Geometrical Optics#

Nice software for practicing geometrical optics:

https://www.geogebra.org/m/X8RuneVy

Introduction#

Geometrical optics is an old subject but it is still essential to understand and design optical instruments such as camera’s, microscopes, telescopes etc. Geometrical optics started long before light was described as a wave as is done in wave optics, and long before it was discovered that light is an electromagnetic wave and that optics is part of electromagnetism.

In this chapter we go back in history and treat geometrical optics. That may seem strange now that we have a much more accurate and better theory at our disposal. However, the predictions of geometrical optics are under quite common circumstances very useful and also very accurate. In fact, for many optical systems and practical instruments there is no alternative for geometrical optics because more accurate theories are much too complicated to use.

When a material is illuminated, its molecules start to radiate spherical waves (more precisely, they radiate like tiny electric dipoles) and the total wave scattered by the material is the sum of all these spherical waves. A time-harmonic wave has at every point in space and at every instant of time a well defined phase. A wave front is a set of space-time points where the phase has the same value. At any fixed time, the wave front is called a surface of constant phase. This surface moves with the phase velocity in the direction of its local normal.

For plane waves we have shown in the previous chapter that the surfaces of constant phase are planes and that the normal to these surfaces is in the direction of the wave vector which coincides with the direction of the phase velocity as well as with the direction of the flow of energy (the direction of the Poynting vector). For general waves, the local direction of energy flow is given by the direction of the Poynting vector. Provided that the radius of curvature of the surfaces is much larger than the wavelength, the normal to the surfaces of constant phase may still be considered to be in the direction of the local flow of energy. Such waves behave locally as plane waves and their effect can be accurately described by the methods of geometrical optics.

Geometrical optics is based on the intuitive idea that light consists of a bundle of rays. But what is a ray?

Note

A ray is an oriented curve which is everywhere perpendicular to the surfaces of constant phase and points in the direction of the flow of energy.

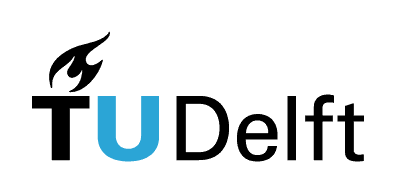

Consider a point source at some distance before an opaque screen with an aperture. According to the ray picture, the light distribution on a second screen further away from the source and parallel to the first screen is simply an enlarged copy of the aperture (see Fig. 14). The copy is enlarged due to the fanning out of the rays. However, this description is only accurate when the wavelength of the light is very small compared to the diameter of the aperture. If the aperture is only ten times the wavelength, the pattern is much broader due to the bending of the rays around the edge of the aperture. This phenomenon is called diffraction. Diffraction can not be explained by geometrical optics and will be studied in Scalar Diffraction Optics.

Fig. 14 Light distribution on a screen due to a rectangular aperture. Left: for a large aperture, we get an enlarged copy of the aperture. Right: for an aperture that is of the order of the wavelength there is strong bending (diffraction) of the light.#

Geometrical optics is accurate when the sizes of the objects in the system are large compared to the wavelength. It is possible to derive geometrical optics from Maxwell’s equations by formally expanding the electromagnetic field in a power series in the wavelength and retaining only the first term of this expansion [1]. However, this derivation is not rigorous because the power series generally does not converge (it is a so-called asymptotic series).

Although it is possible to incorporate polarisation into geometrical optics [2], this is not standard theory and we will not consider polarisation effects in this chapter

Principle of Fermat#

The starting point of the treatment of geometrical optics is the

Note

Principle of Fermat (1657). The path followed by a light ray between two points is the one that takes the least amount of time.

The speed of light in a material with refractive index \(n\), is \(c/n\), where \(c=3\times 10^8\) m/s is the speed of light in vacuum. At the time of Fermat, the conviction was that the speed of light must be finite, but nobody could suspect how incredibly large it actually is. In 1676 the Danish astronomer Ole Römer computed the speed from inspecting the eclipses of a moon of Jupiter and arrived at an estimate that was only 30% too low.

Let \(\mathbf{r}(s)\), be a ray with \(s\) the length parameter. The ray links two points \(S\) and \(P\). Suppose that the refractive index varies with position: \(n(\mathbf{r})\). Over the infinitesimal distance from \(s\) to \(s+\mathrm{d}s\), the speed of the light is

Hence the time it takes for light to go from \(\mathbf{r}(s)\) to \(\mathbf{r}(s+\mathrm{d}s)\) is:

and the total total time to go from \(S\) to \(P\) is:

where \(s_P\) is the distance along the ray from S to P. The optical path length [m] of the ray between S and P is defined by:

So the OPL is the distance weighted by the refractive index.

Note

Fermat’s principle is thus equivalent to the statement that a ray follows the path with shortest OPL.

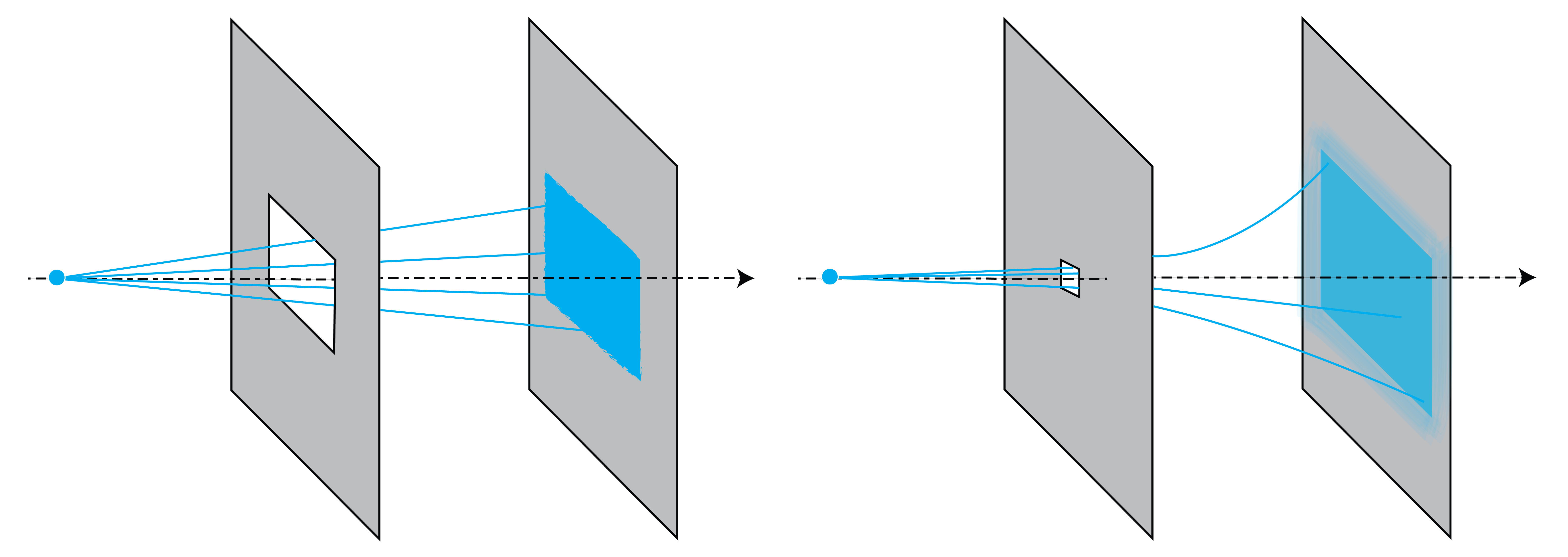

Fig. 15 Because the temperature close to the ground is higher, the refractive index is lower there. Therefore the rays bend upwards, creating a mirror image of the tree below the ground. (From Popular Science Monthly Volume 5, Public Domain, link).#

Remark. Actually, Fermat’s principle as formulated above is not complete. There are circumstances that a ray can take two paths between two points that have different travel times. Each of these paths then corresponds to a minimum travel time compared to nearby paths, so the travel time is in general a local minimum. An example is the reflection by a mirror discussed in the following section.

Some Consequences of Fermat’s Principle#

Homogeneous matter

In homogenous matter, the refractive index is constant and therefore paths of shortest OPL are straight lines. Hence in homogeneous matter rays are straight lines.

Inhomogeneous matter

When the refractive index is a function of position such as air with a temperature gradient, the rays bend towards regions of higher refractive index. In the case of Fig. 15 for example, the ray from the top of the tree to the eye of the observer passes on a warm day close to the ground because there the temperature is higher and hence the refractive index is smaller. Although the curved path is longer than the straight path, the total travel time of the light is less because near the ground the light speed is higher (since the refractive index is smaller). The observer gets the impression that the tree is upside down under the ground.

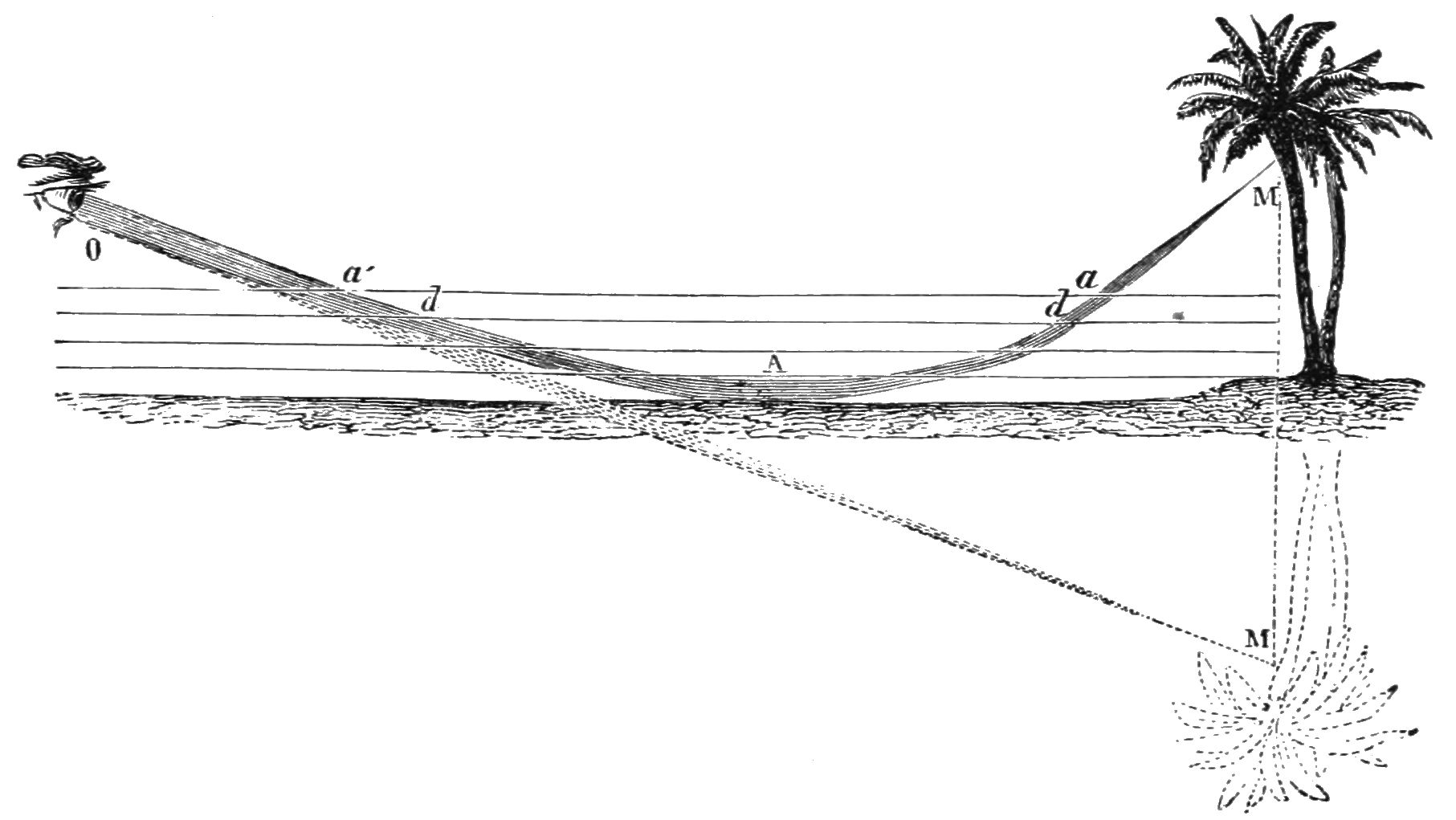

Law of reflection

Consider the mirror shown in Fig. 16. Since the medium above th mirror is homogeneous, a ray from point \(P\) can end up in \(Q\) in two ways: by going along a straight line directly form \(P\) to \(Q\) or alternatively by straight lines via the mirror. Both possibilities have different path lengths and hence different travel times and hence both are local minima mentioned at the end of the previous section. We consider here the path by means of reflection by the mirror. Let the \(x\)-axis be the intersection of the mirror and the plane through the points \(P\) and \(Q\) and perpendicular to the mirror. Let the \(y\)-axis be normal to the mirror. Let \((x_P, y_P)\) and \((x_Q,y_Q)\) be the coordinates of \(P\) and \(Q\), respectively. If \((x,0)\) is the point where a ray from \(P\) to \(Q\) hits the mirror, the travel time of that ray is

where \(n\) is the refractive index of the medium in \(y>0\). According to Fermat’s Principle, the point \((x,0)\) should be such that the travel time is minimum, i.e.

Hence

or

where \(\theta_i\) and \(\theta_r\) are the angles of incidence and reflection as shown in Fig. 16.

Fig. 16 Ray from \(P\) to \(Q\) via the mirror.#

Snell’s law of refraction

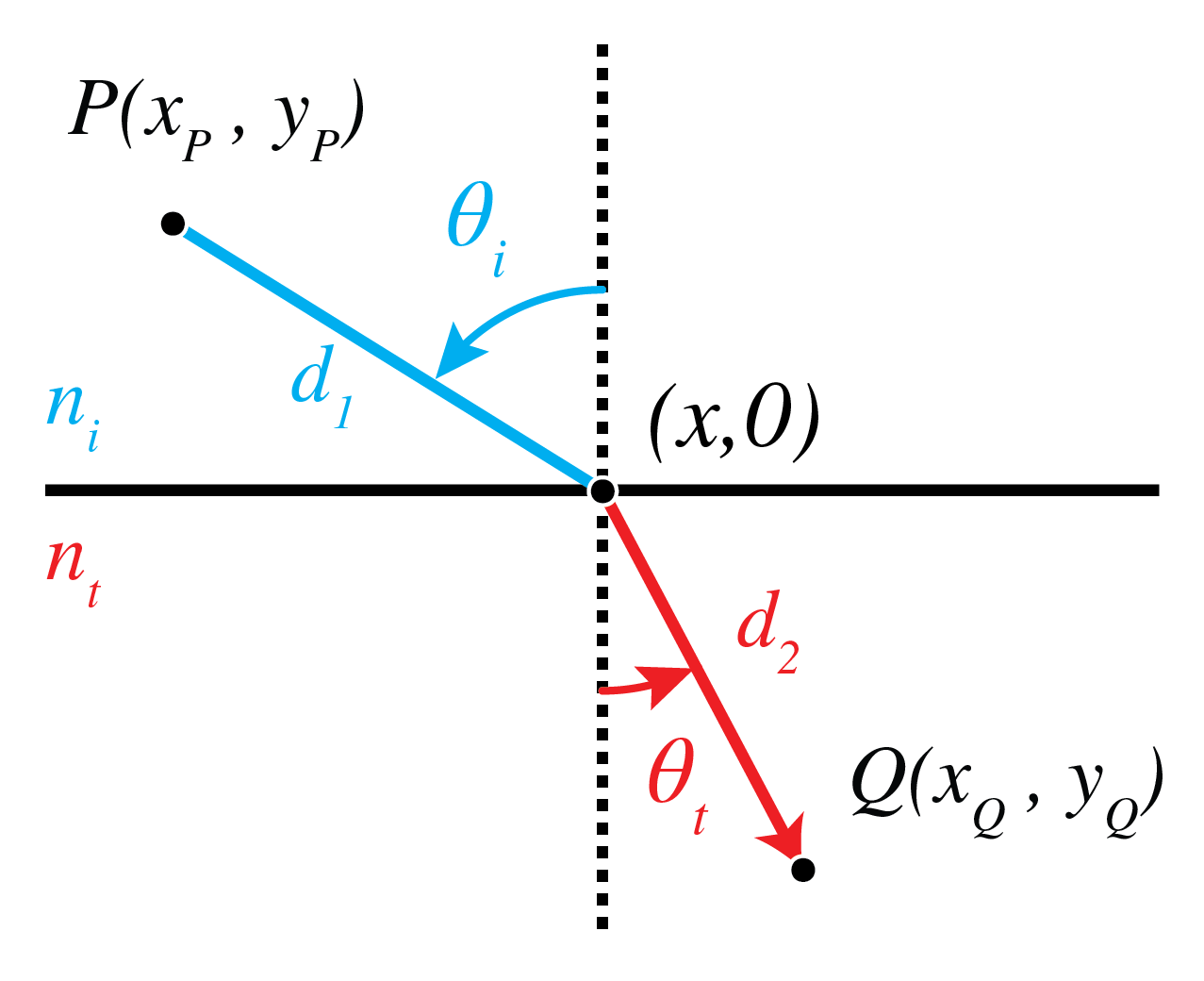

Next we consider refraction at an interface. Let \(y=0\) be the interface between a medium with refractive index \(n_i\) in \(y>0\) and a medium with refractive index \(n_t\) in \(y<0\). We use the same coordinate system as in the case of reflection above. Let \((x_P,y_P)\) and \((x_Q,y_Q)\) with \(y_P>0\) and \(y_Q<0\) be the coordinates of two points \(P\) and \(Q\) are shown in Fig. 17. What path will a ray follow that goes from \(P\) to \(Q\)? Since the refractive index is constant in both half spaces, the ray is a straight line in both media. Let \((x,0)\) be the coordinate of the intersection point of the ray with the interface. Then the travel time is

