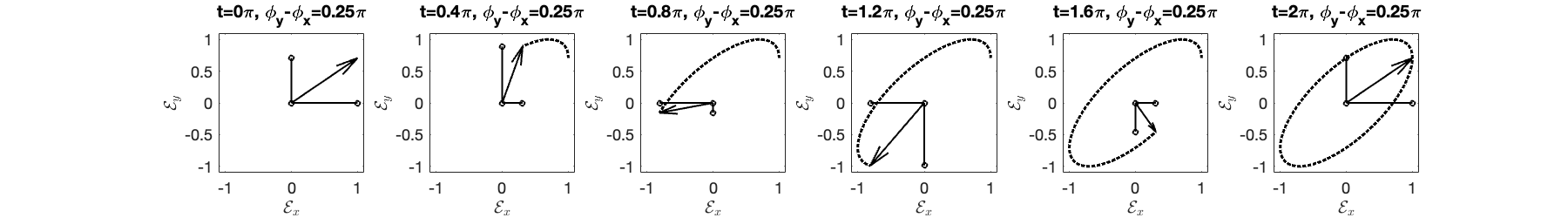

d) Elliptical polarisation: \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=\) anything else, \({\cal A}_x\) and \({\cal A}_y\) arbitrary. The Jones vector is now the most general one:

It can be shown that the electric field vector moves always along an ellipse. The exact shape and orientation of this ellipse varies with the difference in phase \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x\) and the ratio of the amplitude \({\cal A}_x,{\cal A}_y\) and, except when \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x = \pm \pi/2\), the major and minor axis of the ellipse are not parallel to the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axis. See Fig. 66.

Remarks.

Frequently the Jones vector is normalised such that

The normalized vector represents of course the same polarisation state as the unnormalised one. In general, multiplying the Jones vector by a complex number does not change the polarisation state. If we multiply for example by \(e^{i\theta}\), this has the same result as changing the instant that \(t=0\), hence it does not change the polarisation state. In fact:

We will show in Angular Spectrum Method that a general time-harmonic electromagnetic field, is a superposition of plane waves with wave vectors of the same length determined by the frequency of the wave but with different directions. An example is the electromagnetic field near the focal plane of a strongly converging lens. There is then no particular direction of propagation to which the electric field should be perpendicular. In other words, there is no obvious choice for a plane in which the electric field oscillates as function of time. It can nevertheless be shown that for every point in space such a plane exists, but the orientation of the plane varies in general with position. Furthermore, the electric field in a certain point moves along an ellipse in the corresponding plane, but the shape of the ellipse and the orientation of its major axis can be arbitrary. We can conclude that in any point of an arbitrary time-harmonic electromagnetic field, the electric (and in fact also the magnetic) field vector prescribes as function of time an ellipse in some plane which depends on position[2]. In this chapter we only consider the field and polarisation state of a single plane wave.

Fig. 64 Linear polarisation#

Fig. 65 Circular polarisation#

Fig. 66 Elliptical polarisation#

Illustration of different types of polarisation. The horizontal and vertical arrows indicate the momentary field components \({\cal E}_x, {\cal E}_y\). The thick arrow indicates the vector \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}\). The black curve indicates the trajectory of \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}(t)\).

External source

KhanAcademy - Polarization of light, linear and circular: Explanation of different polarisation states and their applications.

Creating and Manipulating Polarisation States#

We have seen how Maxwell’s equations allow the existence of plane waves with many different states of polarisation. But how can we create these states, and how do these states manifest themselves?

Natural light often does not have a definite polarisation. Instead, the polarisation fluctuates rapidly with time. To turn such randomly polarised light into linearly polarised light in a certain direction, we must extinguish the light polarised in the perpendicular direction.The remaining light is then linearly polarised along the desired direction. One could do this by using light reflected under the Brewster angle (which extinguishes p-polarised light), or one could let light pass through a dichroic crystal, which is a material which absorbs light polarised perpendicular to its so-called optic axis. A third method is sending the light through a wire grid polariser, which consists of a metallic grating with sub-wavelength slits. Such a grating only transmits the electric field component that is perpendicular to the slits.

