Basic Electromagnetic and Wave Optics#

Maxwell’s equations provide a very complete description of light which includes diffraction, interference and polarisation. Yet it is strictly speaking not fully accurate, because it allows monochromatic electromagnetic waves to carry any amount of energy, whereas according to quantum optics the energy is quantised. According to quantum optics, light is a flow of massless particles, the photons, which each carry an extremely small quantum of energy: \(\hbar\omega\), where \(\hbar = 6.63 \times 10^{-34}/(2\pi)\) Js and \(\omega\) is the frequency, which for visible light is of the order \(5 \times 10^{14}\) Hz. Hence for visible light \(\hbar\omega \approx 3.3\times {10^{-19}}\) J.

Quantum optics is only important in experiments involving a small number of photons, i.e. at very low light intensities and for specially prepared photons states (e.g. entangled states) for which there is no classical description. In almost all applications of optics the light sources emit so many photons that quantum effects are irrelevant see Table 1.

Light Source |

Number of photons/s.m\(^2\) |

|---|---|

Laserbeam (10m W, He-Ne, focused to 20 \(\mu\)m) |

\(10^{26}\) |

Laserbeam (1 mW, He-Ne) |

\(10^{21}\) |

Bright sunlight on earth |

\(10^{18}\) |

Indoor light level |

\(10^{16}\) |

Twilight |

\(10^{14}\) |

Moonlight on earth |

\(10^{12}\) |

Starlight on earth |

\(10^{10}\) |

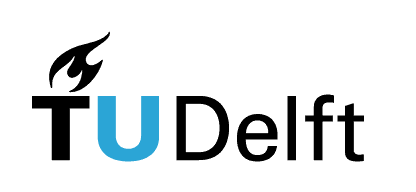

The visible part is only a small part of the overall electromagnetic spectrum (see Fig. 1). The results we will derive are however generally valid for electromagnetic waves of any frequency.

Fig. 1 The electromagnetic spectrum. (from Wikimedia Commons by NASA/ CC BY-SA ).#

The Maxwell Equations in Vacuum#

In a vacuum, light is described by vector fields \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}(\mathbf{r},t)\) [Volt/m][1] and \(\mathbf{\mathcal{B}}(\mathbf{r},t)\) [Tesla=Weber/\(\text{m}^2\)=g/(C.s)], which vary extremely rapidly with the position vector \(\mathbf{r}\) and time \(t\). These vector fields are traditionally called the electric field strength and the magnetic induction, respectively, and together they are referred to as “the electromagnetic field”. This terminology is explained by the fact that, because in optics these fields vary with time, the electric and magnetic fields always occur together, i.e. one does not exist without the other. Only when the fields are independent of time, there can be an electric field without a magnetic field and conversely. The first case is called electrostatics, the second magnetostatics. Time-dependent electromagnetic fields are generated by moving electric charges, the so-called sources. Let the source have charge density \(\rho(\mathbf{r},t)\) [C/\(\text{m}^3\)] and current density \(\mathbf{\mathcal{J}}(\mathbf{r},t)\) [C/(s.\(\text{m}^2\)]. Since charge can not be created nor destroyed, the rate of increase of charge inside a volume \(V\) must be equal to the flux of charges passing through its surface \(S\) from the outside to the inside of \(V\), i.e.:

where \(\hat{\mathbf{n}}\) is the outward-pointing unit normal on \(S\). Using the Gauss divergence (515), the left-hand side of (1) can be converted to a volume integral from which follows the differential form of the law of conservation of charge:

At every point in space and at every time, the field vectors satisfy the Maxwell equations[2]\(^{, }\)[3]:

where \(\epsilon_0= 8.8544 \times 10^{-12}\) C \(^2\)N\(^{-1}\)m\(^{-2}\) is the dielectric permittivity and \(\mu_0 = 1.2566 \times 10^{-6} \text{m kg C}^{-2}\) is the magnetic permeability of vacuum. The quantity \(c=(1/\epsilon_0\mu_0)^{1/2}=2.997924562 \times 10^{8} \pm 1.1\) m/s is the speed of light in vacuum and \(Z=\sqrt{\mu_0/\epsilon_0}=377\Omega =377\) Vs/C is the impedance of vacuum.

