Optical Instruments#

After the treatment in the preceding chapter of the laws of Gaussian geometrical optics, more complex systems based on lenses and reflectors can now be considered.

The Camera Obscura#

The camera obscura or pinhole camera is the simplest image forming system. It consists of a closed box with a pinhole on one side. An inverted image is cast on the opposite side of the box as shown in Fig. 49. If the hole is too large, the image is very blurred. At the cost of less light, the image can be made sharper by reducing the aperture. The camera obscura can form images of objects across an extremely wide angular field due to great depth of focus and over a large range of distances (great depth of field) as you can see in the right picture of Fig. 49. If a film would be used to record the image, very long exposure times are however needed because only a small amount of light enters the pinhole, (f-number= 500). It is believed that painters such as Johannes Vermeer have used the camera obscura to make paintings of external scenes.

Fig. 49 The principle of the camera obscura (from Wikimedia Commons in Fizyka z. (1910) / Public Domain). Examples of pictures made with a camera obscura can be found here.#

The Camera#

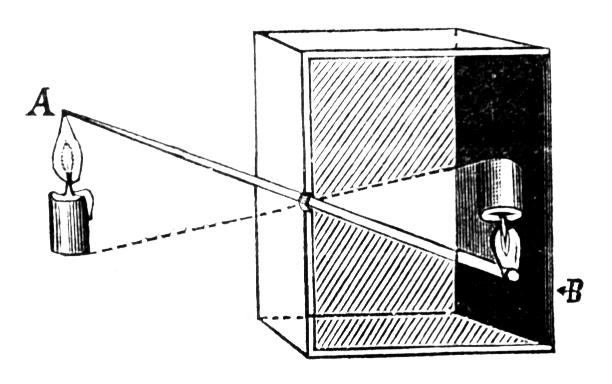

In Fig. 50 a single-lens reflex (SLR) camera is shown. The name does not mean that there is only one lens in the optical system, but that the photographer looks through the same lenses that the picture is taken with, instead of looking through a separate parallel optical system as in the twin reflex camera. After traversing the first few lens elements, the light passes through an iris diaphragm with adjustable diameter with which the \(f\)-number can be changed. After the lenses the light is reflected by a movable mirror tilted at \(45^o\), passes through a prism and exits the camera through the finder eyepiece. When the shutter is released, the diaphragm closes to a preset value, the mirror swings up and the CCD is exposed. To focus the camera, the entire lens is moved toward or away from the detection plane. Autofocus is based on maximising the contrast of the images.

Fig. 50 Digital SLR camera. The pixelated digital sensor is behind a movable mirror at angle of 45 degrees with the optical axis. (from Wikimedia Commons by Jean François WITZ / CC BY-SA 3.0).#

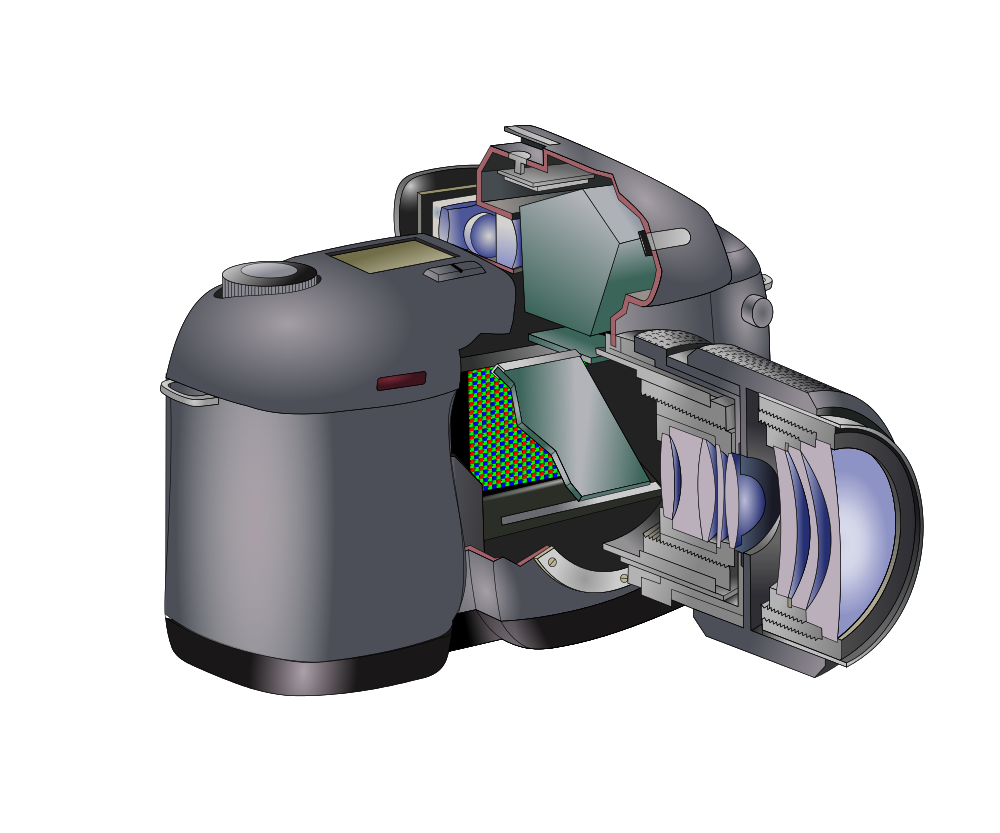

The angular field of view (AFOV) is defined for scenes at large distances and is equal to the angle subtended at the lens by the detector when the image distance is the focal length \(f\), i.e. the object is at infinity (Fig. 51). The AFOV decreases when \(f\) increases. A standard SLR has a focal length of around 6 cm with AFOV between 40° and 50°.

Fig. 51 Angular field of view#

More complex systems can have a variable focal length by changing the distance between the lenses, i.e. they are able to zoom into a scene.

The depth of focus is a range of object distances around a given distance for which the images on the sensor are sharp. The depth of focus depends on the diaphragm. When the aperture is wide open, rays forming the image will make larger angles with the optical axis. When these rays come from objects at various distances they will for a large diaphragm cause more blurred images on the sensor (see Fig. 52). When the aperture is reduced, this effect is less and therefore a smaller diaphragm implies a larger depth of focus. The drawback is that less light reaches the sensor, therefore a longer exposure time is needed.