The travel time must be minimum, hence there must hold

where the travel time has been multiplied by the speed of light in vacuum. Eq. (168) implies

where \(\theta_i\) and \(\theta_t\) are the angles between the ray and the normal to the surface in the upper half space and the lower half space, respectively (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17 Ray from \(P\) to \(Q\) refracted by an interface.#

Hence we have derived the law of reflection and Snell’s law from Fermat’s principle. In Basic Electromagnetic and Wave Optics the reflection law and Snell’s law have been derived by a different method, namely from the continuity of the tangential electromagnetic field components at the interface.

Perfect Imaging by Conic Sections#

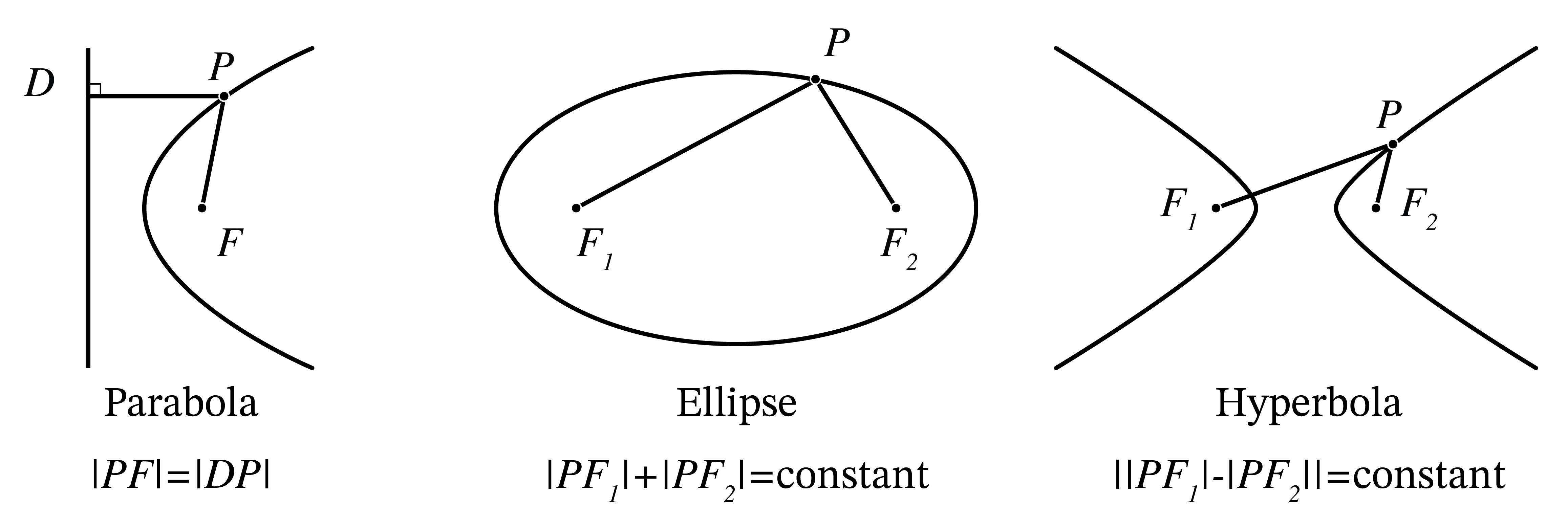

In this section the conic sections ellipse, hyperbole and parabola are important. In Fig. 18 their definitions are shown as a quick reminder[3].

Fig. 18 Overview of conic sections. The lower figure shows a definition that unifies the three definitions in the figure above by introducing a parameter called the eccentricity \(e\). The point \(F\) is the focus and the line \(e=\infty\) is the directrix of the conic sections.#

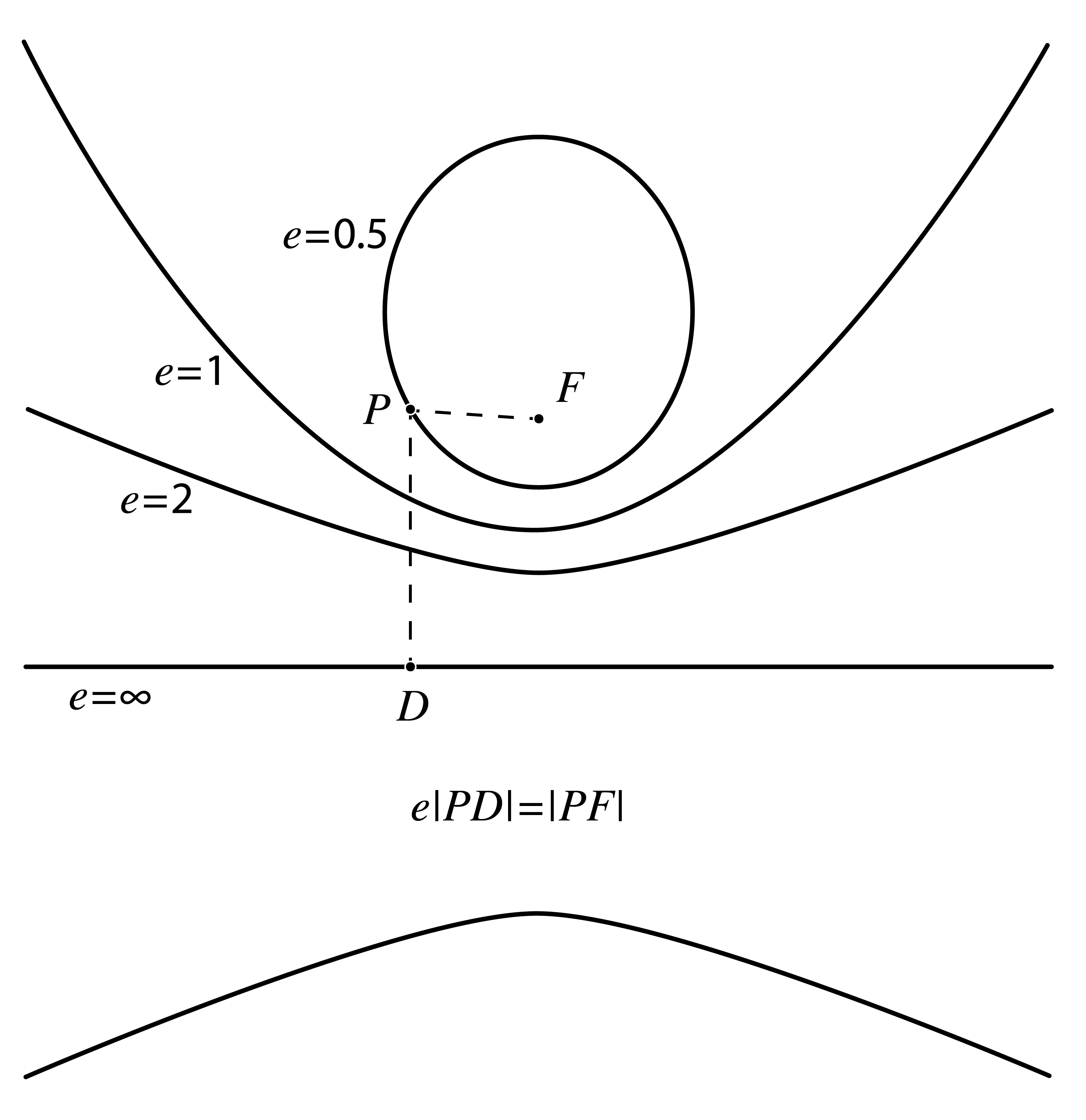

We start with explaining what in geometrical optics is meant by perfect imaging. Let \(S\) be a point source. The rays perpendicular to the spherical wave fronts emitted by \(S\) radially fan out from \(S\). Due to objects such as lenses etc. the spherical wave fronts are deformed and the direction of the ray are made to deviate from the radial propagation direction. When there is a point \(P\) and a cone of rays coming from point \(S\) and all rays in that cone intersect in point \(P\), then by Fermat’s principle, all these rays have traversed paths of minimum travel time. In particular, their travel times are equal and therefore they all add up in phase when they arrive in \(P\). Hence at \(P\) there is a high light intensity. Hence, if there is a cone of rays from point \(S\) which all intersect in a point \(P\) as shown in Fig. 19, point \(P\) is called the perfect image of \(S\). By reversing the direction of the rays, \(S\) is similarly a perfect image of \(P\). The optical system in which this happens is called stigmatic for the two points \(S\) and \(P\).

Fig. 19 Perfect imaging: a cone of rays which diverge from \(S\) and all intersect in point \(P\). The rays continue after \(P\).#

Remark. The concept of a perfect image point exists only in geometrical optics. In reality finite apertures of lenses and other imaging systems cause diffraction due to which image points are never perfect but blurred.

We summarise the main examples of stigmatic systems.

1. Perfect focusing and imaging by refraction. A parallel bundle of rays propagating in a medium with refractive index \(n_2\) can be focused into a point \(F\) in a medium \(n_1\). If \(n_2>n_1\), the interface between the media should be a hyperbole with focus \(F\), whereas if \(n_2<n_1\) the interface should be an ellipse with focus \(F\) (see Fig. 40 and Fig. 41). By reversing the rays we obtain perfect collimation. Therefore, a point \(S\) in air can be perfectly imaged onto a point \(F\) in air by inserting a piece of glass in between them with hyperbolic surfaces as shown in Fig. 41. These properties are derived in Problem 2.2.

2. Perfect focusing of parallel rays by a mirror. A bundle of parallel rays in air can be focused into a point \(F\) by a mirror of parabolic shape with \(F\) as focus (see Fig. 42). This is derived in Problem 2.3. By reversing the arrows, we get (within geometrical optics) a perfectly parallel beam. Parabolic mirrors are used everywhere, from automobile headlights to radio telescopes.

Remark.

Although we found that conic surfaces give perfect imaging for a certain pair of points, other points do not have perfect images in the sense that for a certain cone of rays, all rays are refracted (or reflected) to the same point.

External sources in recommended order

KhanAcademy - Geometrical Optics: Playlist on elementary geometrical optics.

Yale Courses - 16. Ray or Geometrical Optics I - Lecture by Ramamurti Shankar

Yale Courses - 17. Ray or Geometrical Optics II - Lecture by Ramamurti Shankar

Gaussian Geometrical Optics#

We have seen that, although by using lenses or mirrors which have surfaces that are conic sections we can perfectly image a certain pair of points, for other points the image is not perfect. The imperfections are caused by rays that make larger angles with the optical axis, i.e. with the symmetry axis of the system. Rays for which these angles are small are called paraxial rays. Because for paraxial rays the angles of incidence and transmission at the surfaces of the lenses are small, the sine of the angles in Snell’s Law are replaced by the angles themselves:

This approximation greatly simplifies the calculations. When only paraxial rays are considered, one may replace any surface by a sphere with the same curvature at its vertex. Errors caused by replacing a surface by a sphere are of second order in the angles the ray makes with the optical axis and hence are insignificant for paraxial rays. Spherical surfaces are not only more simple in the derivations but they are also much easier to manufacture. Hence in the optical industry spherical surfaces are used a lot. To reduce imaging errors caused by non-paraxial rays one applies two strategies: 1. adding more spherical surfaces; 2 replacing one of the spherical surfaces (typically the last before image space) by a non-sphere.

Note

In Gaussian geometrical optics only paraxial rays and spherical surfaces are considered. In Gaussian geometrical optics every point has a perfect image.