Atoms are neutral and consist of a positively charged kernel surrounded by a negatively charged electron cloud. In an electric field, the centres of charge of the positive and negative charges get displaced with respect to each other. Therefore, an atom in an electric field behaves like an electric dipole. In polar molecules, the centres of charge of the positive and negative charges are permanently separated, even without an electric field. But without an electric field, they are randomly orientated and therefore have no net effect, while in the presence of an electric field they line up parallel to the field. Whatever the precise mechanism, an electric field induces a certain net dipole moment density per unit volume \(\mathbf{\mathcal{P}}(\mathbf{r})\) [C/\(\text{m}^2\)] in matter which is proportional to the local electric field \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}(\mathbf{r})\):

where \(\chi_e\) is a dimensionless quantity, the electric susceptibility of the material. A dipole moment which varies with time radiates an electromagneticc field. It is important to realize that in (7) \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}\) is the total local electric field at the position of the dipole, i.e. it contains the contribution of all other dipoles, which are also excited and radiate an electromagnetic field themselves. Only in the case of diluted gasses, the influence of the other dipoles in matter can be neglected and the local electric field is simply given by the field emitted by a source external to the matter under consideration.

A dipole moment density that changes with time corresponds to a current density \(\mathbf{\mathcal{J}}_p\) [Ampere/\(\text{m}^2\)=C/(\(\text{m}^2\) s)] and a charge density \(\varrho_p\) [C/\(\text{m}^3\)] given by

All materials conduct electrons to a certain extent, although the conductivity \(\sigma\) [Ampere/(Volt m)=C/(Volt s] differs greatly between dielectrics, semi-conductors and metals (the conductivity of copper is \(10^7\) times that of a good conductor such as sea water and \(10^{19}\) times that of glass). The current density \(\mathbf{\mathcal{J}}_c\) and the charge density corresponding to the conduction electrons satisfy:

where (10) is Ohm’s Law. The total current density on the right-hand side of Maxwell’s Law (4) is the sum of \(\mathbf{\mathcal{J}}_p\), \(\mathbf{\mathcal{J}}_c\) and an external current density \(\mathbf{\mathcal{J}}_{ext}\), which we assume to be known. Similarly, the total charge density at the right of (5) is the sum of \(\varrho_p\), \(\varrho_c\) and a given external charge density \(\varrho_{ext}\). The latter is linked to the external current density by the law of conservation of charge (2). Hence, (4) and (5) become

We define the permittivity \(\epsilon\) in matter by

Then (12) and (13) can be written as

It is verified in Problem 1 that in a conductor any accumulation of charge is extremely quickly reduced to zero. Therefore we may assume that

If the material is magnetic, the magnetic permeability is different from vacuum and is written as \(\mu=\mu_0(1+\chi_m)\), where \(\chi_m\) is the magnetic susceptibility. In the Maxwell equations, one should then replace \(\mu_0\) by \(\mu\). However, at optical frequencies magnetic effects are negligible (except in ferromagnetic materials, which are rare). We will therefore always assume that the magnetic permeability is that of vacuum: \(\mu=\mu_0\).

It is customary to define the magnetic field by \(\mathbf{\mathcal{H}}=\mathbf{\mathcal{B}}/\mu_0\) [Ampere/m=C/(ms)]. By using the magnetic field \(\mathbf{\mathcal{H}}\) instead of the magnetic induction \(\mathbf{\mathcal{B}}\), Maxwell’s equations become more symmetric:

This is the form in which we will be using the Maxwell equations in matter in this book. It is seen that the Maxwell equations in matter are identical to those in vacuum, with \(\epsilon\) substituted for \(\epsilon_0\).