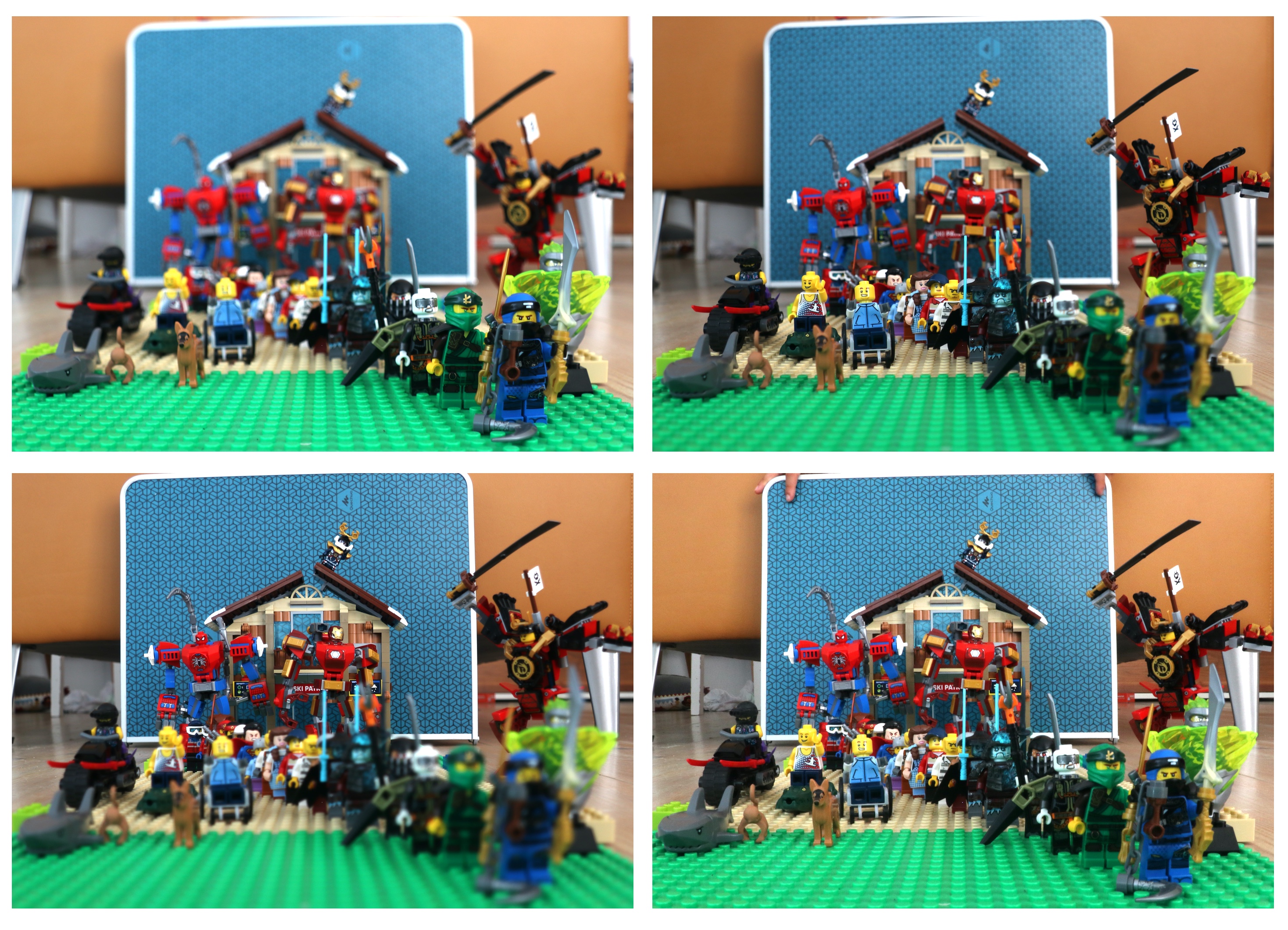

Fig. 52 Four images taken with different diaphragm and different focal plane. The image on bottom right is taken with a small diaphragm and the entire image appears clear (photos taken by Aurèle J.L. ADAM / CC BY-SA).#

Camera in a Smart Phone#

A camera in a smart phone can contain standard double Gauss or Cook triplet lenses and sometimes more advanced aspheres. The image sensor is CMOS device. Nowadays smart phones have auto-focus systems where the lens is moved towards or away from the sensor using different criteria. In the standard contrast detection auto-focus the lens is moved until the contrast in the image is largest. This trial-and-error method is relatively slow: it usually takes 1 second to focus. In high-end cameras so-called phase detection auto-focus is used where the relative position of two spots obtained by focusing of two small diaphragms on either side of the optical axis is analysed. A third auto-focus system is similar to radar. An infrared laser pulse is emitted and the distance of the object of interest is determined from the return time of the reflected pulse. The method works very well under low light conditions, but is not accurate for objects at distances of more than 5 m. In all smart phone cameras, blurry images are sharpened by post-processing using software.

The Human Eye#

The eye is an adaptive imaging system.