So suppose that with one of these methods we have obtained linearly polarised light. Then the question rises how the state of linear polarisation can be changed into circularly or elliptically polarised light? Or how the state of linear polarisation can be rotated over a certain angle? We have seen that the polarisation state depends on the ratio of the amplitudes and on the phase difference \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x\) of the orthogonal components \({\cal E}_y\) and \({\cal E}_x\) of the electric field. Thus, to change linearly polarised light to some other state of polarisation, a certain phase shift (say \(\Delta \varphi_x\)) must be introduced to one component (say \({\cal E}_x\)), and another phase shift \(\Delta \varphi_y\) to the orthogonal component \({\cal E}_y\). We can achieve this with a birefringent crystal, such as calcite. What is special about such a crystal is that it has two refractive indices: light polarised in a certain direction experiences a refractive index \(n_o\), while light polarised perpendicular to it feels another refractive index \(n_e\) (the subscripts \(o\) and \(e\) stand for “ordinary” and “extraordinary”, but for our purpose we do not need to understand this terminology). The direction for which the refractive index is smallest (which can be either \(n_o\) or \(n_e\)) is called the fast axis because its phase velocity is largest, and the other direction is the slow axis. Because there are two different refractive indices, one can see double images through a birefringent crystal[3]. The difference between the two refractive indices \(\Delta n=n_e-n_o\) is called the birefringence.

Suppose \(n_e>n_o\) and that the fast axis, which corresponds to \(n_o\) is aligned with \({\cal E}_x\), while the slow axis (which then has refractive index \(n_e\)) is aligned with \({\cal E}_y\). If the wave travels a distance \(d\) through the crystal, \({\cal E}_y\) will accumulate a phase \(\Delta \varphi_y=\frac{2\pi n_e}{\lambda}d\), and \({\cal E}_x\) will accumulate a phase \(\Delta \varphi_x=\frac{2\pi n_o}{\lambda}d\). Thus, after propagation through the crystal the phase difference \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x\) has increased by

Jones Matrices#

By letting light pass through crystals of different thicknesses \(d\) we can create different phase differences between the orthogonal field components and in this way we can create different states of polarisation. To be specific, let \(\mathbf{J}\), as given by (264), be the Jones vector of the plane wave before the crystal. Then we have, for the Jones vector after the passage through the crystal:

where

A matrix such as \({\cal M}\), which transfers one state of polarisation of a plane wave in another, is called a Jones matrix. Depending on the phase difference which a wave accumulates by traveling through the crystal, these devices are called quarter-wave plates (phase difference \(\pi/2\)), half-wave plates (phase difference \(\pi\)), or full-wave plates (phase difference \(2\pi\)). The applications of these wave plates will be discussed in later sections.

Consider as example the Jones matrix which described the change of linear polarised light into circular polarisation. Assume that we have diagonally (linearly) polarised light, so that

We want to change it to circularly polarised light, for which

where one can check that indeed \(\varphi_y-\varphi_x=\pi/2\). This can be done by passing the light through a crystal such that \({\cal E}_y\) accumulates a phase difference of \(\pi/2\) with respect to \({\cal E}_x\). The transformation by which this is accomplished can be written as

The matrix on the left is the Jones matrix describing the operation of a quarter-wave plate.