We end this section with remarking that our derivations are valid for non-magnetic materials which are electrically isotropic. This means that the magnetic permeability is that of vacuum and that the permittivity \(\epsilon\) is a scalar. In an anisotropic dielectric the induced dipole vectors are in general not parallel to the local electric field. Then \(\chi_e\) and therefore also \(\epsilon\) become matrices. Throughout this book all matter is assumed to be non-magnetic and electrically isotropic.

We consider a homogeneous insulator (i.e. \(\epsilon\) is independent of position and \(\sigma\)=0) in which there are no external sources:

In optics the external source, e.g. a laser, is normally spatially separated from the objects of interest with which the light interacts. Therefore the assumption that the external source vanishes in the region of interest is often justified. Take the curl of (18) and the time derivative of (19) and add the equations obtained. This gives

Now for any vector field \(\mathbf{\mathcal{A}}\) there holds:

where \(\mathbf{\nabla}^2 \mathbf{\mathcal{A}}\) is the vector:

with

Because Gauss’s law (20) with \(\varrho_{ext}=0\) and \(\epsilon\) constant implies that \(\mathbf{\nabla}\cdot \mathbf{\mathcal{E}}=0\), (24) applied to \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}\) yields

Hence, (23) becomes

By a similar derivation it is found that also \(\mathbf{\mathcal{H}}\) satisfies (28). Hence in a homogeneous dielectric without external sources, every component of the electromagnetic field satisfies the scalar wave equation:

The refractive index is the dimensionless quantity defined by

The scalar wave equation can then be written as

The speed of light in matter is

Time-Harmonic Solutions of the Wave Equation#

The fact that, in the frequently occurring circumstance in which light interacts with a homogeneous dielectric, all components of the electromagnetic field satisfy the scalar wave equation, justifies the study of solutions of this equation. Since in most cases in optics monochromatic fields are considered, we will focus our attention on time-harmonic solutions of the wave equation.

Time-Harmonic Plane Waves#

Time-harmonic solutions depend on time by a cosine or a sine function. One can easily verify by substitution that

where \({\cal A}>0\) and \(\varphi\) are constants, is a solution of (31), provided that

where \(k_0=\omega \sqrt{\epsilon_0 \mu_0}\) is the wave number in vacuum. The frequency \(\omega>0\) can be chosen arbitrarily. The wave number \(k\) in the material is then determined by (34). We define \(T=2\pi/\omega\) and \(\lambda=2\pi/k\) as the period and the wavelength in the material, respectively. Furthermore, \(\lambda_0=2\pi/k_0\) is the wavelength in vacuum.

Remark. With “the wavelength”, we always mean the wavelength in vacuum.

We can write (33) in the form

where \(c/n=1/\sqrt{\epsilon\mu_0}\) is the speed of light in the material. \({\cal A}\) is the amplitude and the argument under the cosine: \(k\left(x-\frac{c}{n} t\right)+\varphi\) is called the phase at position \(x\) and at time \(t\). A wave front is a set of space-time points where the phase is constant:

At any fixed time \(t\) the wave fronts are planes (in this case perpendicular to the \(x\)-axis), and therefore the wave is called a plane wave. As time proceeds, the wave fronts move with velocity \(c/n\) in the positive \(x\)-direction.