Anatomy#

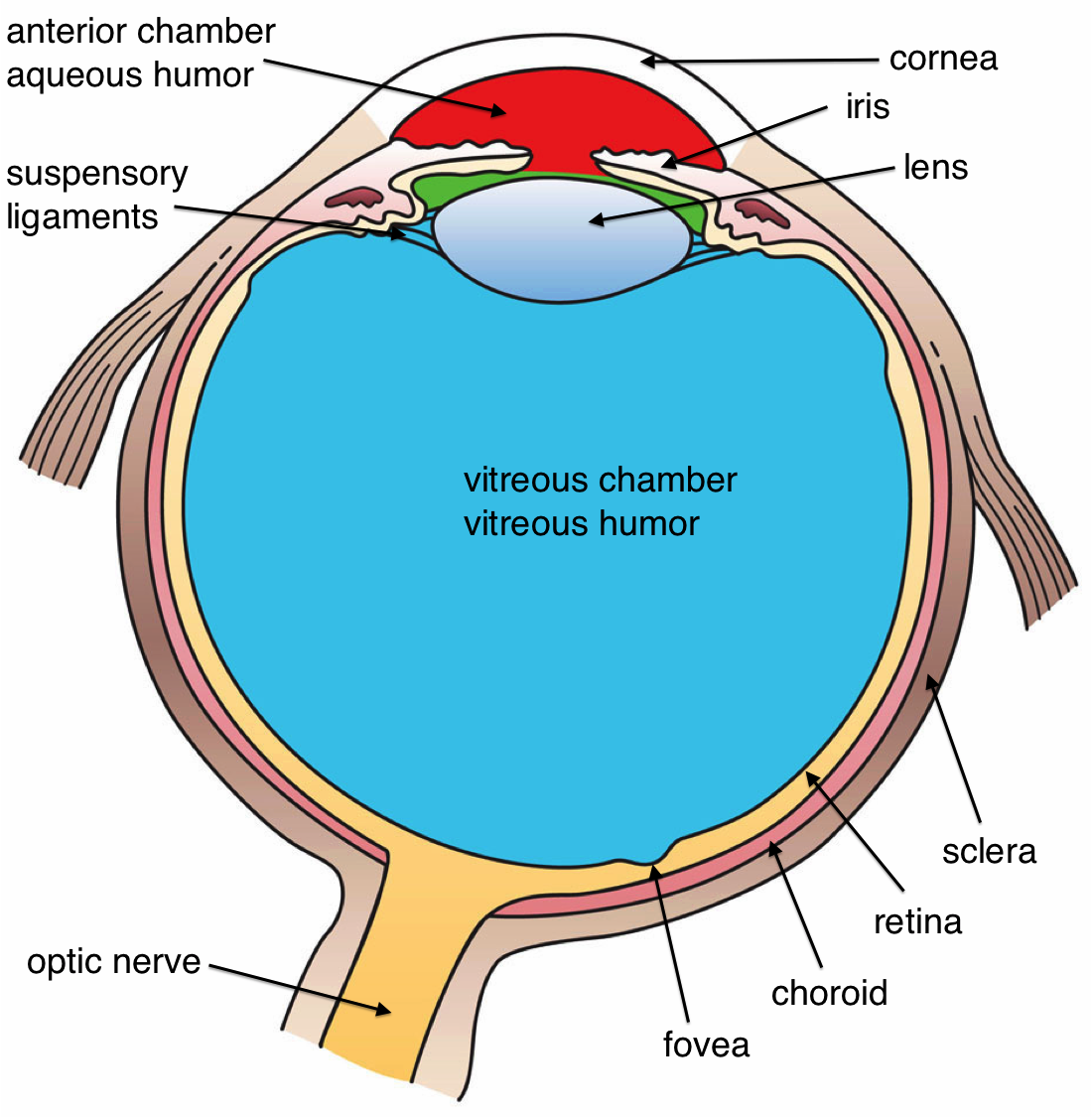

The human eye is made of an almost spherical (24 mm long and 22 mm across) gelatinous substance called the vitreous humor with refractive index 1.337, surrounded by a white shell, the sclera (Fig. 53). At the front, the sclera has an opening with a transparent lens called the cornea, with for green light an index of refraction of 1.376. Most of the bending of the rays takes place at the air-cornea interface and this is why it is difficult to see under water (\(n_{water}=1.33\)).

Fig. 53 Cross section of a human eye (from Wikimedia Commons by Holly Fischer / CC BY).#

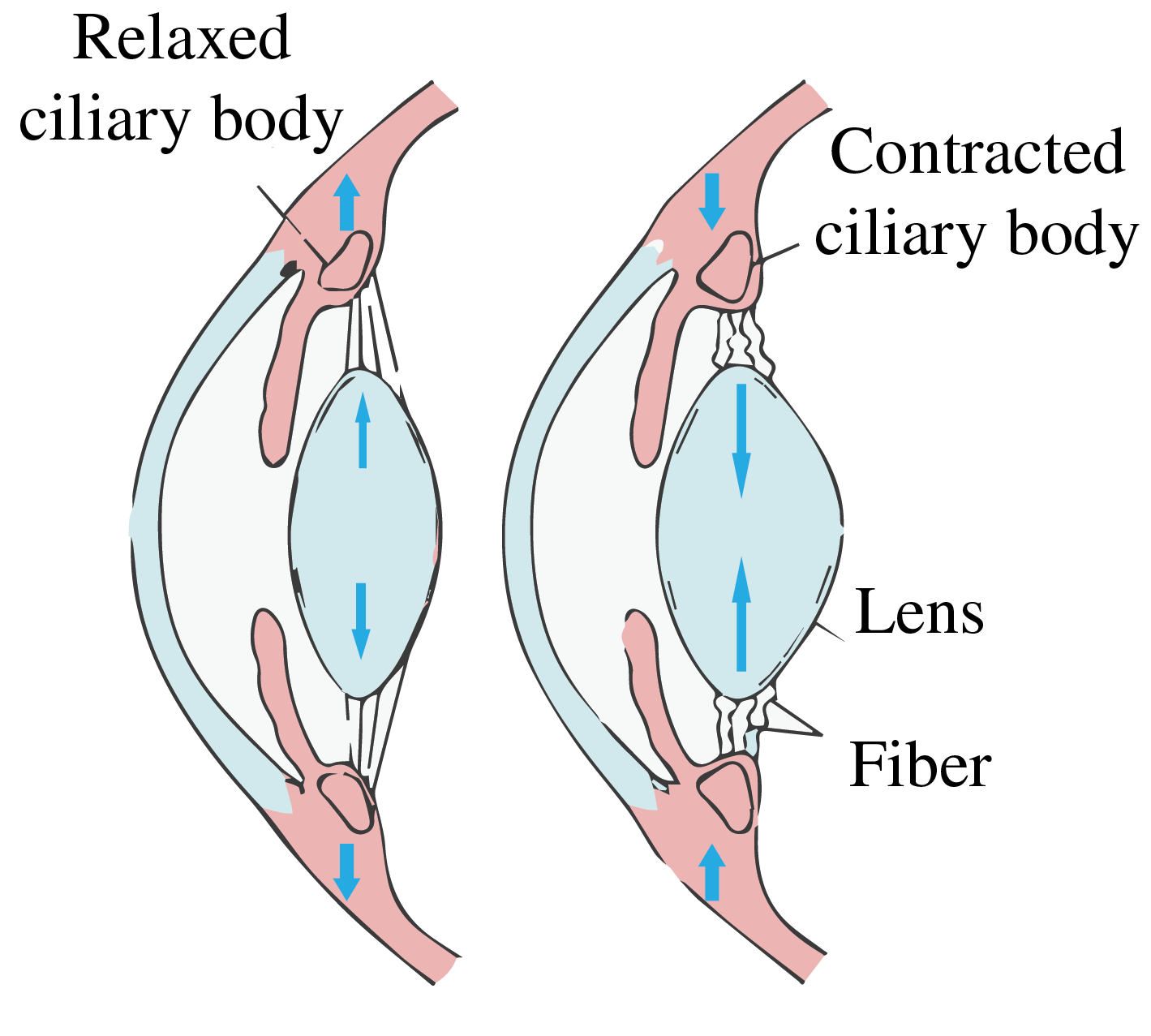

After passing the cornea, the rays reach the aqueous humour (\(n\approx\)1.336) with the iris or pupil. It can expand or contract from a 2 mm (bright sun) to 8 mm (low light) diameter to adapt to the light intensity. The iris gives colour to the eye. After the iris, the rays reach the flexible crystalline lens which has the size of a bean (9 mm in diameter, and 4 mm thick in relaxed condition). Its index of refraction varies from 1.406 in the centre to 1.386 at the edge.

Fig. 54 Left: Optical rays showing how an eye accommodates by changing its focal length. Right: Relaxed and contracted muscle at the crystalline lens needed for this accommodation.(Left: adapted from Wikimedia Commons Erin Silversmith / BY-NC-SA 2.5 Generic. Right: adapted from Sjaastad O.V., Sand O. and Hove K. (2010) Physiology of domestic animals, 2nd edn., Oslo: Scandinavian Veterinary Press).#