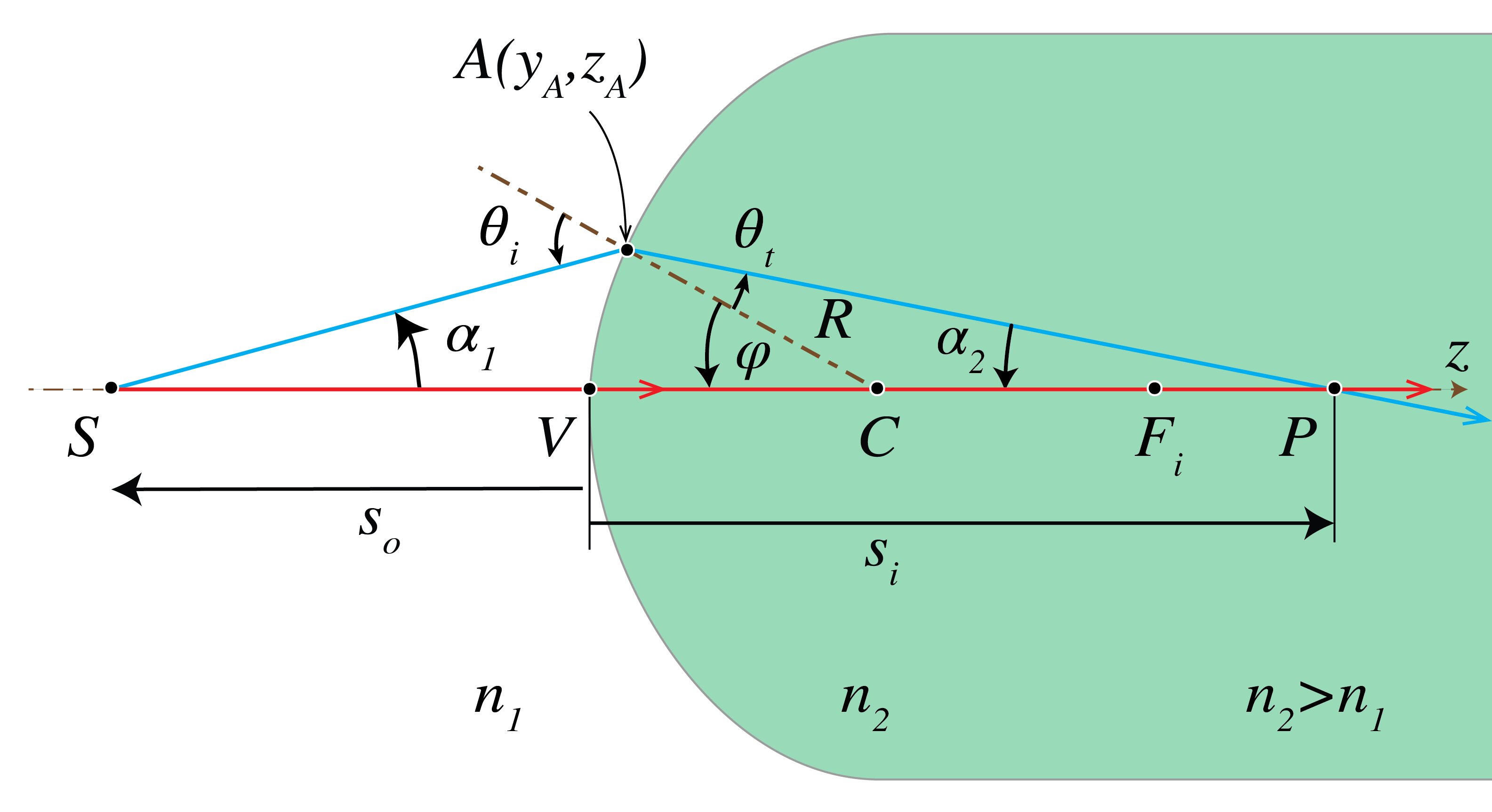

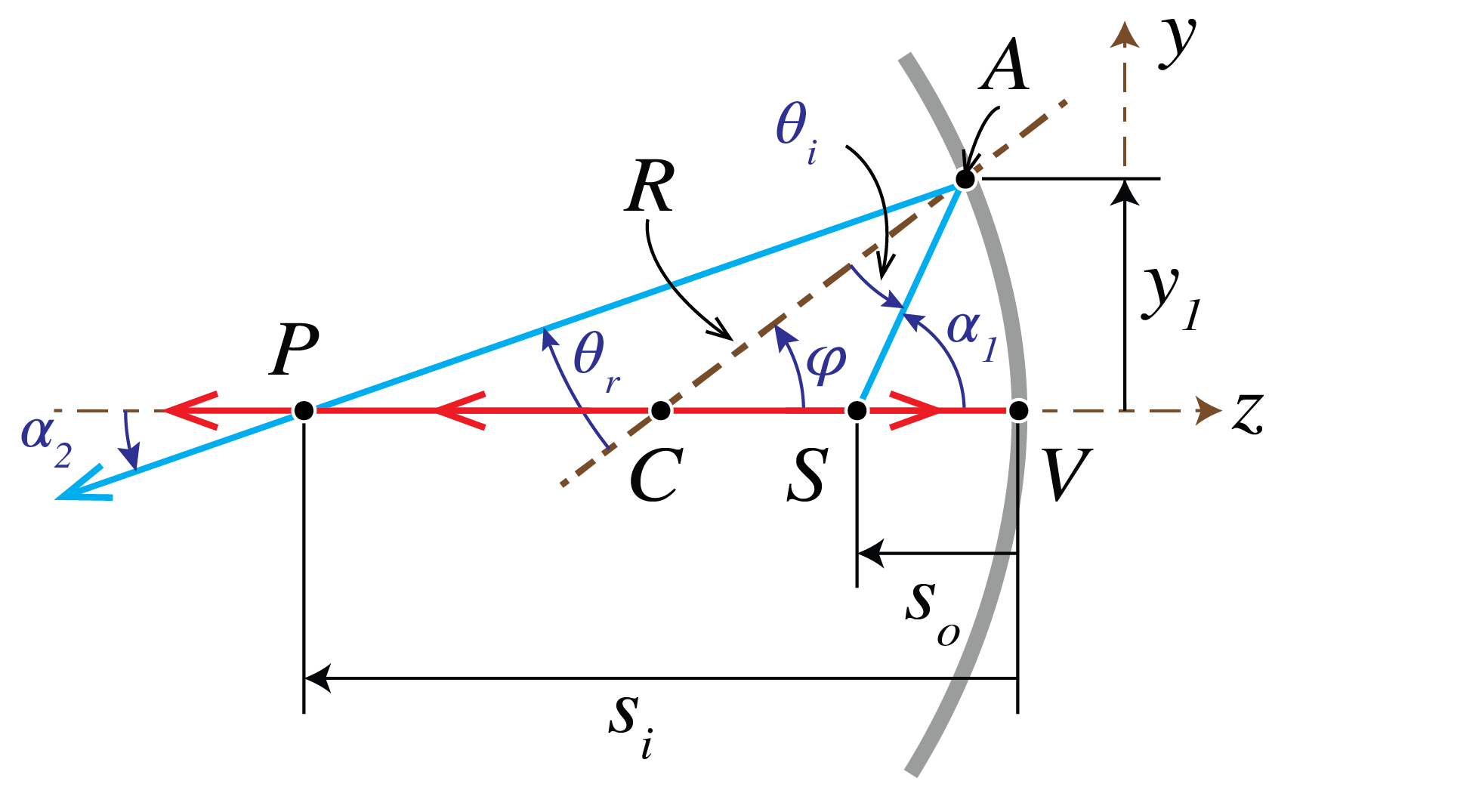

Gaussian Imaging by a Single Spherical Surface#

We will first show that within Gaussian optics a single spherical surface between two media with refractive indices \(n_1< n_2\) images all points perfectly (Fig. 20). The sphere has radius \(R\) and centre \(C\) which is inside medium 2. We consider a point object \(S\) to the left of the surface. We draw a ray from \(S\) perpendicular to the surface. The point of intersection is \(V\). Since for this ray the angle of incidence with the local normal on the surface vanishes, the ray continues into the second medium without refraction and passes through the centre \(C\) of the sphere. Next we draw a ray that hits the spherical surface in some point \(A\) and draw the refracted ray in medium 2 using Snell’s law in the paraxial form (170). Note that the angles of incidence and transmission must be measured with respect to the local normal at \(A\), i.e. with respect to \(CA\). We assume that this ray intersects the first ray in point \(P\). We will show that within the approximation of Gaussian geometrical optics, all rays from \(S\) pass through \(P\). Furthermore, with respect to a coordinate system \((y,z)\) with origin at \(V\), the \(z\)-axis pointing from \(V\) to \(C\) and the \(y\)-axis positive upwards as shown in Fig. 20, we have:

where

is called the power of the surface and where \(s_o\) and \(s_i\) are the \(z\)-coordinates of \(S\) and \(P\), respectively, hence \(s_0<0\) and \(s_i>0\) in Fig. 20.

Fig. 20 Imaging by a spherical interface between two media with refractive indices \(n_2>n_1\).#

Proof.

(Note: the proof is not part of the exam). It suffices to show that \(P\) is independent of the ray, i.e. of \(A\). We will do this by expressing \(s_i\) into \(s_o\) and showing that the result is independent of \(A\). Let \(\alpha_1\) and \(\alpha_2\) be the angles of the rays \(SA\) and \(AP\) with the \(z\)-axis as shown in Fig. 20. Let \(\theta_i\) be the angle of incidence of ray \(SA\) with the local normal \(CA\) on the surface and \(\theta_t\) be the angle of refraction. By considering the angles in triangle \(\Delta \text{SCA}\) we find

Similarly, from \(\Delta \,\text{CPA}\) we find

By substitution into the paraxial version of Snell’s Law (170), we obtain

Let \(y_A\) and \(z_A\) be the coordinates of point \(A\). Since \(s_o<0\) and \(s_i>0\) we have

Furthermore,

which is small for paraxial rays. Hence,

because it is second order in \(y_A\) and therefore is neglected in the paraxial approximation. Then, (176) becomes

By substituting (179) and (177) into (175) we find

or

which is (171). It implies that \(s_i\), and hence \(P\), is independent of \(y_A\), i.e. of the ray chosen. Therefore, \(P\) is a perfect image within the approximation of Gaussian geometrical optics.

When \(s_o \rightarrow -\infty\), the incident rays are parallel to the \(z\)-axis in medium 1 and the corresponding image point \(F_i\) is called the second focal point or image focal point. Its \(z\)-coordinate is given by:

and its absolute value (it is negative when \(n_2<n_1\)) is called the second focal length or image focal length.

When \(s_i\rightarrow \infty\), the rays after refraction are parallel to the \(z\)-axis and we get \(s_o \rightarrow -n_1 R/(n_2-n_1)\). The object point for which the rays in the medium 2 are parallel to the \(z\)-axis is called the first focal point or object focal point \(F_o\). Its \(z\)-coordinate is:

The absolute value \(|f_o|\) of \(f_o\) is called the front focal length or object focal length.

With (180) and (181), (171) can be rewritten as:

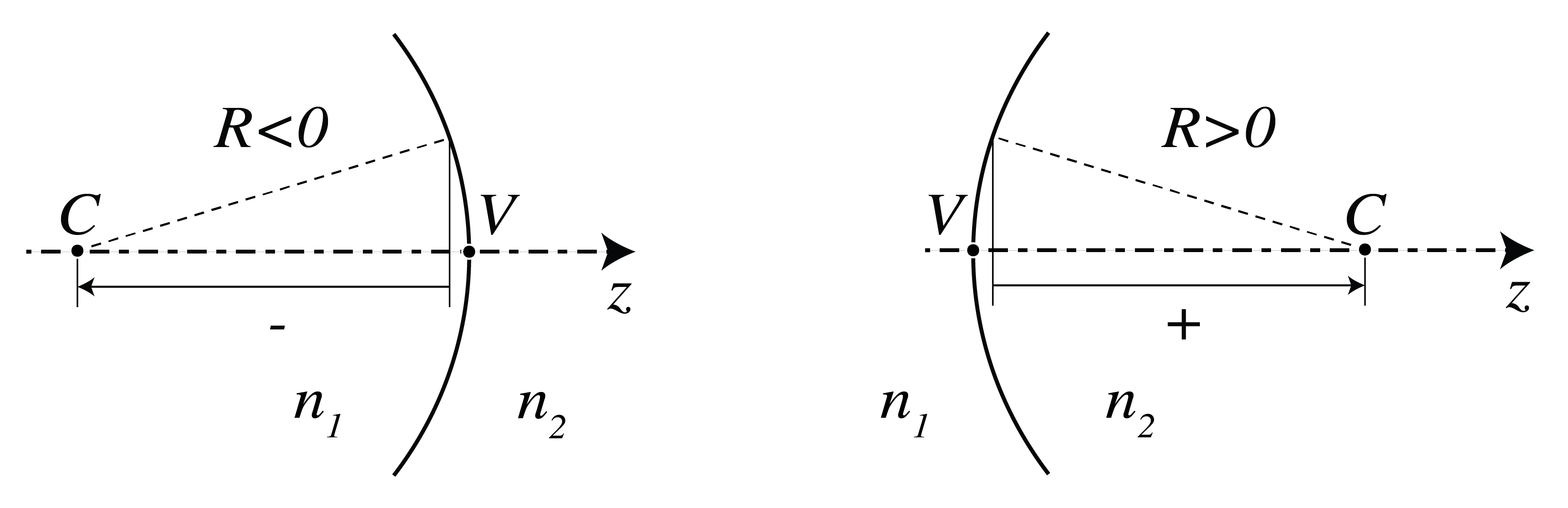

Virtual Images and Virtual Objects of a Single Spherical Surface#

If we adopt the sign convention listed in Table 2 below, it turns out that (171) holds generally. So far we have considered a convex surface of which the centre \(C\) is to the right of the surface, but (171) applies also to a concave surface of which the centre is to the left of the surface, provided that the radius \(R\) is chosen negative. The convention for the sign of the radius is illustrated in Fig. 21.

Fig. 21 Sign convention for the radius \(R\) of a spherical surface#

If the power \({\cal P}\) given by (172) is positive, then the surface makes bundles of incident rays convergent or less divergent. If the power is negative, incident bundles are made divergent or less convergent. The power of the surface can be negative because of two reasons:

\(R\)>0 and \(n_1>n_2\), or

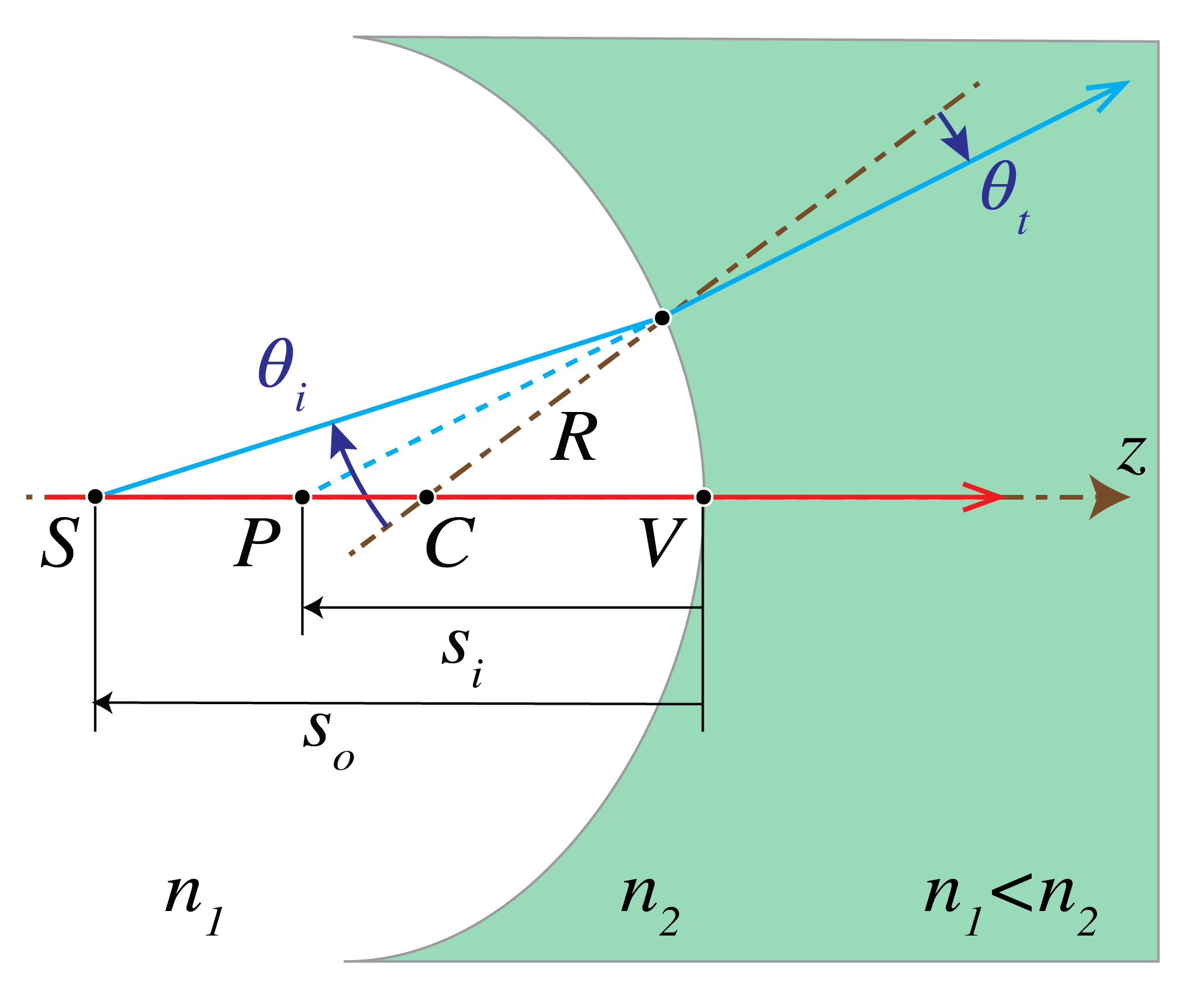

\(R\)<0 and \(n_1<n_2\), but the effect of the two cases is the same. For any object to the left of the surface: \(s_o<0\), (182) and a negative power imply that \(s_i<0\), which suggests that the image is to the left of the surface. Indeed, in both Figs. the diverging ray bundle emitted by S is made more strongly divergent by the surface. By extending these rays in image space back to object space (without refraction at the surface), they are seen to intersect in a point \(P\) to the left of the surface. This implies that for an observer at the right of the surface it looks as if the diverging rays in image space are emitted by \(P\). Because there is no actual concentration of light intensity at \(P\), it is called a virtual image, in contrast with the real images that occur to the right of the surface and where there is an actual concentration of light energy. We have in this case \(f_o>0\) and \(f_<0\), which means that the object and image focal points are to the right and left, respectively, of the surface.