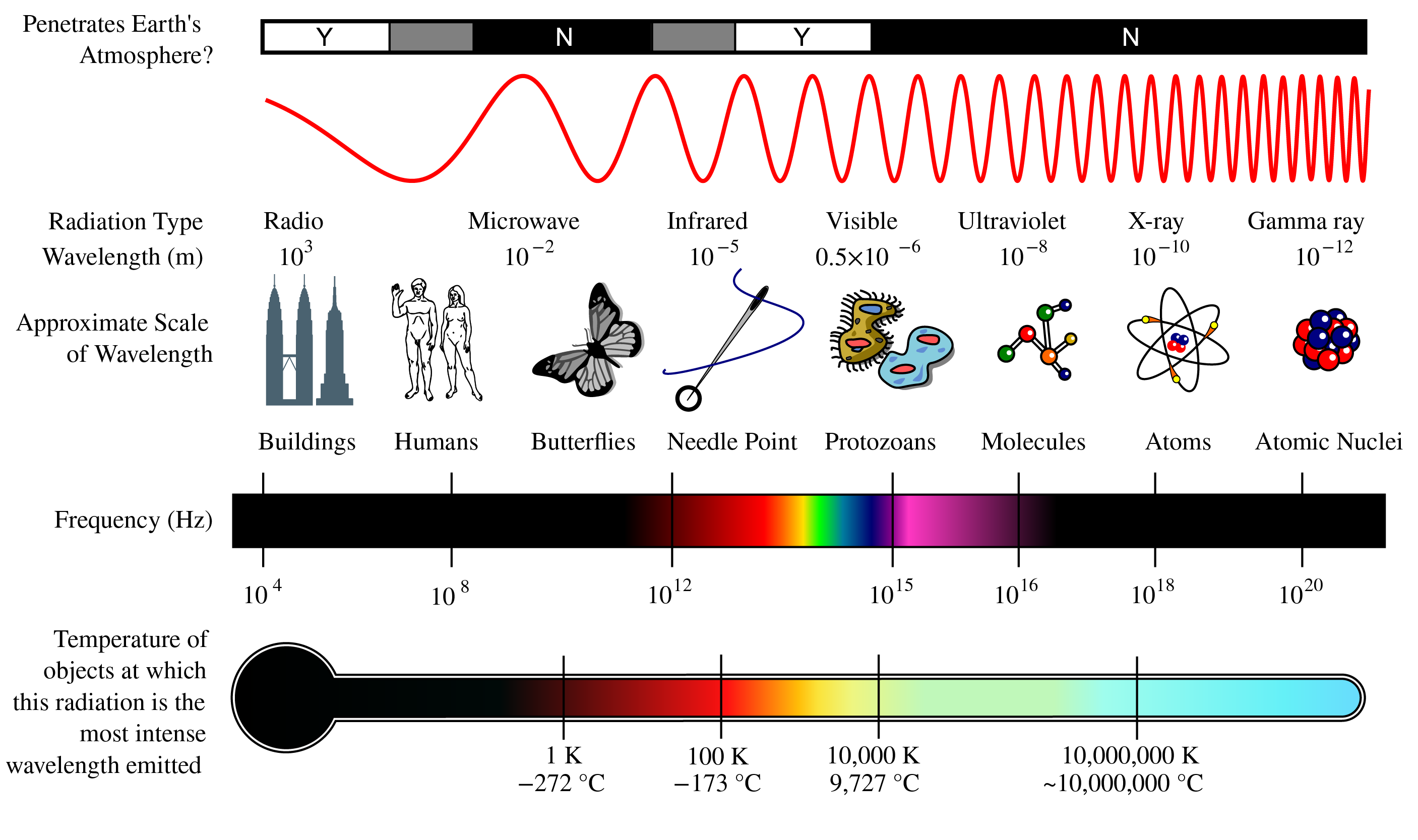

A time-harmonic plane wave propagating in an arbitrary direction is given by

where \({\cal A}\) and \(\varphi\) are again constants and \(\mathbf{k}=k_x\hat{\mathbf{x}}+k_y \hat{\mathbf{y}}+k_z \hat{\mathbf{z}}\) is the wave vector. The wave fronts are given by the set of all space-time points \((\mathbf{r}, t)\) for which the phase \(\mathbf{k}\cdot \mathbf{r} -\omega t + \varphi\) is constant, i.e. for which

At fixed times the wave fronts are planes perpendicular to the direction of \(\mathbf{k}\) as shown in Fig. 2. Eq. (36) is a solution of (31) provided that

The direction of the wave vector can be chosen arbitrarily, but its length is determined by the frequency \(\omega\).