Working of the eye#

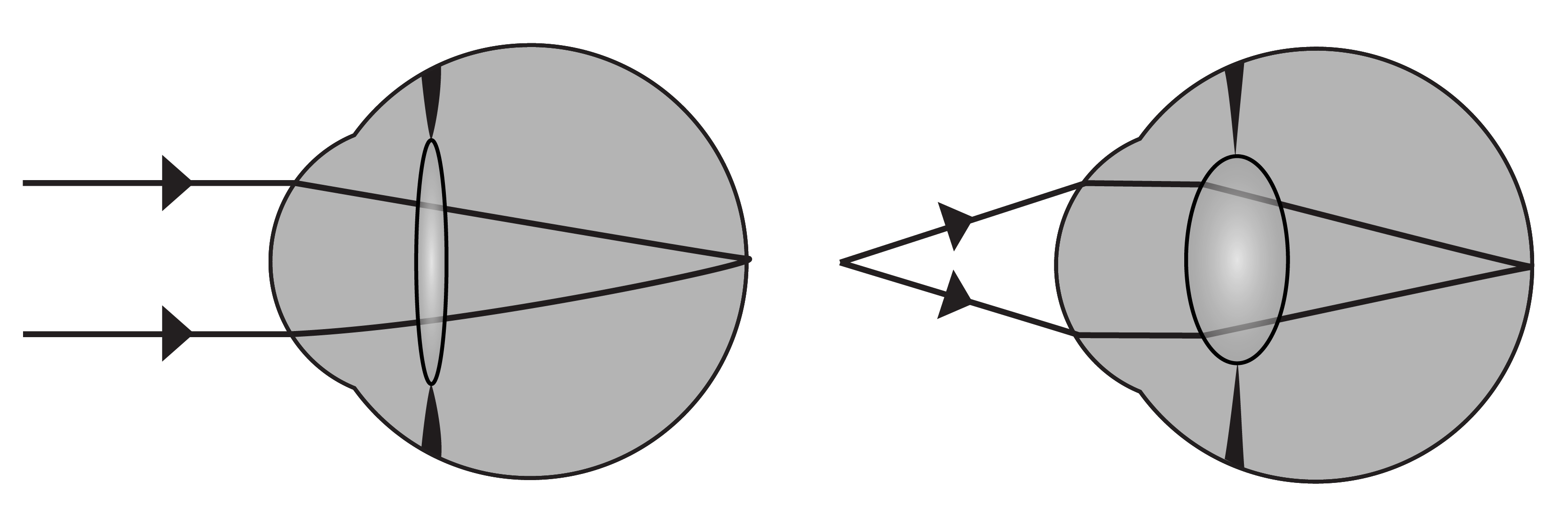

The entire eye can accurately be treated as two lenses in contact, of which the second lens can change its focal length. But often the system is approximated by only a single lens and this is also what we will do below. In relaxed condition, the object focal distance of the lens system is \(f_o=16\) mm as measured from the cornea while the image focal distance is equal to the length of the eye: \(f_i=24\) mm. These focal distances are different, because the refractive indices of the surrounding medium (air and vitreous humour) differ. The power of the healthy relaxed eye is according to (206), (210):

In relaxed condition the lens focuses light coming from infinity on the retina. When the object is closer, the eye muscles contract due to which the crystalline lens becomes more convex and the focal length of the system decreases, as seen on the right of Fig. 54. At a certain point, the object will be too close to be focused on the retina. This is called the near point of the eye. Due to the loss of elasticity of the muscle, the near point moves from 7 cm for teens to 100 cm for a 60-year-old. Fig. 54 shows the optical rays entering the eyes, for two configurations: an object at infinity and an object nearby. The normal near point is defined to be at the distance of 25 cm from the eye. The far point is the furthest object which is imaged on the retina by the relaxed eye. For a normal eye the far point is at infinity.

Retina#

The retina is composed of approximately 125 million photoreceptor cells: the rods and the cones. The rods are highly sensitive black and white (intensity) sensors, while the cones are colour sensitive for the wavelengths 390 nm - 780 nm. UV light is absorbed by the lens (people whose lens is removed because of cataract can “see” UV light). The fovea centralis is the most sensitive centre of the retina with a high density of cones. The eyes move continuously to focus the image on this area. The information is transferred by the optical nerve, placed at the back of the eye, where it causes a blind spot.

Dioptric Power of a lens#

For a single lens the dioptric power is defined by:

with \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) the radii of the thin lens measured in meter, \(n_l\) is the index of refraction of the lens and \(n_m\) that of the ambient medium. (When the media to the left and right of the lens are different, the refractive index to the right of lens and the right focal distance should be taken). For two lenses in contact, the focal length is given by:

hence the combined power of the two lenses in contact is the sum of the individual powers:

A positive lens of focal length \(f_1\)=10 cm air has a dioptric power \(\mathfrak{D_1}=10\) diopter. If it is in contact with a negative lens of dioptric power \(\mathfrak{D_2}=-10\) diopter, the resulting power is \(\mathfrak{D}=0\), equivalent to a parallel sheet of glass.

Eyeglasses#

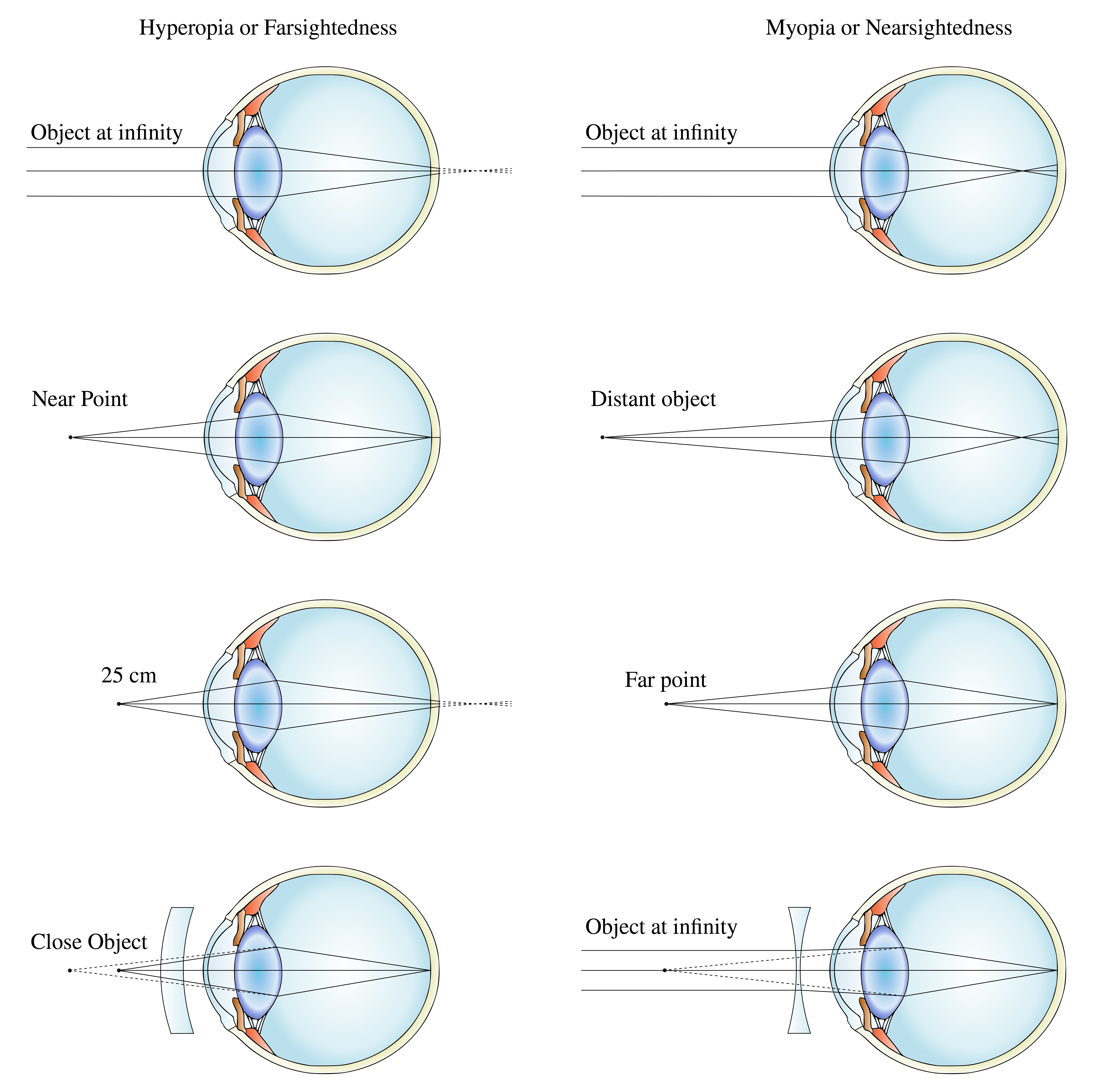

The eye can suffer from imperfections as seen in Fig. 55. We discuss the most common imperfections and their solutions.