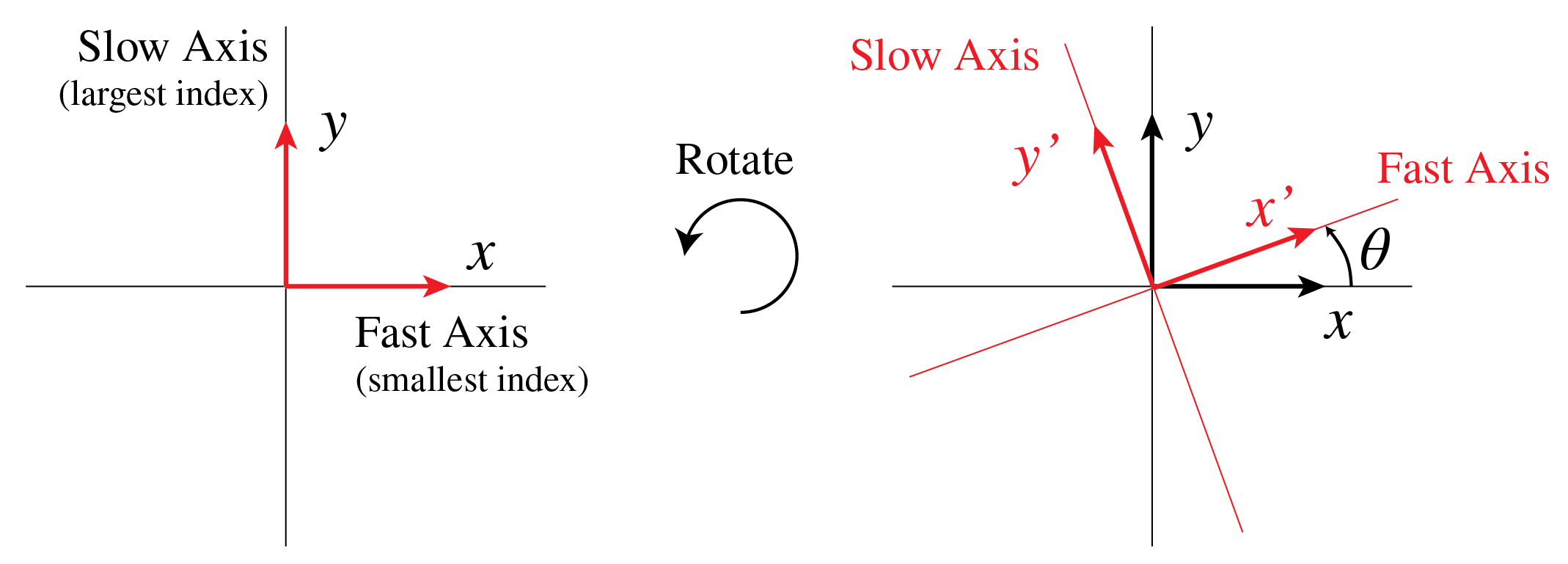

Another important Jones matrix is the rotation matrix. In the preceding discussion it was assumed that the fast and slow axes were aligned with the \(x\)- and \(y\)-direction (i.e. they were parallel to \({\cal E}_x\) and \({\cal E}_y\)). Suppose now that the slow and fast axes of the wave plate no longer coincide with \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}\) and \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}\), but rather with some other \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}'\) and \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}'\) as in Fig. 67. In that case we apply a basis transformation: the electric field vector which is expressed in the \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}\) basis should first be expressed in the \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}'\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}'\) basis before applying the Jones matrix of the wave plate to it. After applying the Jones matrix, the electric field has to be transformed back from the \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}'\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}'\) basis to the \( \widehat{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}\) basis.

Let \(\mathbf{E}\) be given in terms of its components on the \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) basis:

To find the components \(E_{x'}\), \(E_{y'}\) on the \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}'\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}'\) basis:

we first write the unit vectors \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}'\) and \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}'\) in terms of the basis \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) (see Fig. 67)

By substituting (278) and (279) into (277) we find

Comparing with (276) implies

where \({\cal R}_{\theta}\) is the rotation matrix over an angle \(\theta\) in the anti-clockwise direction: [4]

That \({\cal R}(\theta)\) indeed is a rotation over angle \(\theta\) in the anti-clockwise direction is easy to see by considering what happens when \({\cal R}_\theta\) is applied to the vector \((1,0)^T\). Since \({\cal R}_\theta^{-1}={\cal R}_{-\theta}\) we get:

This relationship expresses the components \(E_{x'}\), \(E_{y'}\) of the Jones vector on the \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}'\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}'\) basis, which is aligned with the fast and slow axes of the crystal, in terms of the components \(E_x\) and \(E_y\) on the original basis \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}\). If the matrix \({\cal M}\) describes the Jones matrix as defined in (275), then the matrix \(M_{\theta}\) for the same wave plate but with \(x'\) as slow and \(y'\) as fast axis, is, with respect to the \(\widehat{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\widehat{\mathbf{y}}\) basis, given by:

For more information on basis transformations, see Basis transformations.

Fig. 67 If the wave plate is rotated, the fast and slow axis no longer correspond to \(x\) and \(y\). Instead, we have to introduce a new coordinate system (\(x',y'\)).#

Linear Polarisers#

A polariser that only transmits horizontally polarised light is described by the Jones matrix:

Clearly, horizontally polarised light is completely transmitted, while vertically polarised light is not transmitted at all. More generally, for light that is polarised at an angle \(\alpha\), we get

The amplitude of the transmitted field is reduced by the factor \(\cos\alpha\), which implies that the intensity of the transmitted light is reduced by the factor \(\cos^2 \alpha\). This relation is known as Malus’ law.

Degree of Polarisation#

Natural light such as sun light is unpolarised. The instantaneous polarisation of unpolarised light fluctuates rapidly in a random manner. A linear polariser produces linear polarised light from unpolarised light. It follows from (286) that the intensity transmitted by a linear polariser when unpolarised light is incident, is the average value of \(\cos^2\alpha\) namely \(\frac{1}{2}\), times the incident intensity.