Fig. 2 Planes of constant phase.#

We consider a general time-harmonic solution of the wave equation (29):

where the amplitude \({\cal A}(\mathbf{r})>0\) and the phase \(\varphi(\mathbf{r})\) are functions of position \(\mathbf{r}\). The wave fronts consist of sets of space-time points \((\mathbf{r},t)\) where the phase is equal to some constant:

At fixed time \(t\), the sets of constant phase: \(\varphi(\mathbf{r})=\omega t + \text{constant}\) are surfaces which in general are not planes, hence the solution in general is not a plane wave. Eq. (39) could for example be a wave with spherical wave fronts, as discussed below.

Remark. A plane wave is infinitely extended and transports an infinite amount of electromagnetic energy. A plane plane can therefore not exist in reality, but it is nevertheless a usual idealisation. As will be demonstrated in Section 7.1, every time-harmonic solution of the wave equation can always be expanded in terms of plane waves of the form (36).

For time-harmonic solutions it is often convenient to use complex notation. Define the complex amplitude by:

i.e. the modulus of the complex number \(U(\mathbf{r})\) is the amplitude \({\cal A}(\mathbf{r})\) and the argument of \(U(\mathbf{r})\) is the phase \(\varphi(\mathbf{r})\) at \(t=0\). The time-dependent part of the phase: \(-\omega t\) is thus separated from the space-dependent part of the phase. Then (39) can be written as

Hence \({\cal U}(\mathbf{r},t)\) is the real part of the complex time-harmonic function

Remark. The complex amplitude \(U(\mathbf{r})\) is also called the complex field. In the case of vector fields such as \(\mathbf{E}\) and \(\mathbf{H}\) we speak of complex vector fields, or simply complex fields. Complex amplitudes and complex (vector) fields are only functions of position \(\mathbf{r}\); the time dependent factor \(\exp(-i\omega t)\) is omitted. To get the physical meaningful real quantity, the complex amplitude or complex field first has to be multiplied by \(\exp(-i\omega t)\) and then the real part must be taken.

The following convention is used throughout this book:

Real-valued physical quantities (whether they are time-harmonic or have more general time dependence) are denoted by a calligraphic letter, e.g. \(\mathcal{U}\), \(\mathcal{E}_x\), or \(\mathcal{H}_x\). The symbols are bold when we are dealing with a vector, e.g. \(\mathbf{\mathcal{E}}\) or \(\mathbf{\mathcal{H}}\). The complex amplitude of a time-harmonic function is linked to the real physical quantity by (42) and is written as an ordinary letter such as \(U\) and \(\mathbf{E}\).

It is easier to calculate with complex amplitudes (complex fields) than with trigonometric functions (cosine and sine). As long as all the operations carried out on the functions are linear, the operations can be carried out on the complex quantities. To get the real-valued physical quantity of the result (i.e. the physical meaningful result), multiply the finally obtained complex amplitude by \(\exp(-i\omega t)\) and take the real part. The reason that this works is that taking the real part commutes with all linear operations, i.e. taking first the real part to get the real-valued physical quantity and then operating on this real physical quantity gives the same result as operating on the complex scalar and taking the real part at the end.

By substituting (42) into the wave equation (31) we get

Since this must vanish for all times \(t\), it follows that the complex expression between the brackets \(\{.\}\) must vanish. To see this, consider for example the two instances \(t=0\) and \(t=\pi/(2\omega\). We conclude that the complex amplitude satisfies

where \(k_0=\omega \sqrt{\epsilon_0 \mu_0}\) is the wave number in vacuum.