a. Myopia or nearsightedness. A myopic eye has too short focal distances (has too high power). Distant objects are focused in front of the retina by the relaxed eye. The far point is thus not at infinity, but closer. This can be corrected by a negative lens. Suppose the far point is at 2 m. If the concave lens makes a virtual image of a distant object at distance 2 m in front of the cornea, the relaxed eye can see it clearly. The lens Law (215), with \(s_o=-\infty\) implies then \(f_i=s_i= -2\) m. Hence the required power of the lens is:

The lens is best put in the front focal plane of the relaxed eye, i.e. at approximately 16 mm in front of the cornea. This follows from (215) and the fact that the distance of the retina to the eye lens is roughly 22 mm while the refractive index of the vitrous humor is 1.337. Hence, the focal distance in air of the relaxed eye of \(22/1.337 \approx 16 \text{ mm}\). The reason for putting the lens at the focal distance is that in this case the magnification of the eye and the negative lens together are the same as for the uncorrected eye. To see this, draw a ray from the top of the object through the centre of the negative lens. This will then be made parallel to the optical axis by the eye lens; the distance of this ray to the optical axis is the image size on the retina. This ray will end up at the same point of the retina as when the negative lens is taken out, because it is not refracted by this lens.

Contact lenses are very close to the eye lens and hence the total power of the eye with a contact lens is simply the sum of the power of the eye and the contact lens.

b. Hyperopia or farsightedness. In this case a distant object is imaged by the relaxed eye behind the retina, i.e. the back focal distance of the relaxed eye is larger than the depth of the eye. Close objects can not be imaged on the retina, hence the near point is relatively far from the cornea. In order to bend the rays more, a positive lens is placed in front of the eye. Suppose that a hyperopic eye has near point at distance 125 cm. For an object at the normal near point \(s_o=-25\) cm to have virtual image at \(s_i=-125\) cm, so that it can be seen, the focal length of the positive lens must satisfy

hence the power must be \(\mathfrak{D}=1/f=+3.2\) diopter.

Fig. 55 Correction of farsighted (left) and nearsighted (right) eye (adapted from Wikimedia Commons by Gumenyuk I.S. / CC BY-SA 4.0).#

c. Presbyopia. This is the lack of accommodation of the eye as is common in people over 40. It results in an increase in the distance between the near point and the cornea. This defect affects all images. Presbyopia is usually corrected by glasses with progressive correction, the upper part of glass used for distance vision and the lower part for near vision.

d. Astigmatism. In this case the focal distances for two directions perpendicular to the optical axis are different. It is attributed to a lack of symmetry of revolution of the cornea. This is compensated by using glasses which themselves are astigmatic.

New Correction Technique#

In recent years, to correct eye defects such as myopia and astigmatism, technology has been developed to change the local curvatures of the surface of the cornea using an excimer laser. The laser is computer-controlled and causes photo-ablation in parts of the cornea.

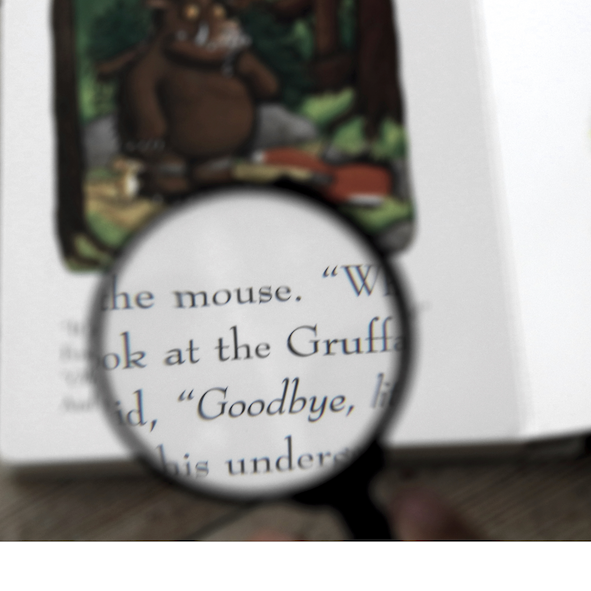

Magnifying Glasses#

A magnifying glass causes an image on the retina which is larger than without the magnifier. In principle, the image on the retina can be increased by simply bringing the object closer to the eye (reduce \(|s_o|\) at fixed \(s_i\)). But \(|s_o|\) can not be smaller than the near point \(d_o\), which we take here to be 25 cm. It is desirable to use a lens that makes a magnified erect image at a distance to the eye greater than \(d_o\). This can be achieved by a positive lens with the object closer to the lens than the first focal point, thereby producing a magnified virtual image. An example is given in Fig. 56.

Fig. 56 Example of a positive lens used as a magnifying glass (picture taken by A.J.L. Adam / CC-BY-SA 4.0).#