Note that also when the power is positive, a virtual image can occur, namely when the object \(S\) is in between the object focal point \(F_o\) and the surface. Then the bundle of rays from S is so strongly diverging that the surface can not convert it into a convergent bundle and hence again the rays in image space seem to come from a point \(P\) to the left of the surface. This agrees with the fact that when \({\cal P}>0\) and \(f_o< s_o<0\), (182) implies that \(s_i<0\).

Fig. 22 Imaging by a concave surface (\(R<0\)) with \(n_2>n_1\). All image points are to the left of the surface, i.e. are virtual (\(s_i<0\)).#

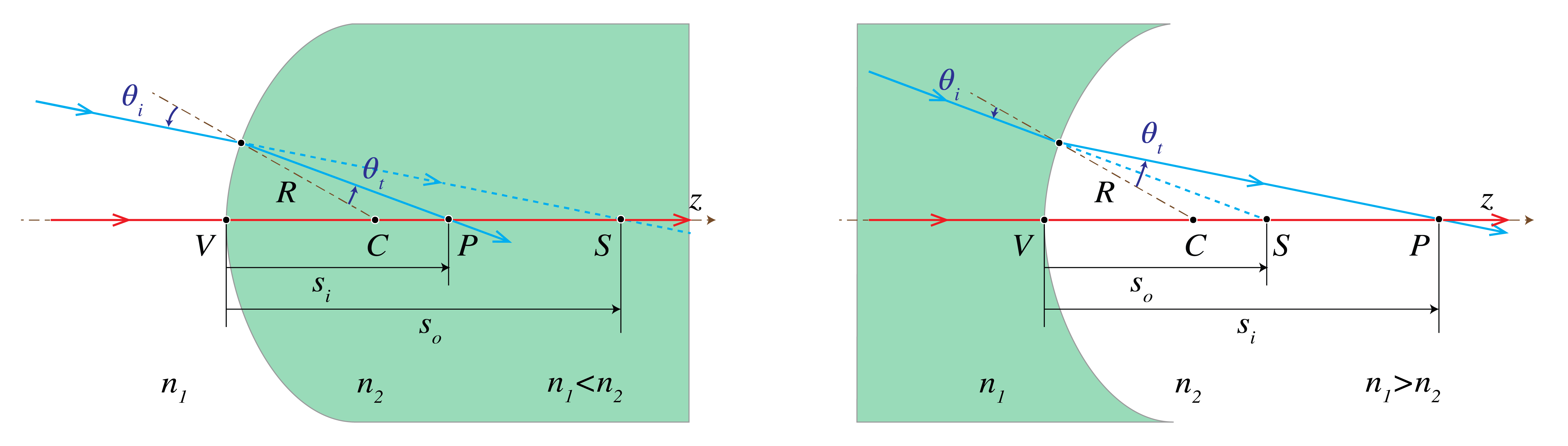

Finally we look at a case that there is a bundle of convergent rays incident from the left on the surface which when extended into the right medium without refraction at the surface, would intersect in a point \(S\). Since this point is not actually present, it is called a virtual object point, in contrast to real object points which are to the left of the surface. The coordinate of a virtual object point is positive: \(s_o>0\). One may wonder why we look at this case. The reason is that if we have several spherical surfaces behind each other, we can compute the image of an object point by first determining the intermediate image by the most left surface and then use this intermediate image as object for the next surface and so on. In such a case it can easily happen that an intermediate image is to the right of the next surface and hence is a virtual object for that surface. In the case of Fig. 23 at the left, the power is positive, hence the convergent bundle of incident rays is made even more convergent which leads to a real image point. Indeed when \(s_o>0\) and \({\cal P}>0\) then (171) implies that always \(s_i>0\). At the right of Fig. 23 the power is negative but is not sufficiently strong to turn the convergent incident bundle into a divergent bundle. So the image is still real. However, the image will be virtual when the virtual object \(S\) is to the right of \(F_o\) (which in this case is to the right of the surface) since then the bundle of rays converges so weakly that the surface turns is into a divergent bundle.

Fig. 23 Imaging of a virtual object \(S\) by a spherical interface with \(R>0\) between two media with refractive indices \(n_1>n_2\) (left) and \(n_2>n_1\) (right).#

In conclusion: provided the sign convention listed in Table 2 is used, formula (171) can always be used to determine the image of a given object by a spherical surface.

quantity |

positive |

negative |

|---|---|---|

\(s_o\), \(s_i\). \(f_0\), \(f_i\) |

corresponding point is to the right of vertex |

corresponding point is to left of vertex |

\(y_o\), \(y_i\) |

object, image point above optical axis |

object, image point below optical axis |

\(R\) |

centre of curvature right of vertex |

centre of curvature left of vertex |

Refractive index \(n\) ambient medium of a mirror |

before reflection |

after reflection |

Ray Vectors and Ray Matrices#

Now that we know that within Gaussian geometrical optics a single spherical surface images every object point to a perfect, real or virtual, image point it is easy to see that any row of spherical surfaces separated by homogeneous materials will also image any point perfectly. We first determine the intermediate image of the object point under the most left spherical surface as if the other surfaces are not present and use this intermediate image point as object point for imaging by the next spherical surface and so on. Of course, the intermediate image and object points can be virtual.

Although this procedure is in principle simple, it is nevertheless convenient in Gaussian geometrical optics to introduce the concept of ray vectors and ray matrices to deal with optical system consisting of several spherical surfaces. With ray matrices it is easy to derive how the distance of a given ray to the optical axis and its direction change during propagation through an optical system. This in turn can be used to determine the image plane in an optical system for a given object plane.

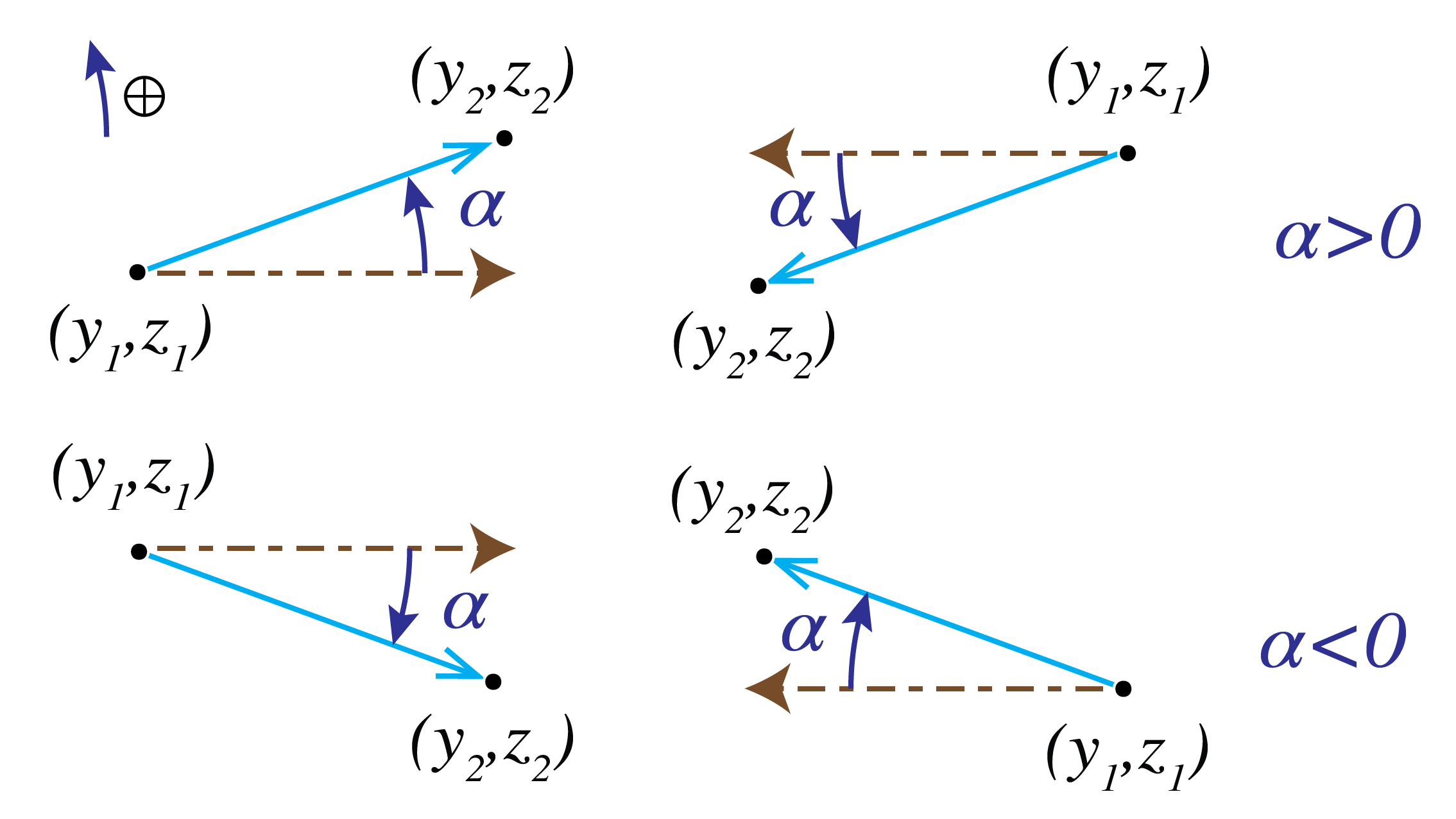

In any plane perpendicular to the \(z\)-axis, a ray is determined by the \(y\)-coordinate of the point of intersection of the ray with the plane and the angle \(\alpha\) with the optical (\(z\))-axis. This angle has a sign and is defined as follows. Let \((y_1,z_1)\) and \((y_2,z_2)\) be the coordinates of two points on the ray and let the light propagate from point 1 to point 2. Then we define

Examples of positive and negative \(\alpha\) are given in Fig. 24. The case \(z_2-z_1<0\) occurs when a ray propagates in the negative \(z\)-direction after it has been reflected by a mirror. According to Table 2 the refractive index of the ambient medium should after the reflection be taken negative. After a second reflection due to which the ray propagates again in the positive \(z\)-direction the refractive index should be chosen positive again.

Fig. 24 Sign convention for the ray angle. In the upper two figures \(\alpha>0\) while in the lower two figures \(\alpha<0\).#

We define the ray vector

where \(n\) is the local refractive index. The definition with the refractive index as factor in the first element of the ray vector turns out to be convenient. The ray vectors of a ray in any two planes \(z=z_1\), \(z=z_2\), with \(z_2>z_1\), are related by a so-called ray matrix:

where

The elements of matrix \({\cal M}\) depend on the optical components and materials between the planes \(z=z_1\) and \(z=z_2\).

As an example consider the ray matrix that relates a ray vector in the plane immediately before the spherical surface in Fig. 20 to the corresponding ray vector in the plane immediately behind that surface. Using (175) and (177) it follows

where we have replaced \(\alpha_2\) by \(-\alpha_2\) in (175), because according to the sign convention, the angle \(\alpha_2\) in Fig. 20 should be taken negative. Because furthermore \(y_2=y_1\), we conclude

where

is as before the power of the surface.

Next we consider a spherical mirror with radius of curvature \(R\). We will show that the ray matrix between the planes just before and after the mirror is given by:

where

is the power of the mirror, \(n_1=n\) but \(n_2=-n\), because the convention is used that if a ray propagates from right to left (i.e. in the negative \(z\)-direction), the refractive index in the ray vectors and ray matrices is chosen negative. Note that when the mirror is flat: \(R=\infty\), the ray matrix of the reflector implies

which agrees with the fact that \(n_2=-n_1\) and according to (183) \(\alpha_2\) and \(\alpha_1\) have opposite sign for a mirror.

Fig. 25 Reflection by a mirror.#

With all angles positive for the moment, it follows from Fig. 25

Hence,

Now

In the situation drawn in Fig. 25, (183) implies that both \(\alpha_2\) and \(\alpha _1\) are positive. By choosing the refractive index negative after reflection, we conclude from (194) and (195):

This proves Eq. (190).

We now consider the ray matrix when a ray propagates from a plane \(z_1\) to a plane \(z_2\) through a medium with with refractive index \(n\). In that case we have \(\alpha_2=\alpha_1\) and \(y_2=y_1 + \alpha_1(z_2-z_1)\), hence

Note that if the light propagates from the left to the right: \(z_2>z_1\) and hence \(z_2-z_1\) in the first column and second row of the matrix is positive, i.e. it is the distance between the planes.

For two planes between which there are a number of optical components, possibly separated by regions with homogeneous material (e.g. air), the ray matrix can be obtained by multiplying the matrices of the individual components and of the homogeneous regions. The order of the multiplication of the matrices is such that the right-most matrix corresponds to the first component that is encountered while propagating, and so on.

In the ray matrix approach all rays stay in the same plane, namely the plane through the ray and the \(z\)-axis. These rays are called meridional rays. By considering only meridional rays, the imaging by optical systems is restricted to two dimensions. Non-meridional rays are called skew rays. Skew rays do not pass through the optical axis and are not considered in the paraxial theory.

Remarks.

In matrix (197) \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) are coordinates, i.e. they have a sign.

Instead of choosing the refractive index negative in ray vectors of rays that propagate from right to left, one can reverse the direction of the positive \(z\)-axis after every reflection. The convention to make the refractive index negative is however more convenient in ray tracing software.

The determinant of the ray matrices (188), (190) and (197) are all 1. Since all ray matrices considered below are products of these elementary matrices, the determinant of every ray matrix considered is unity.