Remark. The complex quantity of which the real part has to be taken is: \(U\exp(-i\omega t)\). As explained above, it is not necessary to drag the time-dependent factor \(\exp(-i \omega t )\) along in the computations: it suffices to calculate only with the complex amplitude \(U\), then multiply by \(\exp(-i\omega t)\) and then take the real part. However, when a derivative with respect to time has to be taken: \(\partial /\partial t\), the complex field much be multiplied by \(-i\omega\). This is also done in the time-harmonic Maxwell’s equations in Time-Harmonic Maxwell Equations in Matter below.

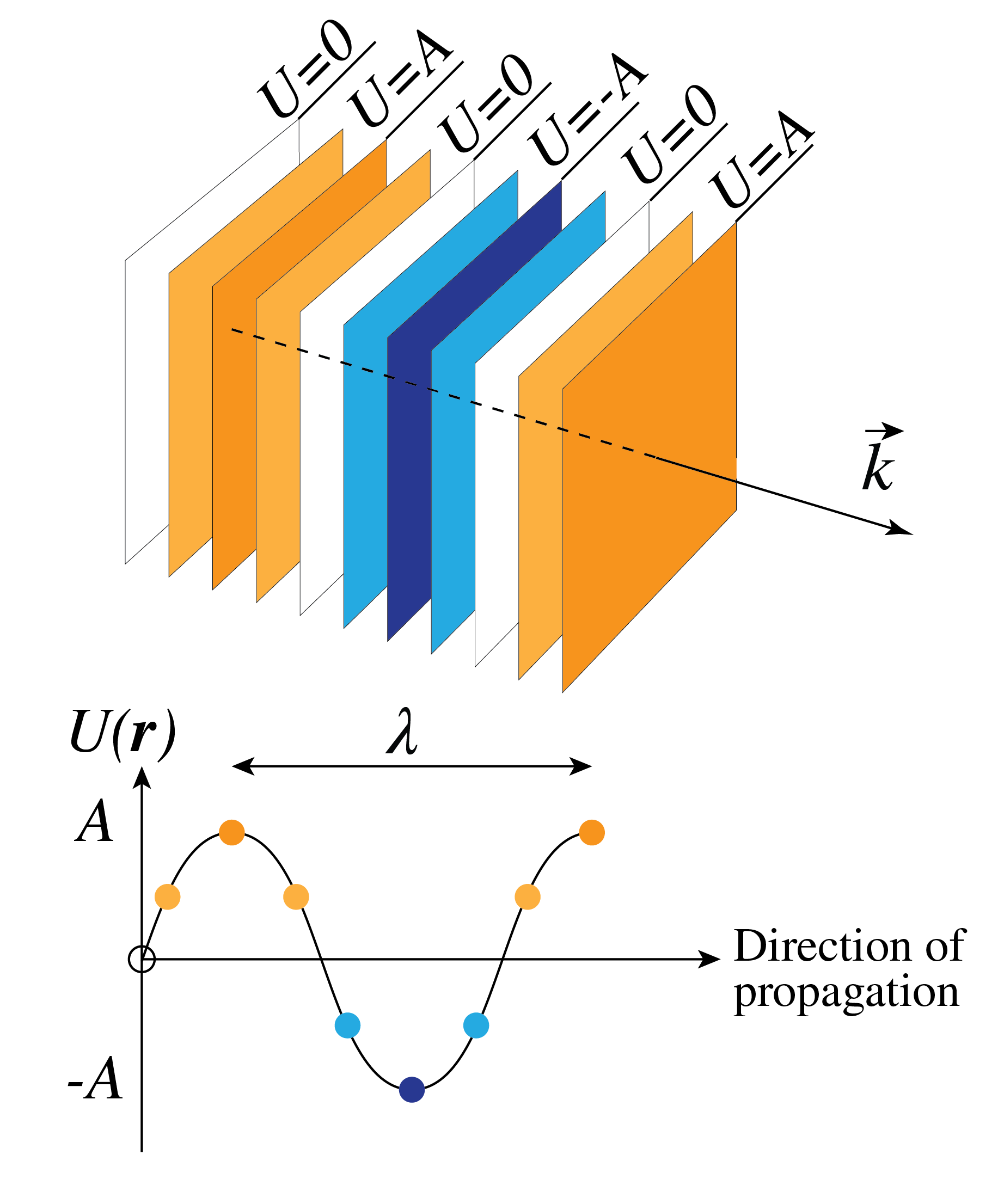

Time-Harmonic Spherical Waves#

A spherical wave depends on position only by the distance to a fixed point. For simplicity we choose the origin of our coordinate system at this point. We thus seek a solution of the form \({\cal U}(r,t)\) with \(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}\). For spherical symmetric functions we have