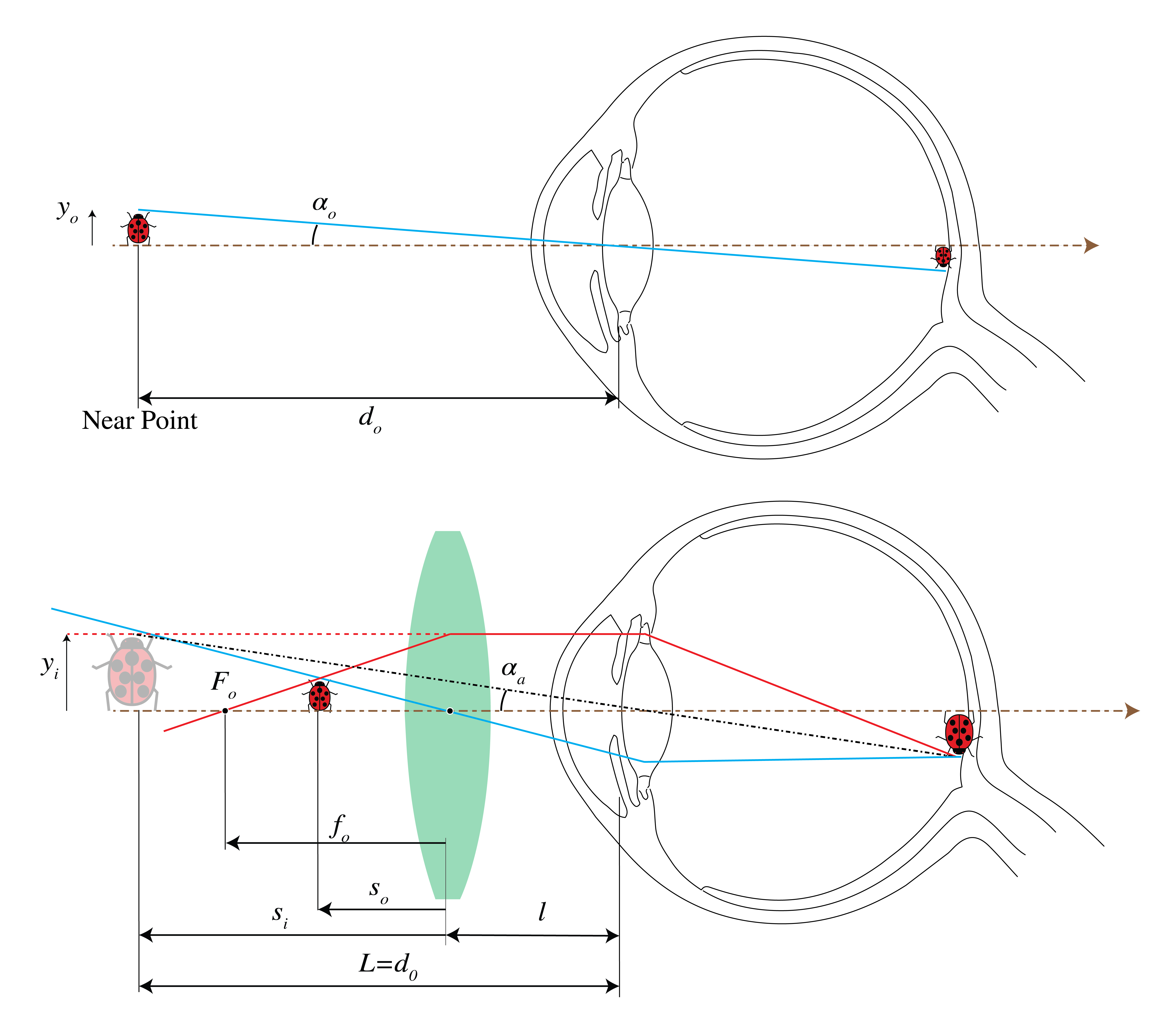

Magnifying Power#

The magnifying power \(\text{MP}\) or angular magnification \(M_a\) is defined as the ratio of the size of the retinal image obtained with the instrument and the size of the retinal image as seen by the unaided eye at normal viewing distance \(d_o\). To estimate the size of the retinal image, we compare in both cases where the chief ray through the top of the object and the centre of the pupil of the eye hits the retina. Since the distance between the eye lens and the retina is fixed, the ratio of the image size on the retina for the eye with and without magnifying glass is:

where \(\alpha_a\) and \(\alpha_u\) are the angles between the optical axis and the chief rays for the aided and the unaided eye, respectively, as shown in Fig. 57. Working with these angles instead of distances is in particular useful when the virtual image of the magnifying glass is at infinity. Using \(\alpha_a\approx y_i/L\) and \(\alpha_u\approx y_0/d_0\) with \(y_i\) and \(y_0\) positive and \(L\) the positive distance from the image to the eye (with as requirement : \(L\geq d_o\)), we find

Since \(s_i<0\) and \(f_o<0\) we have,

where we used the lens equation for the magnifying glass. We have \(s_i = -|s_i|=-(L-\mathcal{l})\), where \(\mathcal{l}\) is the distance between the magnifying glass and the eye. Hence, (257) becomes:

where \({\cal P}\) is the power of the magnifying glass.

Fig. 57 An unaided view (top) and an aided view using a magnifier.#

We distinguish three situations:

\(\mathcal{l}=|f_o|\): the magnifying power is then \(\text{MP}=d_0{\cal P}\).

\(\mathcal{l}=0\): hence \(L=d_0\) is smallest while \(\text{MP}\) is maximum:

The object is at the focal point of the magnifier (\(s_0=f_o\)), so that the virtual image is at infinity (\(L=\infty\)) and hence

for every distance \(\mathcal{l}\) between the eye and the magnifying glass. The rays are parallel, so that the eye views the object in a relaxed way. This is the most common use of the magnifier.

In practice \(d_0 {\cal P}=d_o/|f_o|\) is much larger than 1, so that \(\text{MP}\) is similar in the three cases.

Nomenclature#

Normally magnifiers are expressed in terms of the magnifying power when \(L=\infty\) (case 3 above). For example, a magnifier with a power of 10 Diopter has a \(\text{MP}\) equal to 2.5 or \(2.5\times\). In other words, the image is 2.5 times larger than it would be if the object would be at the near point of the unaided eye.

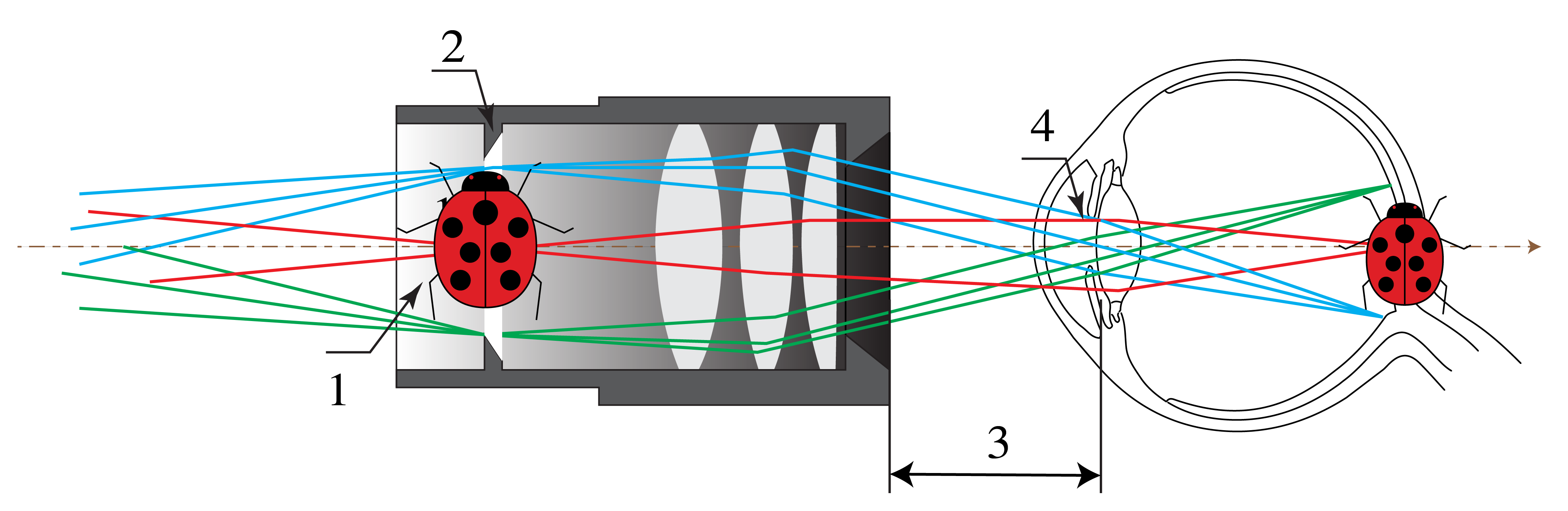

Eyepieces#

An eyepiece or ocular is a magnifier used before the eye at the end of an other optical instrument such as a microscope or a telescope. The eye looks into the ocular and the ocular “looks” into the optical instrument. The ocular provides a magnified virtual image of the image produced by the optical instrument. Similar to the magnifying glass, the virtual image should preferably be at or near infinity to be viewed by a relaxed eye. Several types of eye pieces exist and most of them are made out of two lenses:

the field lens, which is the first lens in the ocular;

the eye-lens, which is closest to the eye at a fixed distance called the eye relief. The aperture of the eyepiece is controlled by a field stop. An example is given in Fig. 58.