Light that is a mixture of polarised and unpolarised light is called partially polarised. The degree of polarisation is defined as the fraction of the total intensity that is polarised:

Quarter-Wave Plates#

A quarter-wave plate has already been introduced above. It introduces a phase shift of \(\pi/2\), so its Jones matrix is

because \(\exp(i\pi/2)=i\). To describe the actual transmission through the quarter-wave plate, the matrix should be multiplied by some global phase factor, but because we only care about the phase difference between the field components, this global phase factor can be omitted without problem. The quarter-wave plate is typically used to convert linearly polarised light to elliptically polarised light and vice-versa[5]. If the incident light is linearly polarised at angle \(\alpha\), the state of polarisation after the quarter-wave plate is

In particular, if incident light is linear polarised under \(45^o\), or equivalently, if the quarter wave plate is rotated over this angle, it will transform linearly polarised light into circularly polarised light (and vice versa).

A demonstration is shown in[6].

Half-Wave Plates#

A half-wave plate introduces a phase shift of \(\pi\), so its Jones matrix is

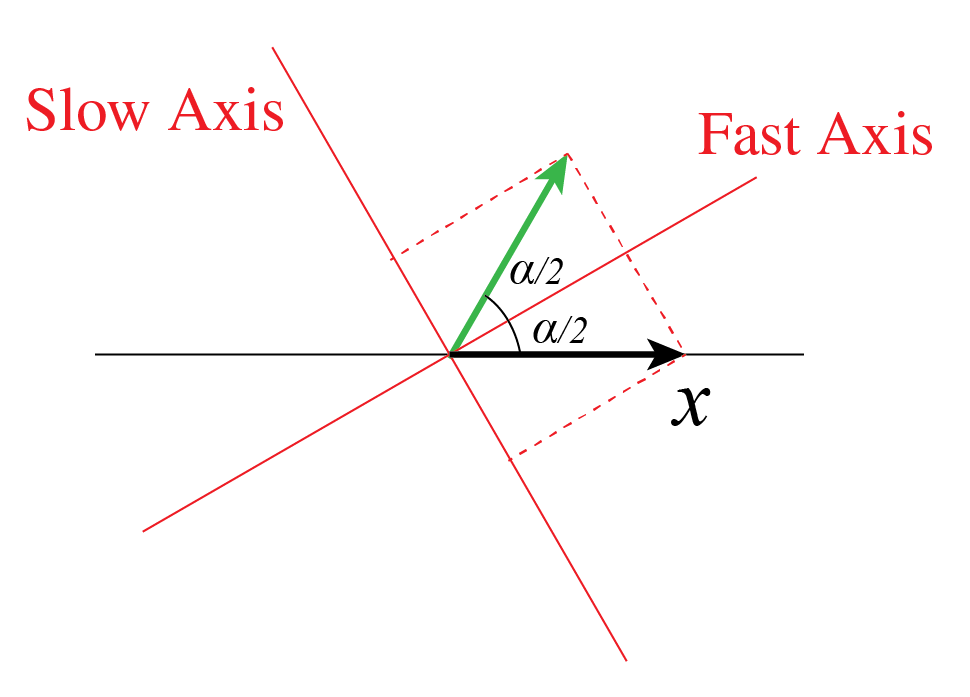

because \(\exp(i\pi)=-1\). An important application of the half-wave plate is to change the orientation of linearly polarised light. After all, what this matrix does is mirroring the polarisation state in the \(x\)-axis. Thus, if we choose our mirroring axis correctly (i.e. if we choose the orientation of the wave plate correctly), we can change the direction in which the light is linearly polarised arbitrarily[7][8]. To give an example: a wave with linear polarisation parallel to the \(x\)-direction, can be rotated over angle \(\alpha\) by rotating the crystal such that the fast axis makes angle \(\alpha/2\) with the \(x\)-axis. Upon propagation through the crystal, the slow axis gets an additional phase of \(\pi\), due to which the electric vector makes angle \(\alpha\) with the \(x\)-axis (see Fig. 68). It is not difficult to verify that when the fast and slow axis are interchanged, the same linear state of polarisation results.

Fig. 68 Rotation of horizontally polarised light over an angle \(\alpha\) using a half-wave plate.#

Full-Wave Plates#

A full-wave plate introduces a phase difference of \(2\pi\), which is the same as introducing no phase difference between the two field components. So what can possibly be an application for a full-wave plate? We recall from Eq. (273) that the phase difference is \(2\pi\) only for a particular wavelength. If we send through linearly (say vertically) polarised light of other wavelengths, these will become elliptically polarised, while the light with the correct wavelength \(\lambda_0\) will stay vertically polarised. If we then let all the light pass through a horizontal polariser, the light with wavelength \(\lambda_0\) will be completely extinguished, while the light of other wavelengths will be able to pass through at least partially. Therefore, full-wave plates can be used to filter out specific wavelengths of light.