It is easy to see that outside of the origin

satisfies (46) for any choice for the function \(f\), where as before \(c=1/\sqrt{\epsilon_0\mu_0}\) is the speed of light and \(n=\sqrt{\epsilon/\epsilon_0}\). Of particular interest are time-harmonic spherical waves:

where \({\cal A}\) is a constant

and \(\pm kr - \omega t +\varphi\) is the phase at \(\mathbf{r}\) and at time \(t\). A wave front is a set of space-time points \((\mathbf{r},t)\) where the phase is equal to a constant:

Wave fronts are thus spheres which move with the speed of light in the radial direction. When the \(+\) sign is chosen, the wave propagates outwards, i.e. away from the origin. The wave is then radiated by a source at the origin. Indeed, if the \(+\) sign holds in (48), then if time \(t\) increases, (50) implies that a surface of constant phase moves outwards. Similarly, if the \(-\) sign holds, the wave propagates towards the origin which then acts as a sink.

Fig. 3 Spherical wave fronts with amplitude decreasing with distance.#

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

from IPython.display import HTML

# Function to initialize the plot

def init():

im.set_data(wave(r, 0))

line1.set_ydata(wave(x, 0))

line2.set_ydata(np.flip(wave(x, 0)))

return [im, line1, line2]

# Function to update the plot for each frame

def update(frame):

im.set_array(wave(r, frame))

line1.set_ydata(wave1d(x, frame))

line2.set_ydata(np.flip(wave1d(x, frame)))

return [im, line1, line2]

def wave(r, t):

A = 1

k = 5

omega = 2*np.pi/total_frames

phi = 0

#return A*1/(r+eps)*np.cos(k*r - omega*t + phi)

return A*np.exp(-r/tau)*np.cos(k*r - omega*t + phi)

def wave1d(r,t):

A = ly

k = 5

tau = 2

omega = 2*np.pi/total_frames

phi = 0

return A*np.exp(-r/tau)*np.cos(k*r - omega*t + phi)

lx = 5

ly = 2.5

color = "dodgerblue"

lw = 0.3

tau = 2

total_frames = 60

eps = 1E-1

# Create a figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,5))

x = np.linspace(0, lx, 800)

xx = np.linspace(-lx, lx, 800)

yy = np.linspace(-ly, ly, 800)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(xx, yy)

r = np.sqrt(X**2 + Y**2)

im = ax.imshow(wave(r, 0), cmap='twilight', clim=[-ly, ly],extent=[xx.min(), xx.max(), yy.min(), yy.max()])

line1, = ax.plot(x, wave1d(x, 0), color=color)

line2, = ax.plot(x - lx, np.flip(wave1d(x, 0)), color=color)

line3, = ax.plot(x, ly*np.exp(-x/tau), "-.k", linewidth=lw)

line4, = ax.plot(x, -ly*np.exp(-x/tau), "-.k", linewidth=lw)

line5, = ax.plot(x - lx, np.flip(ly*np.exp(-x/tau)), "-.k", linewidth=lw)

line6, = ax.plot(x - lx, -np.flip(ly*np.exp(-x/tau)), "-.k", linewidth=lw)

ax.axis('off')

# Set up the animation

ani = FuncAnimation(fig, update, frames=range(total_frames), init_func=init, blit=True)

plt.close()

# Show the plot

HTML(ani.to_jshtml(fps=30))