Fig. 58 Example of an eyepiece consisting of three lenses. 1) Real image, 2) field diaphragm, 3) eye relief, 4) eye pupil (adapted from Wikimedia Commons by Tamas-flex / CC BY-SA 3.0).#

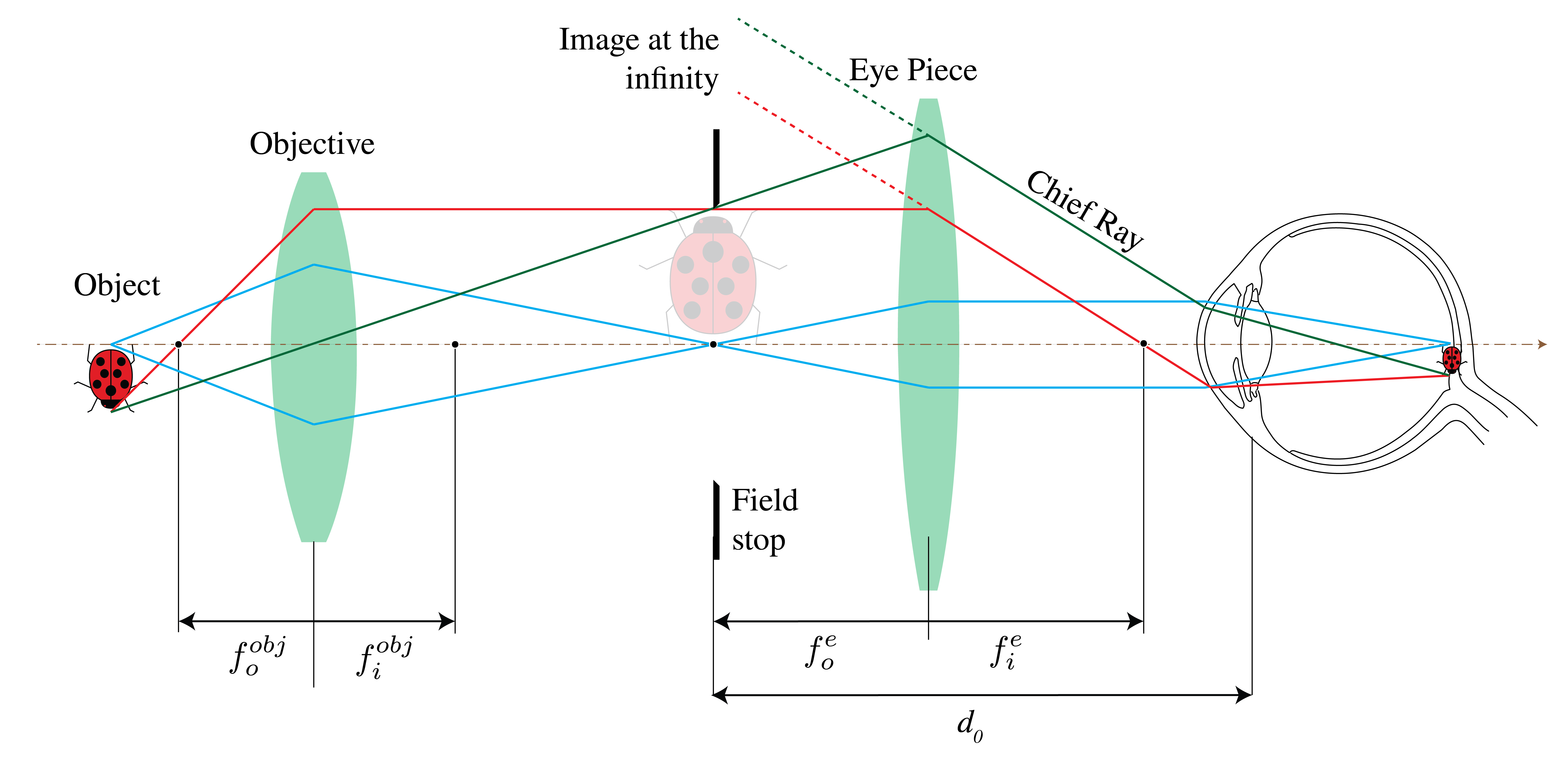

The Compound Microscope#

A magnifier alone can provide very high magnification only at the cost of intolerable aberrations. The compound microscope is a magnifier of close objects with a high angular magnification, generally more than \(30\times\). It was invented by Zacharias Janssen in Middelburg in 1590 (but this claim is disputed). The first element of the compound microscope is an objective (in Fig. 59 a simple positive lens) which makes a real, inverted and magnified image of the object in the front focal plane of an eyepiece (where there is also the field stop). The eyepiece will make a virtual image at infinity, as explained above.

Fig. 59 Simple compound microscope. The objective forms a real image of a nearby object. The eyepiece enlarges this intermediate image. The final image can be bigger than the barrel of the device, since it is virtual.#

The magnifying power of the entire system is the product of the transverse linear magnification of the objective \(M_{T}\) and the angular magnification of the eyepiece \(M_{Ae}\):

According to (221): \(M_{T}=\mathbin{-} x_i/f_i^{obj}\), where \(x_i\) is the distance of the image made by the objective to its back focal plane with focal distance \(f_i^{obj}\). We have \(x_i=L\) which is the tube length, i.e. the distance between the second focal point of the objective and the first focal point of the eyepiece. The tube length is standardised at 16 cm. Furthermore, according to (259), the angular magnification is for a virtual image at infinity is : \(M_{Ae}=d_o/f_i^e\). Hence, we obtain:

with the standard near-point \(d_o=\)25 cm. As an example, an Amici objective gives \(40 \times\) and combined with a \(10\times\) eye piece one gets \(MP=400\).

The numerical aperture of a microscope is a measure of the capability to gather light from the object. It is defined by:

with \(n_{im}\) the refractive index of the immersing medium, usually air, but it could be water or oil, and \(\theta_{max}\) the half-angle of the maximum cone of light accepted by the lens. The numerical aperture is the second number etched in the barrel of the objective. It ranges from 0.07 (low-power objectives) to 1.4 for high-power objectives. Note that it depends on the object distance. In Chapter 7 it will be explained that \(\text{NA}\) is, for a given object distance, proportional to the resolving power which is the minimum transverse distance between two object points that can be resolved in the image.