More on Jones matrices#

If the direction of either the slow or fast axis is given and the ordinary and extra-ordinary refractive indices \(n_o\) and \(n_e\), it is easy to write down the Jones matrix of a birefringent plate of given thickness \(d\) using the rotation matrices, see (284). Instead of using the rotation matrices, one can also write down a system of equations for the elements of the Jones matrix. Suppose that \(\hat{\mathbf{v_o}}=v_{o,x}+\hat{\mathbf{x}}+v_{o,y}\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{v_e}}=v_{e,x}\hat{\mathbf{x}}+ v_{e,y} \hat{\mathbf{y}}\), are in the direction of the ordinary and the extra-ordinary axes, respectively. Then if the Jones matrix is

then

which implies

Similarly, for a linear polariser it is simple to write down the Jones matrix if one knows the direction in which the polariser absorbs or transmits all the light: use (285) in combination with the rotation matrices. Alternatively, if \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\) is in the direction of the linear polariser and \(\hat{\mathbf{w}}\) is perpendicular to it, we have

which is a system of equation of type (291) for the elements of the Jones matrix.

Suppose now that the complex (2,2)-matrix (290) is given. How can one verify whether this matrix corresponds to a linear polariser or to a wave plate? Note that the elements of a Jones matrix are in general complex.

1. Linear Polariser. The matrix corresponds to a linear polariser if there is a real vector which remains invariant under \({\cal M}\) and all vectors orthogonal to this vector are mapped to zero. In other words, there must be an orthogonal basis of real eigenvectors and one of the eigenvalues must be 1 and the other 0. Hence, to check that a given matrix corresponds to a linear polariser, one should verify that one eigenvalue is 1 and the other is 0 and furthermore that the eigenvectors are real orthogonal vectors. It is important to check that the eigenvectors are real because if they are not, they do not correspond to particular linear polarisation directions and then the matrix does not correspond to a linear polariser.

2. Wave plate. To show that the matrix corresponds to a wave plate, there should exist two real orthogonal eigenvectors with, in general, complex eigenvalues of modulus 1. In fact, one of the eigenvectors corresponds to the ordinary axis with refractive index \(n_{o}\), and the other to the extra-ordinary axis with refractive index \(n_e\). The eigenvalues are then

where \(d\) is the thickness of the plate and \(k\) is the wave number. Hence to verify that a \((2,2)\)-matrix corresponds to a wave plate, one has to compute the eigenvalues and check that these have modulus 1 and that the corresponding eigenvectors are real vectors and orthogonal.

3. Jones matrix for propagation through sugars In sugars, left and right circular-polarised light propagate with their own refractive index. Therefore sugars are called circular birefringent. The matrix (290) corresponds to propagation through sugar when there are two real orthogonal unit vectors \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{w}}\) such that the circular polarisation states

are eigenstates of \({\cal M}\) with complex eigenvalues with modulus 1.

Decomposition of an Elliptical Polarisation state into sums of Linear & of Circular States#

Any elliptical polarisation state can be written as the sum of two perpendicular linear polarised states:

Furthermore, any elliptical polarisation state can be written as the sum of two circular polarisation states, one right- and the other left-circular polarised:

We conclude that to study what happens to elliptic polarisation, it suffices to consider two orthogonal linear polarisations, or, if that is more convenient, left- and right-circular polarised light. In a birefringent material each of two linear polarisations, namely parallel to the o-axis and parallel to the e-axis, propagate with their own refractive index. To predict what happens to an arbitrary linear polarisation state which is not aligned to either of these axes, or more generally what happens to an elliptical polarisation state, we write this polarisation state as a linear combination of o- and e-states, i.e. we expand the field on the o- and e-basis.

To see what happens to an arbitrary elliptical polarisation state in a circular birefringent material, the incident light is best written as linear combination of left-and right-circular polarisations.

External sources in recommended order

Double Vision - Sixty Symbols: Demonstration of double refraction by a calcite crystal due to birefringence.

MIT OCW - Linear Polarizer: Demonstration of linear polarizers and linear polarisation.

MIT OCW - Polarization Rotation Using Polarizers: Demonstration of polarisation rotation using linear polarisers.

Demonstration of a QuarterWavePlate by Andrew Berger.

MIT OCW - Quarter-wave Plate: Demonstration of the quarter-wave plate to create elliptical (in particular circular) polarisation.

Demonstration of a HalfWavePlate by Andrew Berger.

MIT OCW - Half-wave Plate: Demonstration of the half-wave plate.