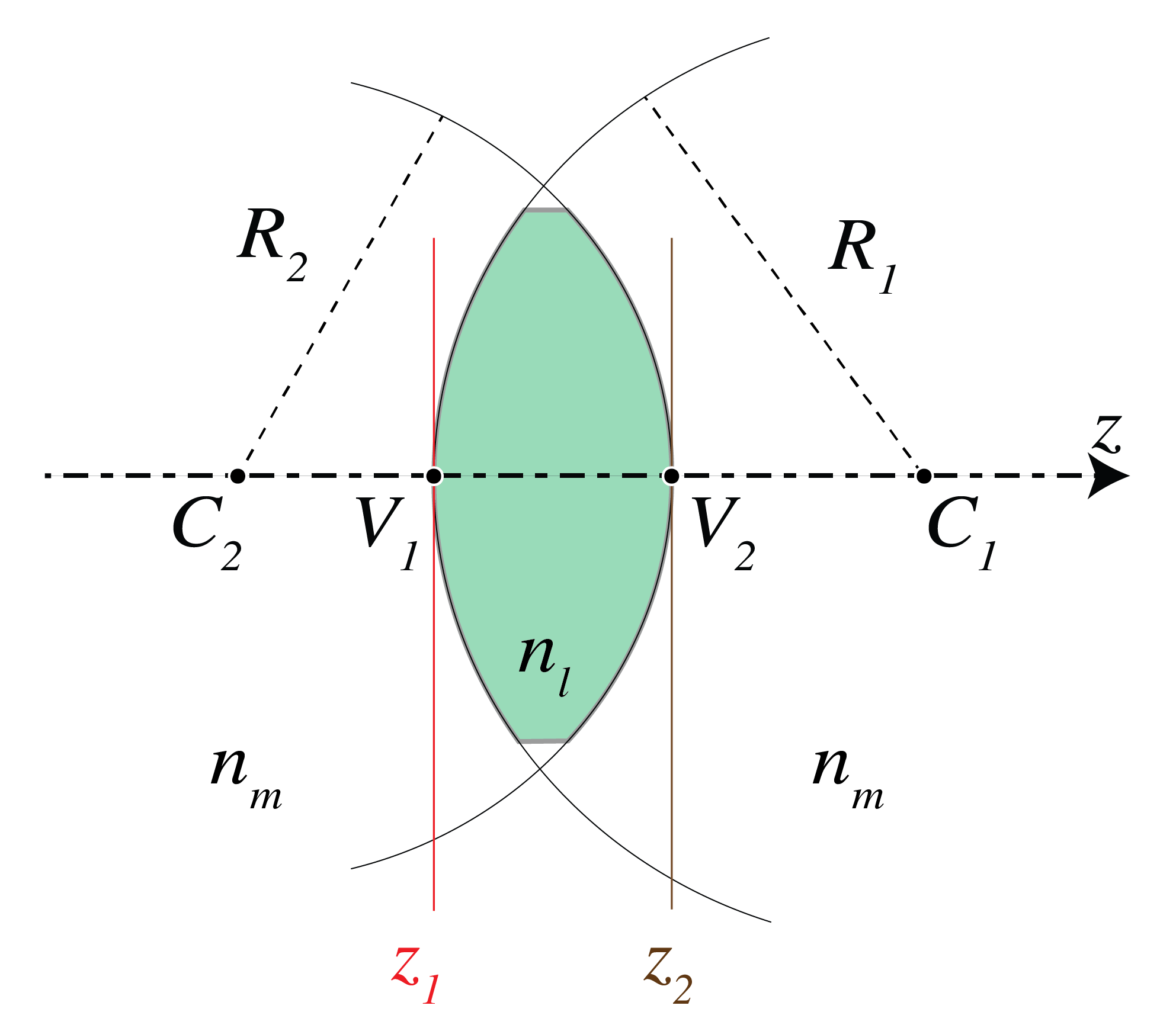

The Lens Matrix#

We apply ray matrices to a lens. Fig. 26 shows a lens with two spherical surfaces. The refractive index of the lens is \(n_l\) and that of the media to the left and to the right of the lens is \(n_1\) and \(n_2\), respectively. Let the distance between the vertices be \(d\).

Fig. 26 A lens with thickness \(d\). The ray matrix is defined between the planes immediately before and after the lens.#

We will first derive the matrix which maps the ray vector in the plane immediately in front of the lens to that in the plane immediately behind the lens. Let

be two vectors in the two planes which correspond to the same ray. The ray is first refracted by the spherical surface with radius \(R_1\) and centre \(C_1\). Using (188) and (189) it follows that the matrix between the ray vectors just before and just behind the spherical surface with radius \(R_1\) and centre \(C_1\) is given by

, where

The ray propagates then over the distance \(d\) through the material of which the lens is made. The matrix that maps ray vectors from the plane inside the lens immediately behind the left spherical surface to a ray vector in the plane immediately before the right spherical surface follows from (197):

Finally, the matrix that maps ray vectors from the plane in the lens immediately before the second spherical surface to vectors in the plane immediately behind it is

with

Hence the matrix that maps ray vectors in the plane immediately before the lens to ray vectors in the plane immediately behind the lens is given by the matrix product:

The quantity

is called the power of the lens. It has dimension 1/length and is given in diopter (\({\cal D}\)), where \(1 \,\, {\cal D}=\text{m}^{-1}\). The power can be positive and negative. The space to the left of the lens is called the object space and that to the right of the lens is called the image space.

Focusing with a Thin Lens#

For a thin lens the vertices \(V_1\) and \(V_2\) coincide and \(d=0\), hence (204) becomes

where

The origin of the coordinate system is chosen in the common vertex \(V_1=V_2\).

By considering a ray in medium 1 which is parallel to the optical axis (\(\alpha_1=0\)) and at height \(y_1\), we get \(n_2 \alpha_2= - Py_1\) and \(y_2=y_1\). Hence, when \(P>0\), the angle \(\alpha_2\) of the ray has sign opposite to \(y_2\) and therefore the ray in image space is bent back to the optical axis, yielding a second focal point or image focal point \(F_i\). Its \(z\)-coordinate \(f_i\) s:

For a ray emerging in image space at height \(y_2\) and parallel to the optical axis: \(\alpha_2=0\), we have \(y_1=y_2\) and

If the power is positive: \({\cal P}>0\), the angle \(\alpha_1\) has the same sign as \(y_1\), which implies that the ray in object space has intersected the optical axis in a point \(F_o\) with \(z\)-coordinate: \(z=f_o\)

The point \(F_o\) is called the first focal point or object focal point.

We conclude that when the power \({\cal P}\) of the lens is positive, \(f_i>0\) and \(-f_o>0\), which means that the image and object focal points are in the image and object space, respectively, hence they are both real. A lens with positive power is called convergent or positive. It makes incident bundles of rays convergent or less divergent.

A lens with negative power is called divergent and has \(f_i<0\), \(-f_o<0\). It makes incident rays more divergent or less convergent. Incident rays which are parallel to the optical axis are refracted away from the optical axis and seem to come from a point in front of the lens with \(z\)-coordinate \(f_i<0\). Hence the image focal point does not correspond to a location where there is an actual concentration of light intensity, i.e. it is virtual. The object focal point is a virtual object point, because only a bundle of incident rays that are converging to a certain point behind the negative lens can be turned into a bundle of rays parallel to the optical axis.

With the results obtained for the focal coordinates we can rewrite the lens matrix of a thin lens as

Imaging with a Thin Lens#

We first consider a general ray matrix (185), (186) between two planes \(z=z_1\) and \(z=z_2\) and ask the following question: what are the properties of the ray matrix such that the two planes are images of each other, or (as this is also called) are each other’s conjugate? Clearly for these planes to be each other’s image, we should have that for every point coordinate \(y_1\) in the plane \(z=z_1\) there is a point with some coordinate \(y_2\) in the plane \(z=z_2\) such that any ray through \((y_1,z_1)\) (within some cone of rays) will pass through point \((y_2,z_2)\). Hence for any angle \(\alpha_1\) (in some interval of angles) there is an angle \(\alpha_2\) such that (185) is valid. This means that for any \(y_1\) there is a \(y_2\) such that for all angles \(\alpha_1\):

This requires that

The ratio of \(y_2\) and \(y_1\) IS the magnification \(M\). Hence,

is the magnification of the image (this quantity has sign).

To determine the image by a thin lens we first derive the ray matrix between two planes \(z=z_1<0\) and \(z=z_2>0\) on either side of the thin lens. The origin of the coordinate system is again at the vertex of the thin lens. This ray matrix is the product of the matrix for propagation from \(z=z_1\) to the plane immediately in front of the lens, the matrix of the thin lens and the matrix for propagation from the plane immediately behind the lens to the plane \(z=z_2\):

The imaging condition (212) implies:

where we have written \(s_o=z_1\) and \(s_i=z_2\) for the \(z\)-coordinates of the object and the image. Because for the thin lens matrix (214): \(D=1-z_2/f_i\), it follows by using (215) that the magnification (213) is given by

where we have written now \(y_o\) and \(y_i\) instead of \(y_1\) and \(y_2\), respectively.

Remark. The Lensmaker’s formula for imaging by a thin lens can alternatively be derived by using the imaging formula (171) of the two spherical surfaces of the lens. We first image a given point \(S\) by the left spherical surface using (171) as if the second surface were absent. The obtained intermediate image \(P'\) is then imaged by the second spherical surface as if the first surface were absent. \(P'\) can be a real or virtual object for the second surface. The derivation is carried out in Problem 2.5.

Analogous to the case of a single spherical surface, an image is called a real image if it is to the right of the lens (\(s_i>0\)) and is called a virtual image when it seems to be to the left of the lens (\(s_i<0\)). An object is called a real object if it is to the left of the lens (\(s_o<0\)) and is a virtual object if it seems to be right of the lens (\(s_o>0\)). For a positive lens: \({\cal P}>0\) and hence (215) implies that \(s_i>0\) provided \(|s_o|>|f_o|\), which means that the image by a convergent lens is real if the object is further from the lens than the object focal point \(F_o\). The case \(s_o>0\) corresponds to a virtual object, i.e. to the case of a converging bundle of incident rays, which for an observer in object space seems to converge to a point at distance \(s_o\) behind the lens. A convergent lens (\(f_i>0\)) will then make an image between the lens and the second focal point. In contrast, a diverging lens (\(f_i<0\)) can turn the incident converging bundle into a real image only if the virtual object point is between the lens and the focal point. If the virtual object point has larger distance to the lens, the convergence of the incident bundle is too weak and the diverging lens then refracts this bundle into a diverging bundle of rays which seem to come from a virtual image point in front of the lens (\(s_i<0\)).

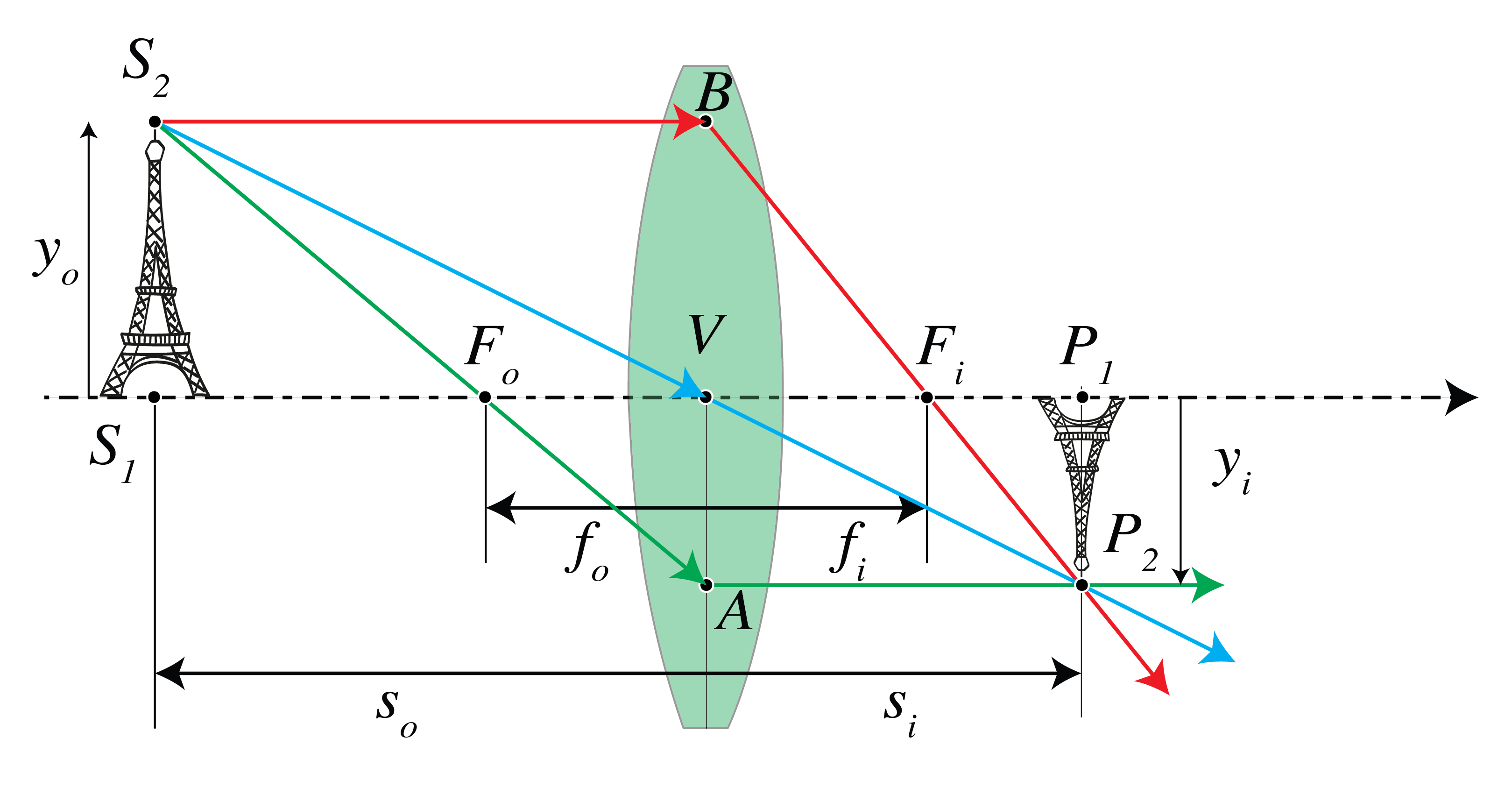

Instead of using ray matrices, one can construct the image with a ruler. Consider the imaging of a finite object \(S_1S_2\) as shown in Fig. 27 for the case that the media to the left and right lens are the same. Let \(y_o\) be the y-coordinate of \(S_2\). We have \(y_o>0\) when the object is above the optical axis.

Fig. 27 Object and image for a thin lens.#

Draw the ray through the focal point \(F_o\) in object space and the ray through the centre \(V\) of the lens. The first ray becomes parallel in image space. The latter intersects both surfaces of the lens almost in their (almost coinciding) vertices and therefore the refraction is opposite at both surfaces and the ray exits the lens parallel to its direction of incidence. Furthermore, its lateral displacement can be neglected because the lens is thin. (Of course, this is not correct when the refractive indices to the left and right of the lens are different). Hence, the ray through the centre of a thin lens is not refracted. The intersection in image space of the two rays gives the location of the image point \(P_2\) of \(S_2\). The image is real if the intersection occurs in image space and is virtual otherwise. For the case of a convergent lens with a real object with \(y_o>0\) as shown in Fig. 27, it follows from the similar triangles \(\Delta\,\text{BV}\text{F}_i\) and \(\Delta\, \text{P}_2\text{P}_1\text{F}_i\) that

. From the similar triangles \(\Delta\, \text{S}_2\text{S}_1\text{F}_o\) and \(\Delta\, \text{AVF}_o\):

here we used \(|f_o|=f_i\). (the absolute value of \(y_i\) is taken because according to our sign convention \(y_i\) in Fig. 27 is negative whereas (218) is a ratio of lengths). By multiplying these two equations we get the Newtonian form of the lens equation (valid when \(n_2=n_1\)):

where \(x_o\) and \(x_i\) are the \(z\)-coordinates of the object and image relative to those of the first and second focal point, respectively:

Hence \(x_o\) is negative if the object is to the left of \(F_o\) and \(x_i\) is positive if the image is to the right of \(F_i\).

The transverse magnification is

where the second identity follows from considering the similar triangles \(\Delta \text{P}_2\text{P}_1\text{F}_i\) and \(\Delta \text{BVF}_i\) in Fig. 27. A positive \(M\) means that the image is erect, a negative \(M\) means that the image is inverted.