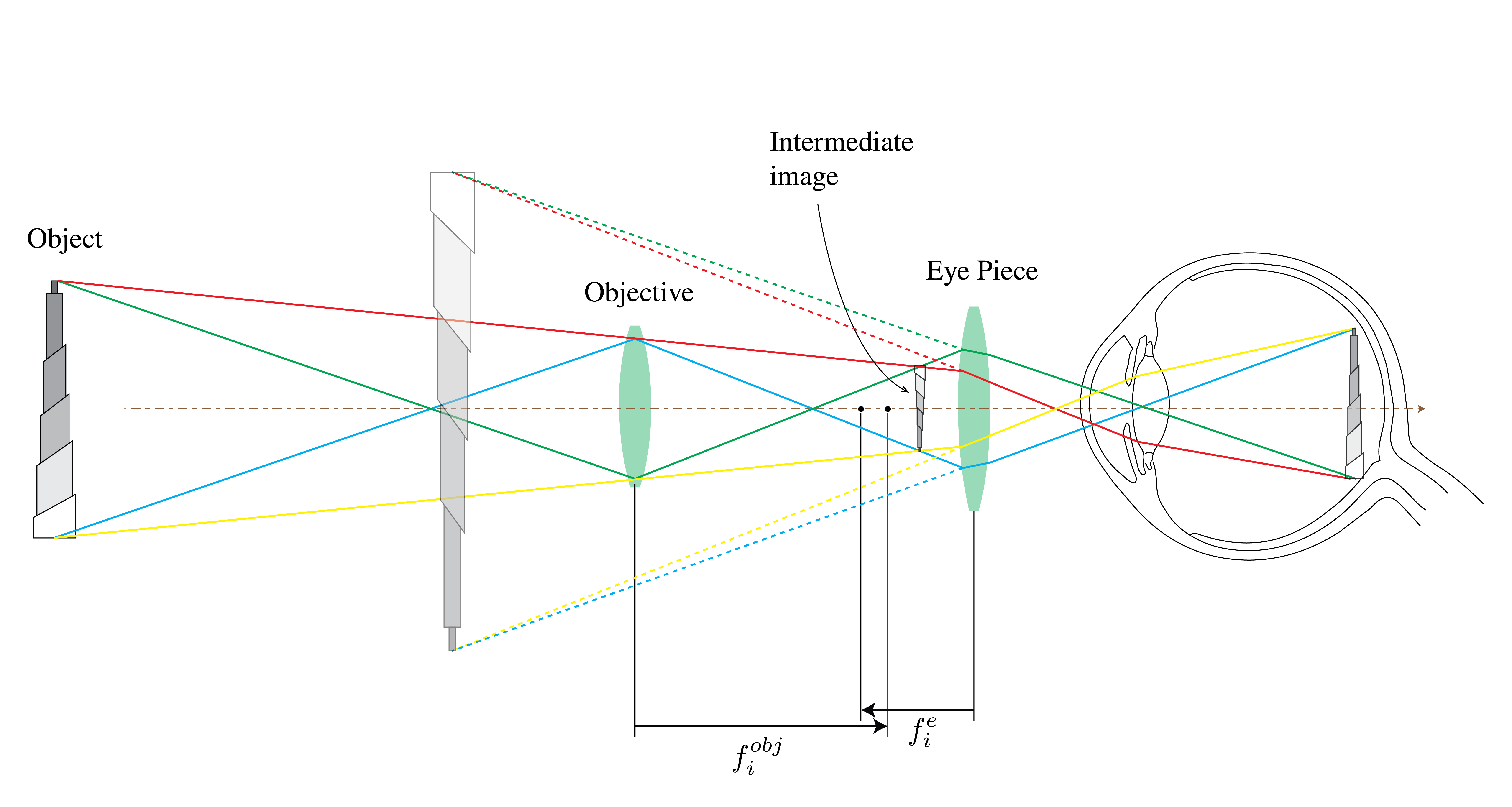

The Telescope#

A telescope enlarges the retinal image of a distant object. Like a compound microscope, it is also composed of an objective and an eyepiece as seen in Fig. 60.

Fig. 60 Keplerian astronomical telescope.#

The object in this figure is at a large but finite distance; therefore, an image is formed by the objective just after its second focal point. The eyepiece makes a virtual magnified image, to be viewed with a relaxed eye. Therefore, the intermediary image of the objective must be within the focal length \(f_i^e\) from the eyepiece. The final image is inverted.

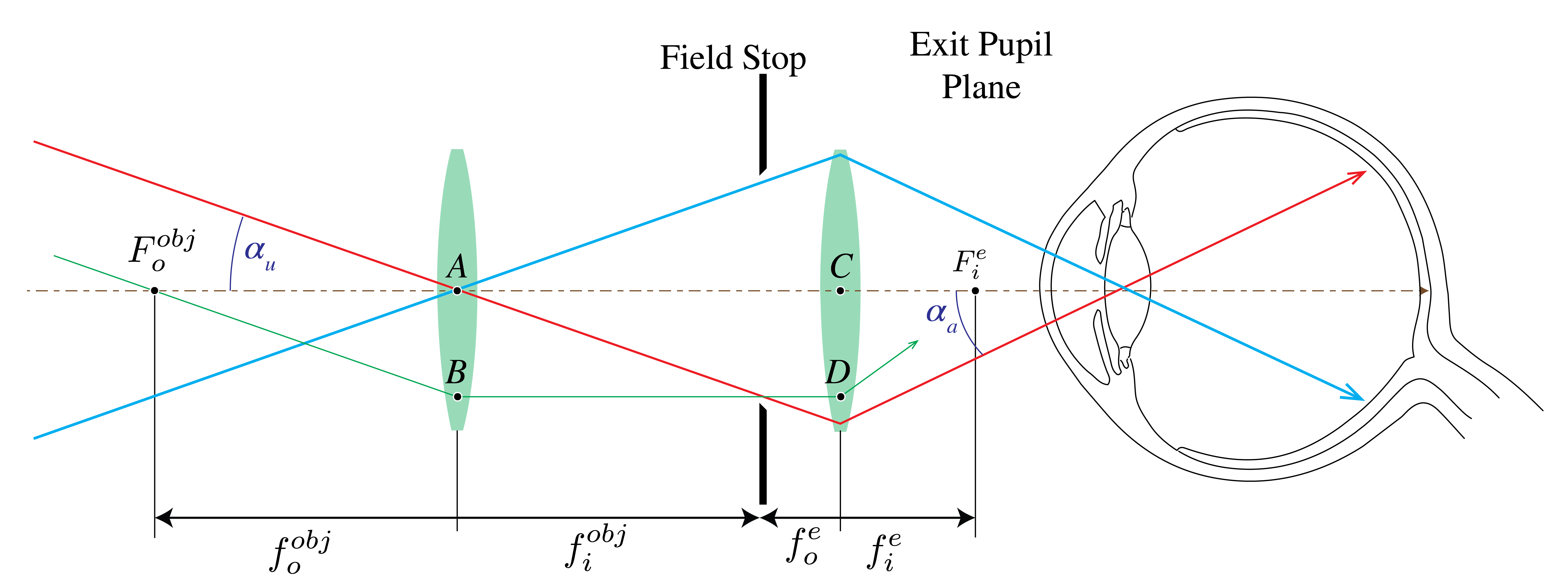

As seen earlier, the angular magnification is: \(\text{MP} = \alpha_a/\alpha_u\) where \(\alpha_u\) is the half angle of the cone of light that would be collected without telescope and \(\alpha_a\) is the half angle of the apparent cone of rays coming from the virtual image of the eye piece. For an object at infinity we find considering the triangles \(F_{o}^{obj}AB\) and \(F_i^{e}CD\) in Fig. 61 that

(The minus sign is because the image is inverted).

Fig. 61 Ray angles for a telescope#