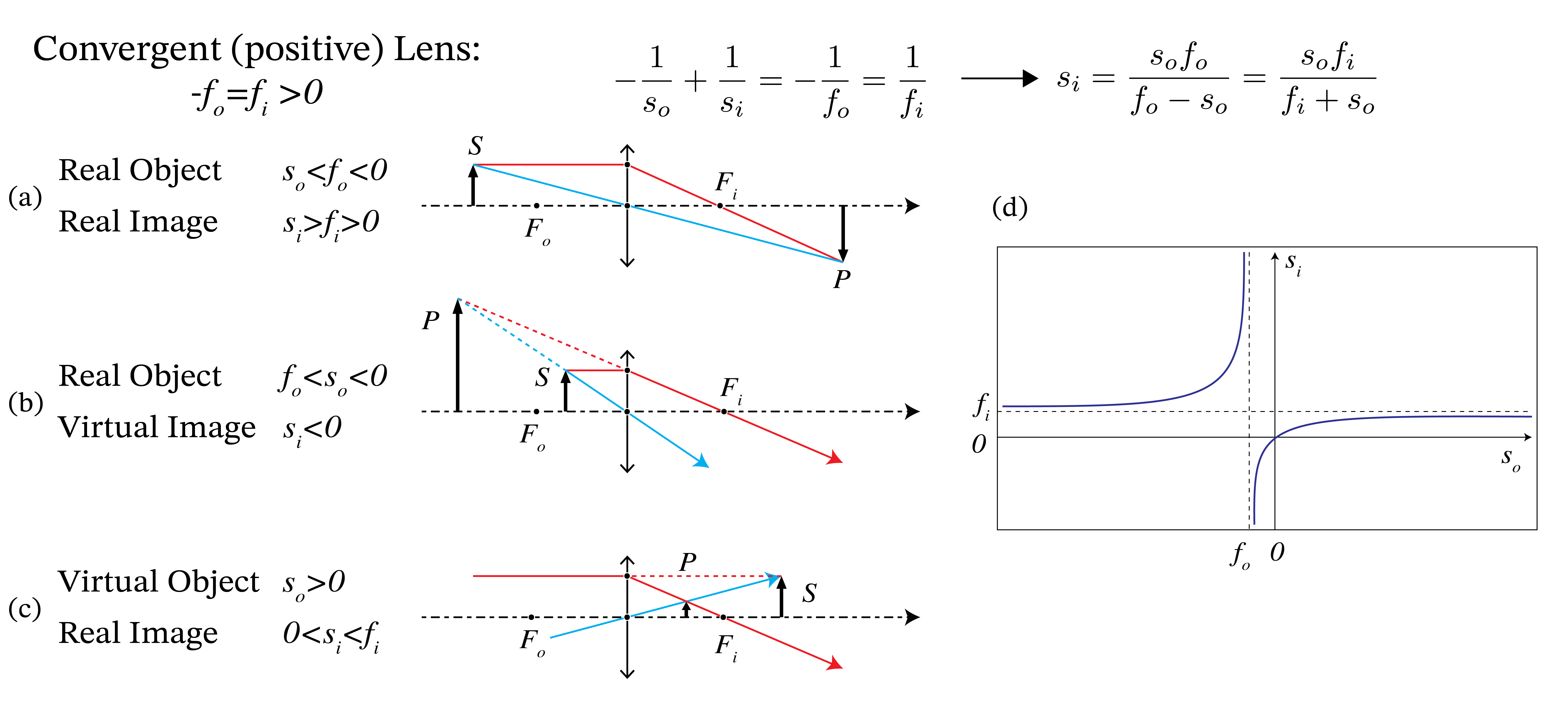

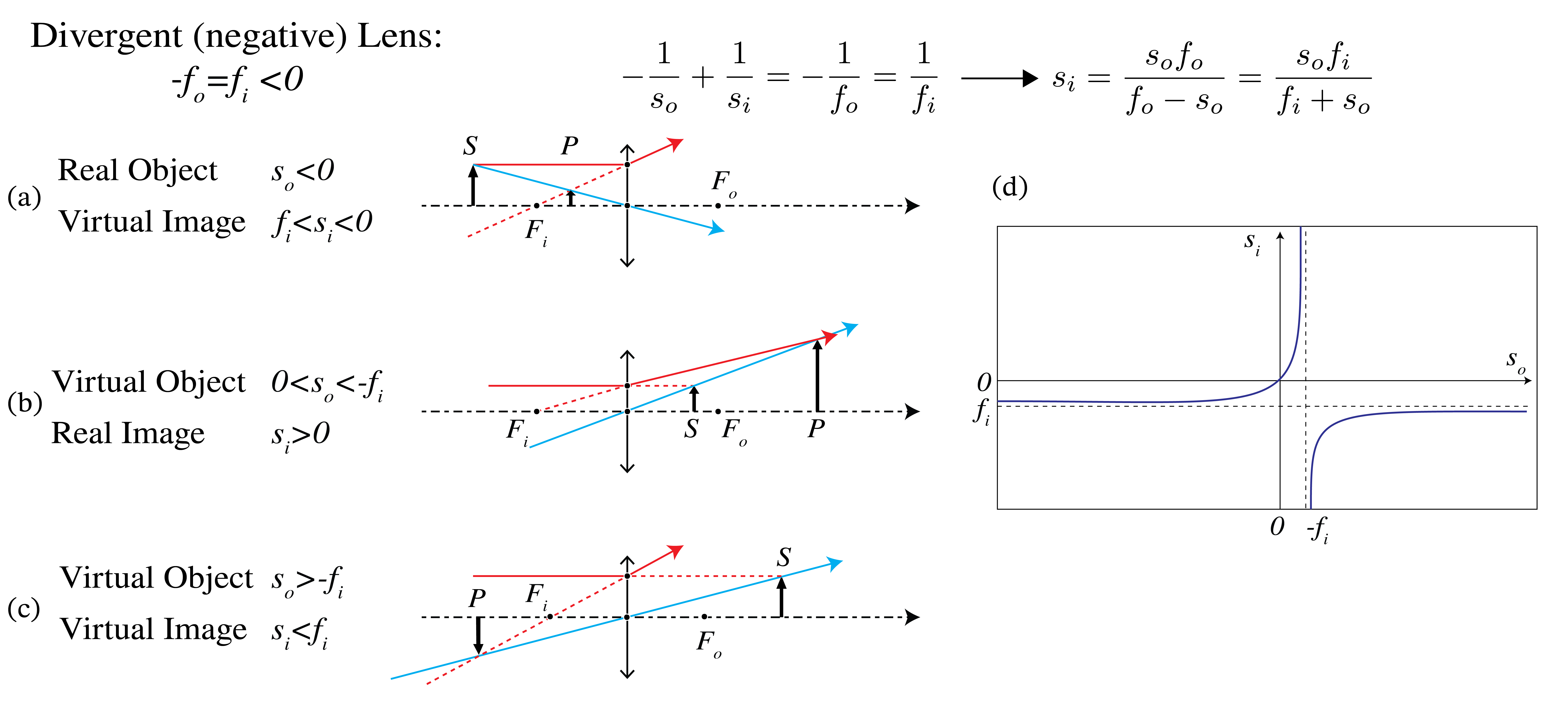

All equations are also valid for a thin negative lens and for virtual objects and images. Examples of real and virtual object and image points for a positive and a negative lens are shown in Fig. 28 and Fig. 29.

Fig. 28 Real and virtual objects and images for a convergent thin lens with the same refractive index left and right of the lens, i.e. \(-f_o=f_i>0\). In (a) the object is real with \(s_o<f_o\) and the image is real as well (\(s_i>0\)). In (b) the object is between the front focal point and the lens: \(f_o< s_o<0\). Then the rays from the object are too divergent for the lens to make them convergent in image space and hence the image is virtual: \(s_i<0\). In (c) there is a cone of converging rays incident on the lens from the left which, in the absence of the lens, would converge to point \(S\) behind the lens. Therefore \(S\) is a virtual object (\(s_0>0\)). The image is real and can be constructed with the two rays shown. In (d) \(s_i\) is shown as function of \(s_o\) for a convergent lens (see Eq. (215)).#

Fig. 29 Real and virtual objects and images for a divergent thin lens with the same refractive index to the left and right of the lens, i.e. \(-f_o=f_i<0\). In (a) the object is real, i.e. \(s_o<0\). The diverging lens makes the cone of rays from the object more divergent so that the image is virtual: \(s_i<0\). When the object is virtual, there is a cone of converging rays incident from the left which after extension to the right of the lens (as if the lens is not present) intersect in the virtual object S (\(s_o>0\)). It depends on how strong the convergence is whether the diverging lens turns this cone into converging rays or whether the rays keep diverging. In (b) \(0<s_o<-f_i\), and the image is real. In c) \(s_o>-f_i\) and the image is virtual (\(s_i<0\)). In (d) \(s_i\) is shown as function of \(s_o\) for a divergent lens (\(f_i<0\) (see Eq. (215)).#

Two Thin Lenses#

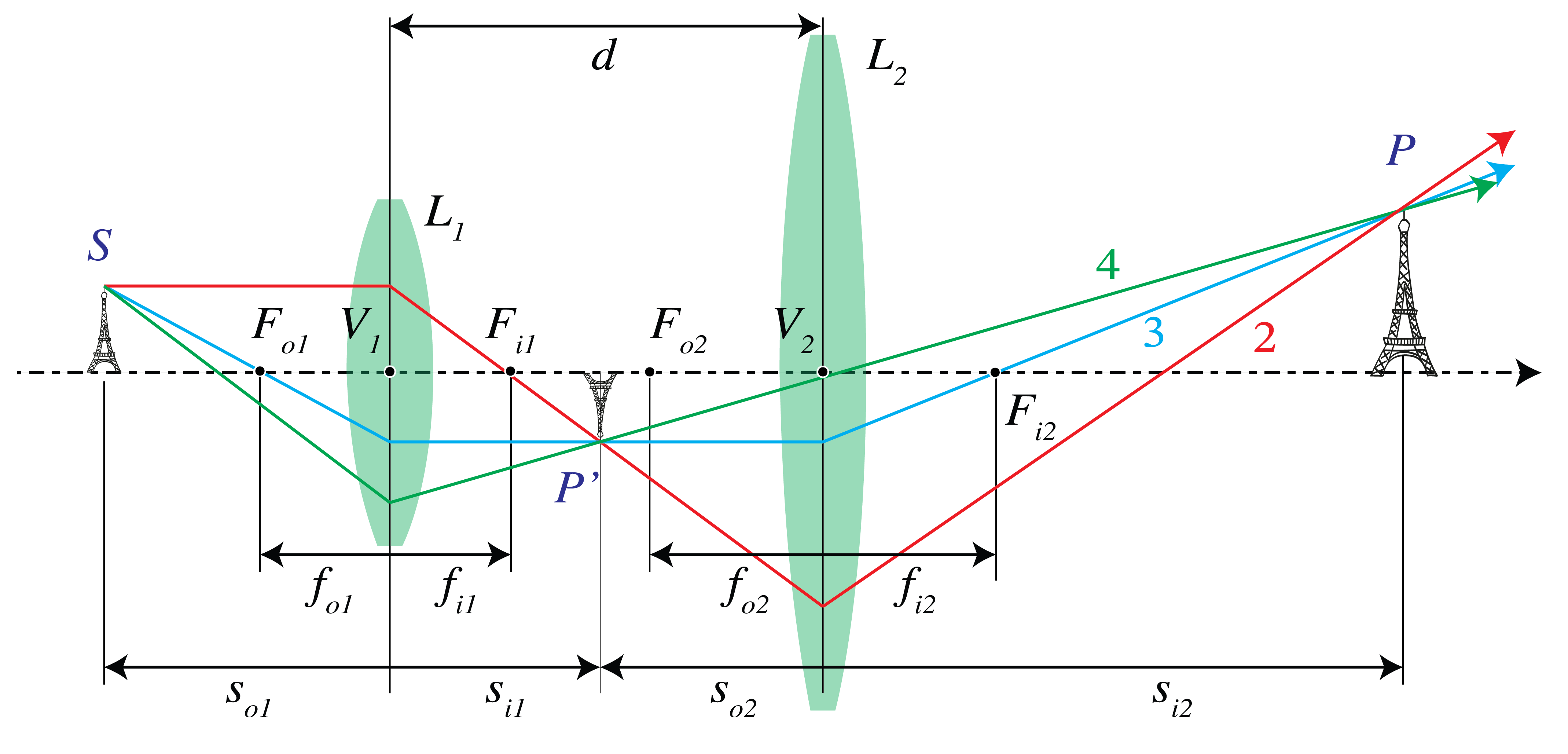

The ray matrix is a suitable method to study the imaging of a system consisting of several thin lenses. For two lenses however, the imaging can still easily be obtained by construction. We simply construct the image obtained by the first lens as if the second lens were not present and use this image as (possibly virtual) object for the second lens. In Fig. 30 an example is shown where the distance between the lenses is larger than the sum of their focal lengths. First the image \(P'\) of \(S\) is constructed as obtained by \(L_1\) as if \(L_2\) were not present. We construct the intermediate image \(P'\) due to lens \(L_1\) using ray 2 and 3. \(P'\) is a real image for lens \(L_1\) and also a real object for lens \(L_2\). Ray 3 is parallel to the optical axis between the two lenses and is thus refracted by lens \(L_2\) through its back focal point \(F_{2i}\). Ray 4 is the ray from \(P'\) through the centre of lens \(L_2\). The image point \(P\) is the intersection of ray 3 and 4.

Fig. 30 Two thin lenses separated by a distance that is larger than the sum of their focal lengths.#

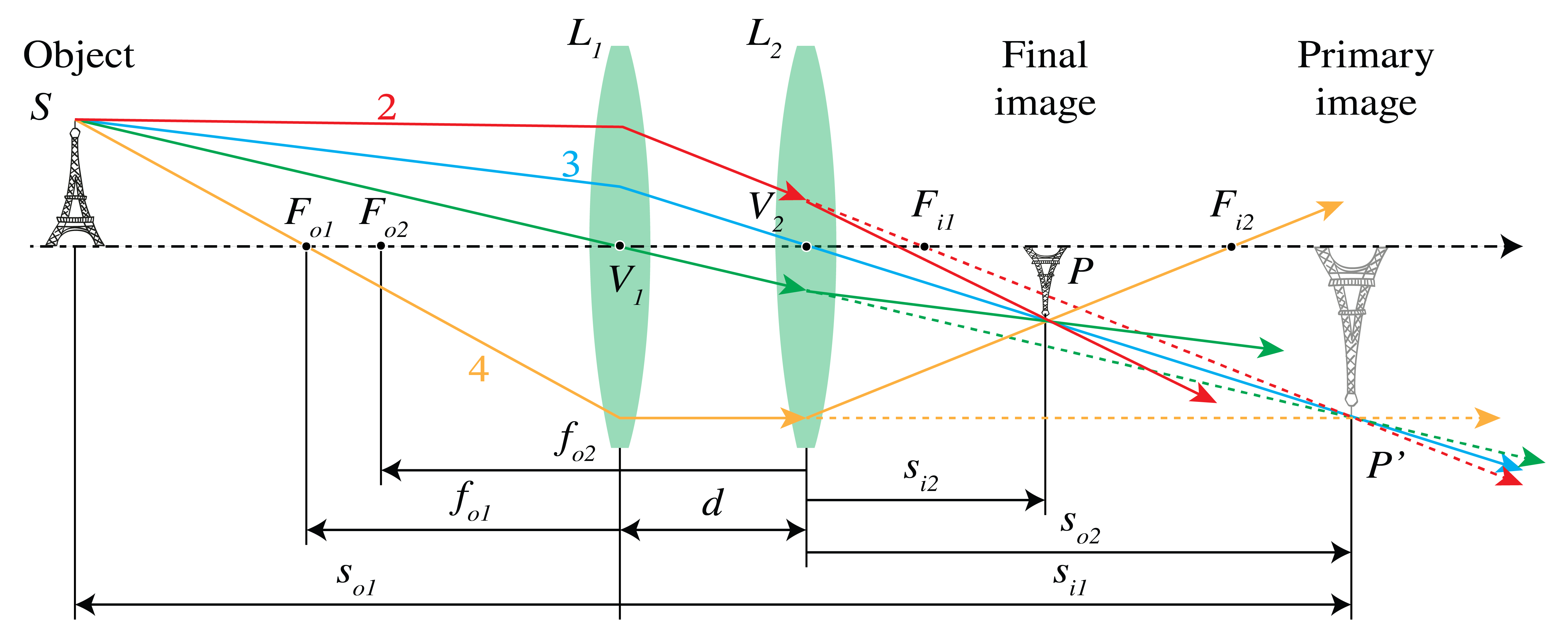

In the case of Fig. 31 the distance \(d\) between the two positive lenses is smaller than their focal lengths. The intermediate image \(P'\) is a real image for \(L_1\) obtained as the intersection of rays 2 and 4 passing through the object and image focal points \(F_{o1}\) and \(F_{i1}\) of lens \(L_1\). \(P'\) is now a virtual object for lens \(L_2\). To find its image by \(L_2\), draw ray 3 from \(P'\) through the centre of lens \(L_2\) back to \(S\) (this ray is refracted by lens \(L_1\) but not by \(L_2\)) and draw ray 4 as refracted by lens \(L_2\). Since ray 4 is parallel to the optical axis between the lenses, it passes through the back focal point \(F_{2i}\) of lens \(L_2\). The intersection point of ray 3 and 4 is the final image point \(P\).

Fig. 31 Two thin lenses at a distance smaller than their focal lengths.#

It is easy to express the \(z\)-coordinate \(s_i\) with respect to the coordinate system with origin at the vertex of \(L_2\) of the final image point, in the \(z\)-component \(s_o\) with respect to the origin at the vertex of lens \(L_1\) of the object point. We use the Lensmaker’s Formula for each lens while taking care that the proper local coordinate systems are used. The intermediate image \(P'\) due to lens \(L_1\) has \(z\)-coordinate \(s_{1i}\) with respect to the coordinate system with origin at the vertex \(V_1\), which satisfies:

As object for lens \(L_2\), \(P'\) has \(z\)-coordinate with respect to the coordinate system with origin at \(V_2\) given by: \(s_{2o}=s_{1i}-d\), where \(d\) is the distance between the lenses. Hence, with \(s_i=s_{2i}\) the Lensmaker’s Formula for lens \(L_2\) implies:

By solving (222) for \(s_{1i}\) and substituting the result into (223), we find

By taking the limit \(s_o \rightarrow -\infty\), we obtain the \(z\)-coordinate \(f_i\) of the image focal point of the two lenses, while \(s_i\rightarrow \infty\) gives the \(z\)-coordinate \(f_o\) of the object focal point:

We found in Focusing with a Thin Lens that when the refractive indices of the media before and after the lens are the same, the object and image focal lengths of a thin lens are the identical. However, as follows from (225) and (226) the object and image focal lengths are in general different when there are several lenses.

By construction using the intermediate image, it is clear that the magnification of the two-lens system is the product of the magnifications of the two lenses:

Remarks.

When \(f_{1i}+f_{2i}=d\) the focal points are at infinity. Such a system is called telecentric.

In the limit where the lenses are very close together: \(d\rightarrow 0\), (224) becomes

The focal length \( f_i\) of the system of two lenses in contact thus satisfies:

In particular, by the using two identical lenses in contact, the focal length is halved.

Although for two lenses the image coordinate can still be expressed relatively easily in the object distance, for systems with more lenses finding the overall ray matrix and then using the image condition (212) is a much better strategy.

The Thick Lens#

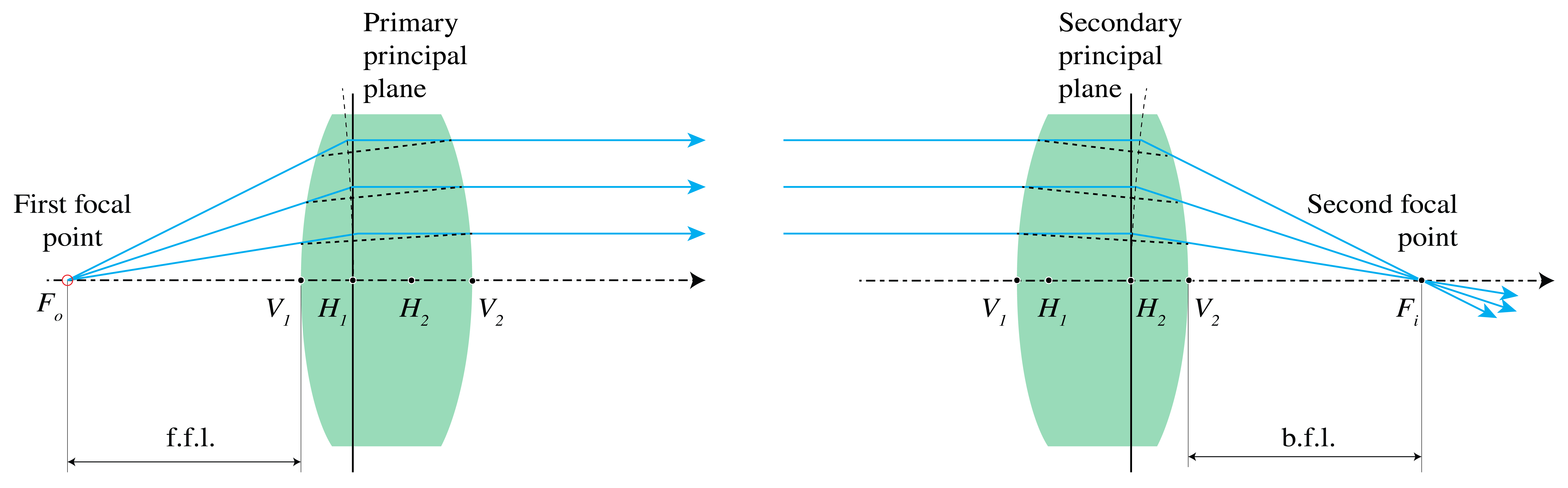

At the left of Fig. 32 a thick lens is shown. The object focal point is defined as the point whose rays are refracted such that the emerging rays are parallel to the optical axis. By extending the incident and emerging rays by straight segments, the points of intersection are found to be on a curved surface, which close to the optical axis, i.e. in the paraxial approximation, is in good approximation a plane perpendicular to the optical axis. This plane is called the primary principal plane and its intersection with the optical axis is called the primary principal point \(H_1\).

Fig. 32 Principal planes of a thick lens, with front and back focal lengths: f.f.l and b.f.l.#

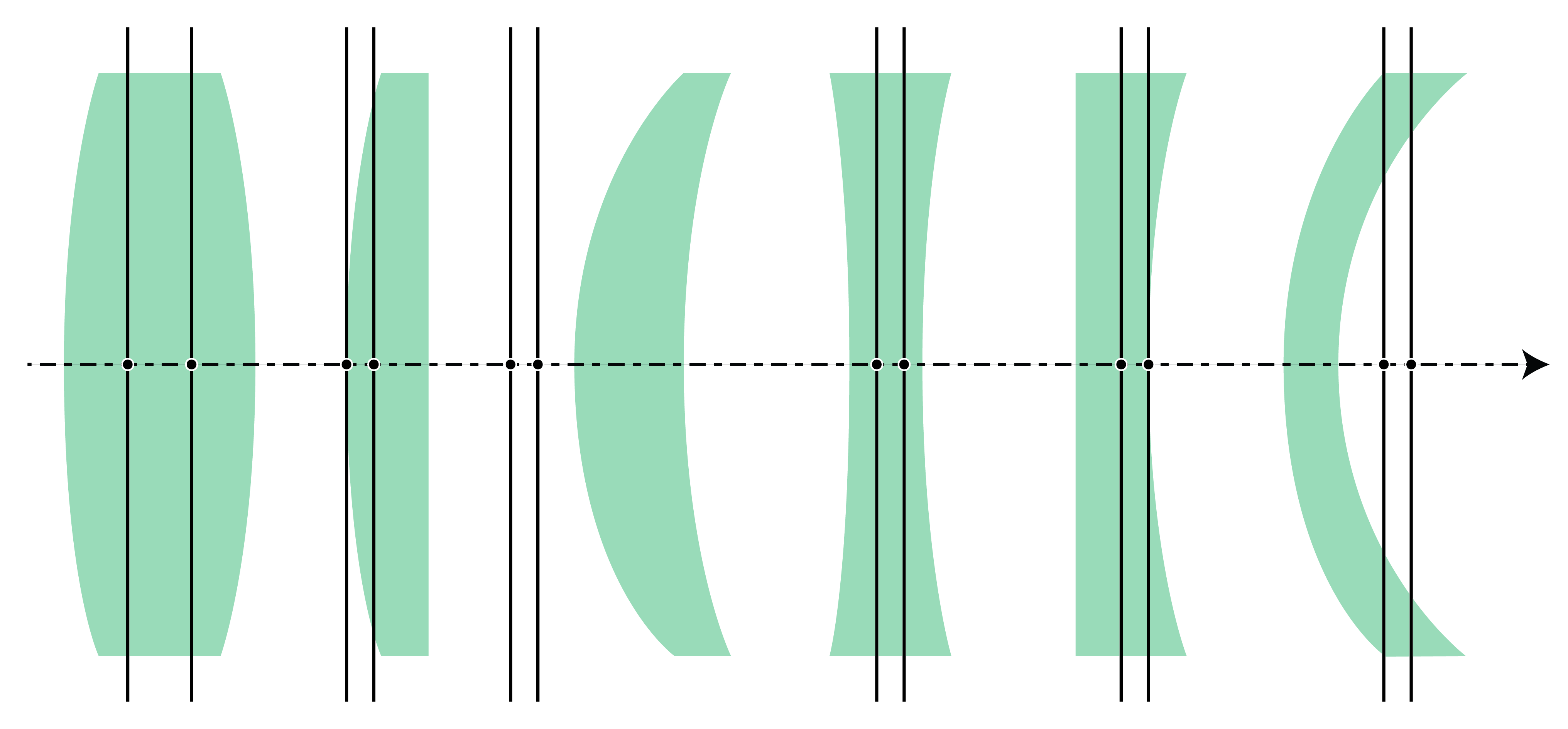

By considering incident rays which are parallel to the optical axis and therefore focused in the image focal point, the secondary principal plane and secondary principal point \(H_2\) are defined in a similar way (see the drawing at the right in Fig. 32). The principal planes can be outside the lens. For meniscus lenses, this is usually the case as shown in Fig. 33. It can be seen from Fig. 32 that the principal planes are images of each other, with unit magnification. Hence, if an object is placed in the primary principal plane (hypothetically if this plane is inside the lens), its image is in the secondary principal plane. The image is erect and has unit magnification.

Fig. 33 Position of the principal planes for several lenses.#

Now, if the object coordinates and object focal point are defined with respect to the origin at \(H_1\) and the image coordinates and image focal point are defined with respect to the origin in \(H_2\), the Lensmaker’s formula (215) can also be used for a thick lens.

Proof

We recall the result (204) for the ray matrix between the planes through the front and back vertices \(V_1\), \(V_2\) of a thick lens with refractive index \(n_l\) and thickness \(d\):

where

and \(n_1\), \(n_2\) are the refractive indices to the left and the right of the lens, respectively, and where

If \(h_1\) is the \(z\)-coordinate of the first principal point \(H_1\) with respect to the coordinate system with origin at vertex \(V_1\), we have according to (197) for the ray matrix between the primary principal plane and the plane through vertex \(V_1\)

Similarly, if \(h_2\) is the coordinate of the secondary principal point \(H_2\) with respect to the coordinate system with \(V_2\) as origin, the ray matrix between the plane through vertex \(V_2\) and the secondary principal plane is

The ray matrix between the two principle planes is then

The coordinates \(h_1\) and \(h_2\) can be found by imposing to the resulting matrix the imaging condition (212): \(C=0\) and the condition that the magnification should be unity: \(D=1\), which follows from (213). We omit the details and only give the resulting expressions here:

With these results, (235) becomes

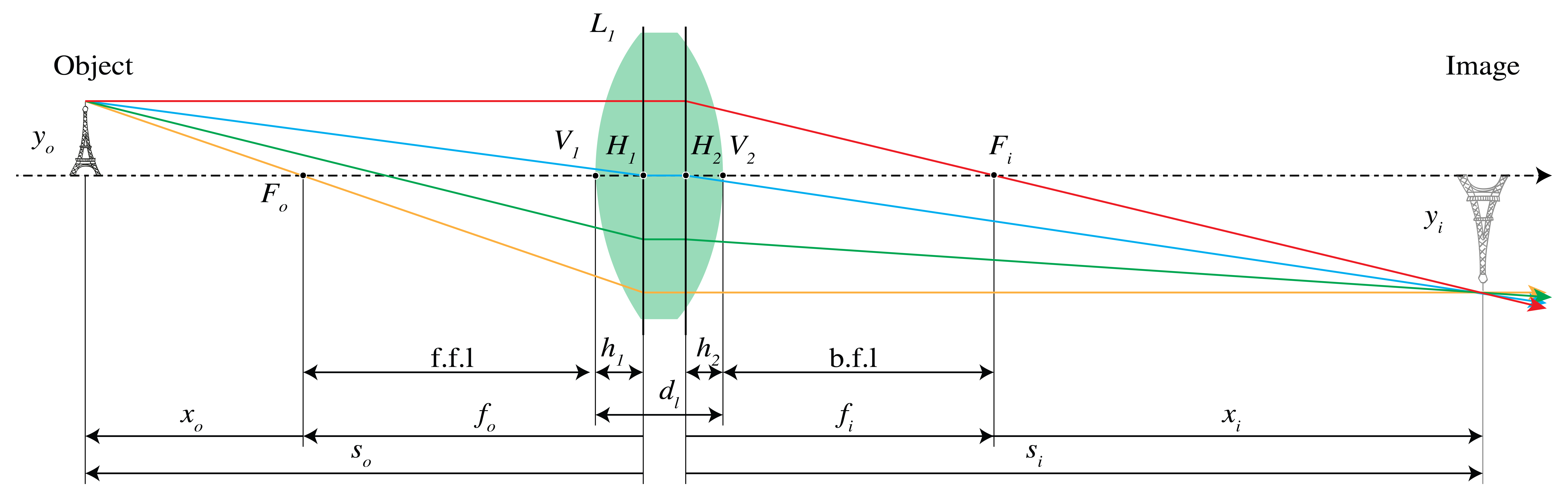

We see that the ray matrix between the principal planes is identical to the ray matrix of a thin lens (206). We therefore conclude that if the coordinates in object space are chosen with respect to the origin in the primary principal point \(H_1\), and the coordinates in image space are chosen with respect to the origin in the secondary principal point \(H_2\), the expressions for the first and second focal points and for the coordinates of the image point in terms of that of the object point are identical to that for a thin lens. An example of imaging by a thick lens is shown in Fig. 34.

Fig. 34 Thick-lens geometry. There holds \(f_i=f_o\) if the ambient medium left of the lens is the same as to the right of the lens. All coordinates in object and image space are with respect to the origin in \(H_1\) and \(H_2\), respectively.#

Stops#

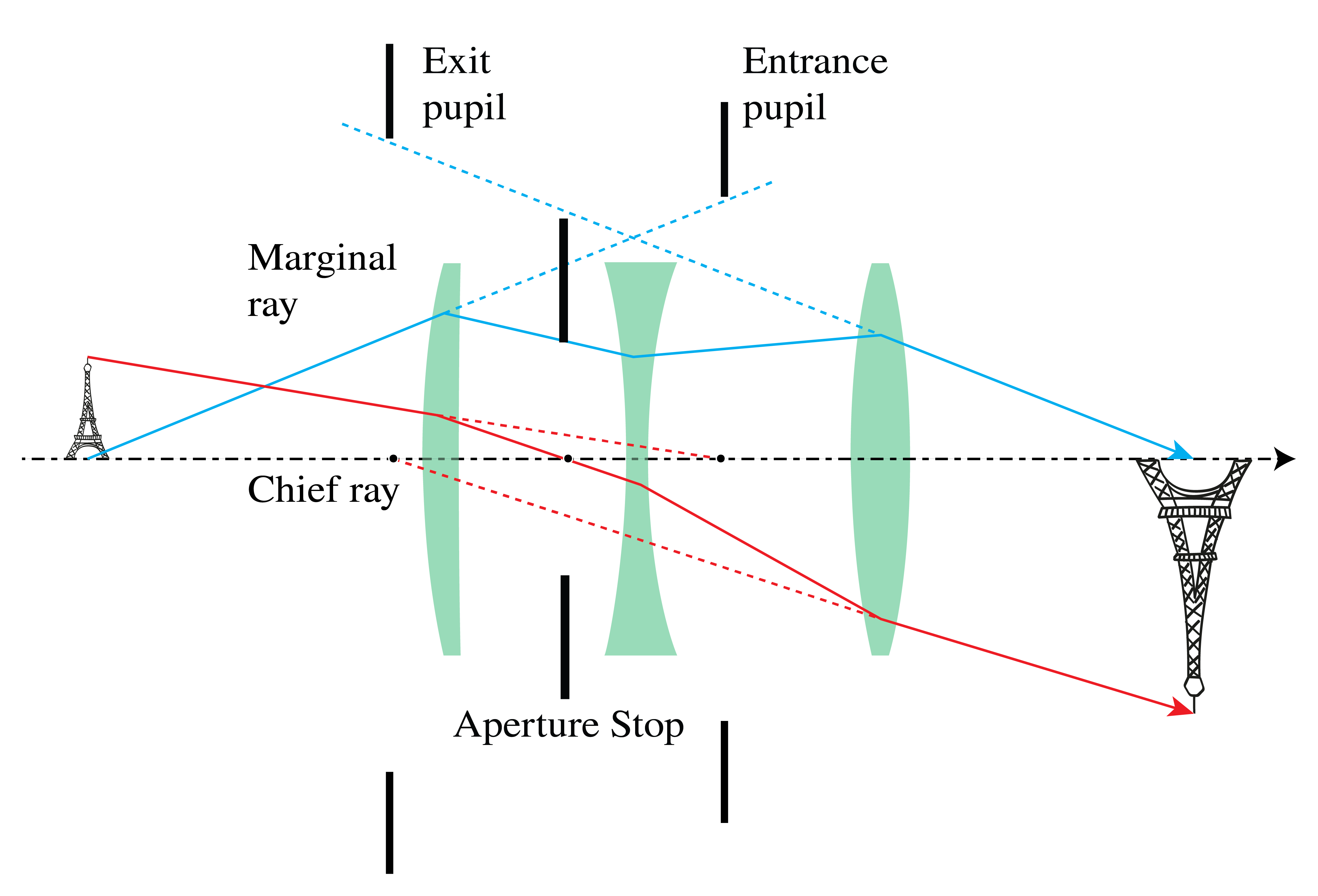

An element such as the rim of a lens or a diaphragm which determines the set of rays that can contribute to the image, is called the aperture stop. An ordinary camera has a variable diaphragm.

The entrance pupil is the image of the aperture stop by all elements to the left of the aperture stop. In constructing the entrance pupil, rays are used which propagate from the right to the left. The image can be real or virtual. If there are no lenses between object and aperture stop, the aperture stop itself is the entrance pupil. Similarly, the exit pupil is the image of the aperture stop by all elements to the right of it. This image can be real or virtual. The entrance pupil determines for a given object the cone of rays in object space that contribute to the image, while the cone of rays leaving the exit pupil are those taking part in the image formation pupil (see Fig. 35).

For any object point, the chief ray is the ray in the cone that passes through the centre of the entrance pupil, and hence also through the centres of the aperture stop and the exit pupil. A marginal ray is the ray that for an object point on the optical axis passes through the rim of the entrance pupil (and hence also through the rims of the aperture stop and the exit pupil).

For a fixed diameter \(D\) of the exit pupil and for given \(x_o\), the magnification of the system is according to (221) and (219) given by \(M=-x_i/f_i=f_i/x_o\). It follows that when \(f_i\) is increased, the magnification increases. A larger magnification means a lower energy density, hence a longer exposure time, i.e. the speed of the lens is reduced. Camera lenses are usually specified by two numbers: the focal length \(f\), measured with respect to the exit pupil and the diameter \(D\) of the exit pupil. The \(f\)-number is the ratio of the focal length to this diameter:

For example, f-number\(=2\) means \(f = 2D\). Since the exposure time is proportional to the square of the f-number, a lens with f-number 1.4 is twice as fast as a lens with f-number 2.

Fig. 35 Aperture stop (A.S.) between the second and third lens, with entrance pupil and exit pupil (in this case these pupils are virtual images of the aperture stop). Also shown are the chief ray and the marginal ray.#

Beyond Gaussian Geometrical Optics#

Aberrations#

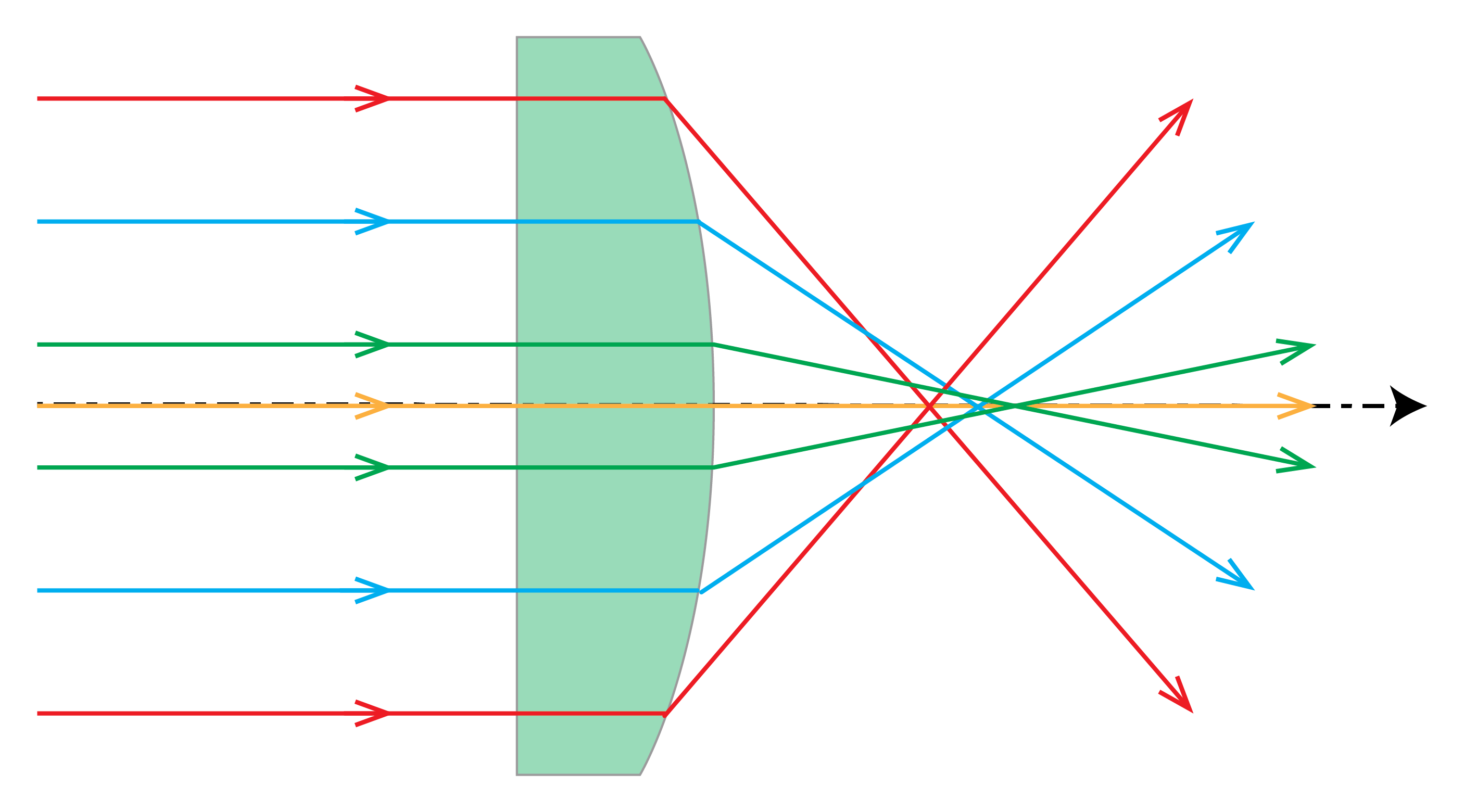

For designing advanced optical systems Gaussian geometrical optics is not sufficient. Instead non-paraxial rays, and among them also non-meridional rays, must be traced using software based on Snell’s Law with the sine of the angles of incidence and refraction. Often many thousands of rays are traced to evaluate the quality of an image. It is then found that in general the non-paraxial rays do not intersect at the ideal Gaussian image point. Instead of a single spot, a spot diagram is found which is more or less confined. The deviation from an ideal point image is quantified in terms of aberrations. One distinguishes between monochromatic and chromatic aberrations. The latter are caused by the fact that the refractive index depends on wavelength. Recall that in paraxial geometrical optics Snell’s Law (169) is replaced by: \(n_i \theta_i = n_t \theta_t\), i.e. \(\sin \theta_i\) and \(\sin \theta_t\) are replaced by the linear terms. If instead one retains the first two terms of the Taylor series of the sine, the errors in the image can be quantified by five monochromatic aberrations, the so-called primary or Seidel aberrations. The best known is spherical aberration, which is caused by the fact that for a convergent spherical lens, the rays that makes a large angle with the optical axis are focused closer to the lens than the paraxial rays (see Fig. 36).

Fig. 36 Spherical aberration of a planar-convex lens.#

Distortion is one of the five primary aberrations. It causes deformation of images due to the fact that the magnification depends on the distance of the object point to the optical axis.

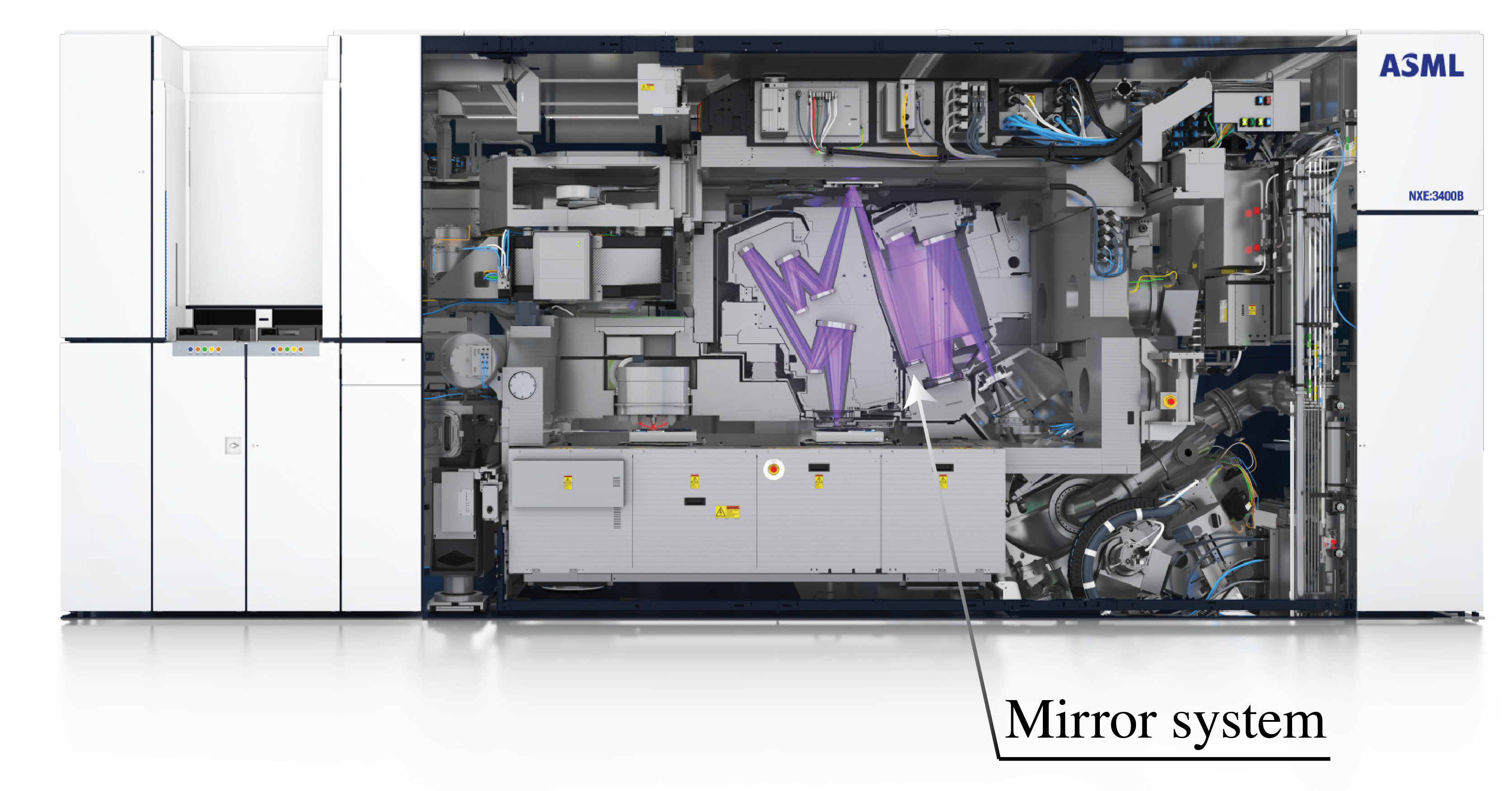

For high-quality imaging the aberrations have to be reduced by adding more lenses and optimising the curvatures of the surfaces, the thicknesses of the lenses and the distances between them. For high quality systems, a lens with an aspherical surface is sometimes used. Systems with very small aberrations are extremely expensive, in particular if the field of view is large, as is the case in lithographic imaging systems used in the manufacturing of integrated circuits as shown in the lithographic system in Fig. 37.

A comprehensive treatment of aberration theory can be found in Braat et al.[4].

Fig. 37 The EUV stepper TWINSCAN NXE:3400B.Lithographic lens system for DUV (192 nm), costing more than € 500.000. Ray paths are shown in purple. The optical system consists of mirrors because there are no suitable lenses for this wavelength (Courtesy of ASML).#

Diffraction#

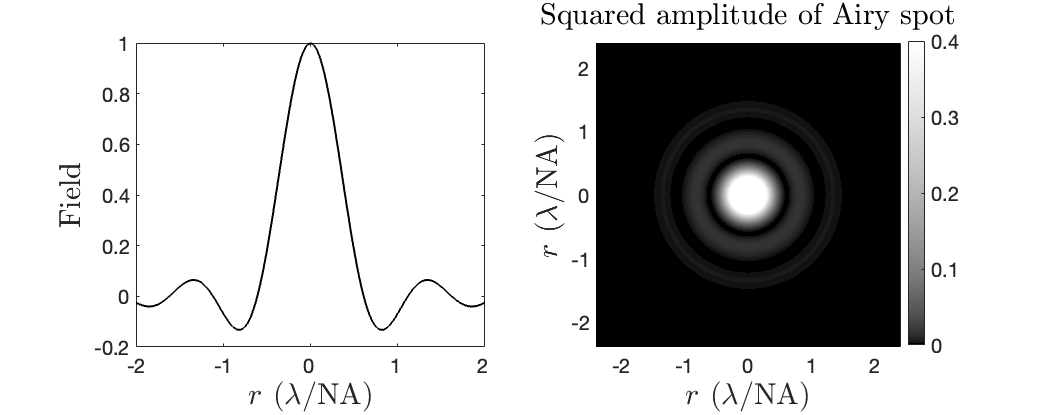

According to a generally accepted criterion formulated first by Rayleigh, aberrations start to deteriorate images considerably if the they cause path length differences of more than a quarter of the wavelength. When the aberrations are less than this, the system is called diffraction limited…

Fig. 38 Left: cross section of the field of the Airy pattern. Right: intensity pattern of the Airy pattern.#

Even if the wave transmitted by the exit pupil would be perfectly spherical (no aberrations), the wave front consists of only a circular section of a sphere since the field is limited by the aperture. An aperture causes diffraction, i.e. bending and spreading of the light. When one images a point object on the optical axis, diffraction causes inevitable blurring given by the so-called Airy spot, as shown in Fig. 38. The Airy spot has full-width at half maximum:

where NA\(=\arcsin(a/s_i)\) is the numerical aperture (i.e. 0<NA<1) with \(a\) the radius of the exit pupil and \(s_i\) the image distance as predicted by Gaussian geometrical optics. Diffraction depends on the wavelength and hence it cannot be described by geometrical optics, which applies in the limit of vanishing wavelength. We will treat diffraction by apertures in Scalar Diffraction Optics.